What is referred to as the Agony in the Garden, is recounted by the synoptic writers, Matthew, Mark and Luke. The Holy Hour, part of life in many parishes, finds its origins in Jesus’ words, recounted by Matthew and Mark, to the sleepy-head, Peter: “Could you not watch with me an hour?” John, aware of the synoptic accounts, does not need to repeat what is contained in the earlier Gospels. The Agony in the Garden shows Jesus of Nazareth at his most human, at his most vulnerable.

Gospel

Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, is the Good News, the source and centre of each Gospel. The four Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, are each a particular expression of the Gospel (Good News) of Jesus of Nazareth, as are the other individual writings of the New Testament.

All this is consistent with the Gospels being the witness of the Apostles: Matthew, an Apostle, a witness to the Jews; Mark, drawing on the witness of St Peter, the first of the Apostles; Luke, drawing on the witness of St Peter (especially in Acts), and later the witness of St Paul; and, arguably much later, St John, as it were, plugging the gaps. The term “witness” is no casually selected word, but has its origin in the mandate of Jesus of Nazareth at the Ascension to be “my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judaea and Samaria and to the end of the earth”. A witness tells the truth, and so the mandate is to tell the truth revealed by Jesus of Nazareth.

Jewish Scriptures

This witness assumes the truth of the Jewish scriptures. For this reason, a Christian who dismisses what Christians call the Old Testament not only dismisses a priceless gift, but places him or herself at odds with New Testament teaching.

The intellectual perspective of the Gospel writers is summed up by Our Lord at the conclusion of the Gospel of Luke:

“These are my words which I spoke to you, while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms must be fulfilled…Thus it is written that the Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins should be preached in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are the witnesses of these things.”

Jesus of Nazareth is to be understood in the context of the Jewish scriptures.

Petrine Outlines

The Petrine outlines of Christian belief at the beginning of Acts are central to the whole tradition. The incarnation, birth, life, crucifixion, death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God, the fulfilment of the Hebrew scriptures, are central to the whole tradition.

These Petrine outlines of Christian belief echo down the ages in the Apostles’ Creed, and in the Nicene Creed. If one does not understand the Apostles’ Creed, if one does not understand the Nicene Creed, one does not understand what it is to be a Christian. The Catechism of the Catholic Church is simply a contemporary extension of the witness of St Peter following the Ascension.

New Testament

To my mind, the early writings of the New Testament, the letters of St Paul, provide a rather “abstract” analysis, from the perspective of a Jewish scholar, of what it means to be a Christian. The letters of St Paul are topical, dealing with a whole range of specific topics as to what it means to be a Christian. The synoptic Gospels, composed later in time than Paul’s letters, are a reflection which understand the person and life of Jesus of Nazareth to be central to the Gospel.

The writings of St John, including St John’s Gospel, the three Letters of StJohn, Apocalypse (or Revelation), arguably written well after the synoptic Gospels, are a yet morerefined theological elaboration than the earlier writings of the New Testament. In all this the early Church is engaged in intense theological reflection as to the person of Jesus of Nazareth, and as to the Church itself.

Good News

From the very beginning, even during the lifetime of Jesus of Nazareth, the Apostles were aware of the mandate to spread the Good News. This mandate to spread the Gospel was understood ever more clearly at the time of the Ascension. Ever more so after Pentecost. The Good News is summed up by St Paul to the Corinthians:

“For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, that he appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve.”

There are numerous such statements of Christian belief throughout the New Testament. From the beginning there was a concern to teach what was true, to avoid error.

Stephen

The account in Acts of the seven deacons, including Stephen, selected to serve the material needs of the Church, emphasises that the role of the Apostles demands devotion to prayer and the ministry of the word, rather than simply serving at tables. Stephen receives the imposition of hands from the Apostles, an illustration of the hierarchically organised community which existed from the beginning. From the prayer and ministry of the word of the hierarchically organised community, the New Testament, especially the Gospels, was to come. Stephen’s speech, prior to him being stoned to death, demonstrates that, while devoting himself to the material needs of the Christian community, he was also a person of prayer, well able to give an account of the faith.

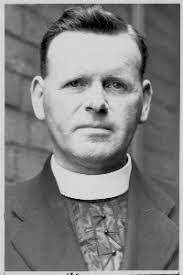

Fr Austin Woodbury SM comments:

“There existed a primitive kerygma, that is an oral preaching previous to the written gospels, and we can reconstruct it in part by consideration of determinate passages in the New Testament.”

Fr Austin Woodbury SM

Fr Austin Woodbury, a Marist priest, from 1945 to 1974, conducted the Aquinas Academy, then a centre of serious philosophical and theological study, located near St Patrick’s Church Hill. Woodbury was known to his students and friends as The Doc. Even today The Doc’s texts are worth reading. They are perennial. They will continue to be worth reading long into the future, long after the writings of his intellectual critics have been despatched to the scrap heap. The Doc’s texts, available on the internet, but unfortunately, not published in book form, deal comprehensively with many topics fundamental to the Catholic intellectual tradition including metaphysics, the existence and nature of God, philosophical anthropology, ethics, epistemology, logic, apologetics, grace, the last things, the Mass, the Sacraments, the Our Father, the Beatitudes, the writings of St Thomas Aquinas.

Thomistic Revival

The Doc accepted enthusiastically the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, albeit that the Council was influenced by the Ressourcement thinkers, significantly different in approach from that of Leonine Thomism exemplified by both Woodbury, and by his teacher, Fr Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange OP. Both Woodbury and Garrigou-Lagrange are to be regarded as part of the Thomistic revival inspired by Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris (1879). There will always be different theological approaches within the Church, theological approaches which, despite their differences, are entirely consistent with the Church’s Magisterium.

Tens of thousands of students, mainly laypersons, but some who were to become priests and religious, passed through the Aquinas Academy. A few went on to complete doctoral studies in Rome.

James Franklin

Some went on to distinguished academic careers in some secular subject. An example is Professor James Franklin who spent an adult lifetime at the University of New South Wales as a mathematician. In “retirement” Professor Franklin has written serious history and philosophy including Corrupting the Youth: a History of Philosophy in Australia (2003), Catholic Values and Australian Realities (2006); The Worth of Persons: the Foundations of Ethics (2022); Catholic Thought and Catholic Action: Scenes from Australian Catholic Life (2023).

For most of The Doc’s students, even though they did not become priests or religious, or go on to further study in Rome, or elsewhere, their personal, family and professional lives were greatly enriched by their study at the Aquinas Academy.

St Patrick’s Church Hill

St Patrick’s Church Hill, during the Woodbury years, was conducted by the MaristFathers. Responsibility for St Patrick’s, and for its original largely Irish Australian parishioners, was assumed in 1868 by the then French Marist priests. Unfortunately, in 2025, the Marists, no longer having the vocations of a different era, will be departing. St Patrick’s Church Hill will nevertheless continue.

Mass and Confessions

St Patrick’s Church Hill has been known for the number of its daily Masses, and for the almostcontinual availability of confessions. One could always go to Confession at St Pat’s, anonymously. For busy workers, Mass has always been available at numerous convenient times, not only on Sundays but throughout the week.

Fr Aloysius Van Houte

From 1954 to 1990 Fr Aloysius Van Houte was an assistant priest at St Patrick’s. Fr Van Houte heard confessions four hours per day six days per week. When Fr Van Houte entered the confessional on any given day, there were two, three, or four rows of people waiting to have their confession heard. Fr Van Houte was a popular confessor because of the profound, but balanced and sensible advice he gave. During the time Fr Van Houte was at St Patrick’s he heard over one million confessions.

William Davis

The construction of St Patrick’s Church Hill was completed in 1845, long before the Marists firstarrived in Sydney. St Patrick’s has a prehistory which goes back to the early years of the 19th century when a former Irish convict, transported to New South Wales for his part in the uprisings of 1798, William Davis, acquired land in the Rocks. At a time when there was no Catholic priest in the colony, Davis’ home became a place of prayer. It would seem that a Catholic priest, Fr Jeremiah O’Flynn, briefly in the colony before he was deported, left the Blessed Sacrament in Davis’ home. Pious Catholics between 1818 and 1819 had the consolation of being able to adore the Blessed Sacrament at a time when there was no priest to celebrate Mass. In 1840 William Davis donated the land on which St Patrick’s stands, as well as contributing a substantial sum, to its construction.

Faithfully Conserving the Message

But back to The Doc! According to The Doc:

“The primitive preaching has a ‘traditional’ character , that is the word preached by the apostles and the witnesses is received and transmitted in a community conservative of it, bent upon receiving the message with exactness, upon conserving it and transmitting it faithfully.“

Witness

The Doc quotes, with approval, C H Dodd, the Welsh Protestant scripture scholar:

“The primitive church was a well-defined and firmly organised community. It had an acute sense, both of its own responsibility to spread the faith, and of its own responsibility with regard to the truth of what it preached. One of the most common words of the Old Testament is ‘witness‘. The Christian community operating by means of its accredited agents, the apostles, evangelists, and doctors, has always retained as a point of honour to tell the truth as a witness in court. This is the atmosphere in which the oral tradition took form.”

Proclaiming Jesus

The Doc further comments:

“The historical preoccupation of the community is likewise manifest in the structure of primitive preaching. The kerygma did not consist in fact in a statement of abstract truth (for example, on the goodness or mercy of God), but in the proclamation of the principal facts of the life of Jesus, in which appeared the salvation of God. If there was little interest in history as a science…the community had nevertheless need of the historical datum, because only in this certitude could it be secure in possessing salvation…For this reason recourse was had to ocular witnesses to know how Jesus acted on the various occasions and to draw therefrom a rule of life.”

Common Life

The Doc further comments:

“Jesus…intended… to be a teacher, and in the sense understood by the ancients, that is, one who leads a common life with his followers. This fact of itself alone favours the rise of traditions, in the bosom of the group of pupils, of his teaching. But Jesus appeared as a teacher-prophet, that is, one who bore the word of God. His teaching appeared on that account as a charismatic answer to the most grave religious problems of his time…The common life with Jesus, becoming something stable, must have given occasion to another need to put together, and conserve certain words of Jesus: the need of the disciples to have clear before their eyes the principles of their life, whether insofar it regarded the obligations of their calling and its demands of totality, or in as much as it concerned the practical consequences of their state of life and their fundamental duties.”

Hierarchically Organised

The witness provided by early Christians involved constant reference to the hierarchically organised group, the Church. After the appearance of Jesus to Paul, and Paul’s conversion, Paul came to Jerusalem where Barnabas “brought him to the apostles…So [Paul] went in and out among them at Jerusalem, preaching boldly in the name of the Lord.” The Doc notes that Paul, who boasts, in Galatians, of having received the apostolic office from the risen Christ, goes to Jerusalem after his sojourn in Arabia, and remains fifteen days with Peter. After the firstapostolic mission Paul contacts Jerusalem “to make sure the course I was pursuing, or had pursued, was not useless“: Gal 2:1. The decision of the Council of Jerusalem, attended by Paul and Barnabas, as to the obligations of gentile converts, and Paul’s later visit to Jerusalem to discuss the same issue, demonstrate that, from the first, the Church was hierarchically organised. Peter’s report to the Church in Jerusalem, following his vision, and encounter with the centurion Cornelius, demonstrates the hierarchical organisation of the Church from the beginning.

Witness

The witness from the beginning, in union with the Apostles, is integral to Christianity. This is evident, for instance, in the Missionary Discourse in Matthew 10. By the end of Matthew, the mission to the lost sheep of Israel has become a mission to all nations. The Gospels are the fruit of Apostolic preaching within the institutional framework of the early Church, being reflections on the life of Jesus of Nazareth in the context of the Jewish scriptures. From the very first the early Church was concerned with unity, with true belief, with avoiding dissension, avoiding false teaching, avoiding disputes over matters of no importance, with being open to everyone.

Oral Tradition

The prehistory of the Gospels is a prevalently oral prehistory. This makes the Gospels quite different from other literary works, then or now. The Gospels are the fruit of a continuous and established oral tradition dating from Pentecost. This oral tradition involved prayer and contemplation by the Apostles, and consideration of the events of the life of Jesus of Nazareth in the context of the Jewish scriptures which foreshadowed the prophet from Nazareth.

Scholars have suggested the existence of one or more documents no longer available, from which the synoptics are drawn. This is entirely possible, though impossible to specifically establish. Luke at the beginning of his Gospel says: “Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things which have been accomplished among us, just as they were delivered to us by those who were from the beginning eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, it seemed good to me…to write an orderly account…that you may know the truth concerning the things of which you have been informed.” This suggests an oral tradition from which sprang later written documents, no longer extant, the source of the Gospels, all in the context of the apostolic tradition. From the beginning what is evident is a closely defined oral tradition.

History

As Woodbury argues, the Gospels are not history in the sense of contemporary historical scholarship, but they involve the recounting of actual events by witnesses to those events, by witnesses who were concerned to recount the truth. The Gospels are not much concerned with establishing the absolute or relative chronology of the events of Jesus’ life. They are not concerned to note accurately the journeys taken by Jesus, nor to record the names of persons of whom the knowledge would be important for writing an exact biography of Jesus.

The principal concern of the Gospel writers is to spread faith in Jesus. The sayings and deeds of Jesus are an indispensable support for this faith, and were, consequently, the object of scrupulous transmission, but not of scientific inquiry.

Agony in the Garden

Matthew provides the most detailed account of the Agony in the Garden. The importance of the Agony in the Garden in Catholic life is highlighted in the First Sorrowful Mystery of the Rosary, as well as in Catholic art, particularly Renaissance art.

Jesus asks little of the disciples, simply: “Sit here, while I go over there and pray“. Of course, if the disciples were even half alive to what was happening, if the Apostles were not the deadheads depicted in the Gospels, they would realise more was required than mere “sitting”. But the disciples are dullards, empty vessels, blind and deaf to what was happening. No different from us! Jesus asks little from the disciples as, like us, they seem capable of little. These are events at the centre of history, and the disciples are off with the fairies, in Pixieland!

Jesus’ human will recoils at what lies ahead: “My soul is very sorrowful, even to death; remain here, and watch with me…My Father, if it be possible, let this chalice pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will“. But Jesus submits to the will of the Father: “My Father, if this cannot pass, unless I drink it, your will be done.” Here we have Jesus’ humanity, and also his relationship with the Father. Echoes of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Father…thy will be done.”

Mark recounts Jesus as saying: “Abba Father, all things are possible to you, remove this chalice from me, yet not I will, but you will.” Luke’s account of this is somewhat similar. But Luke alone recounts “an angel from heaven strengthening him“. Angels are characteristic of both Jewish and Christian belief. We should not forget our Guardian Angel.

Here, in the Garden, we have the filial relation with God the Father, the struggle of Jesus, the revulsion of Jesus, aware of the fate which awaits him. Echoes of the struggle for every single one of us, the struggle which is part of life, between our sense desire, and the good that we will.

In a way, Peter is Everyman, Peter is you and me: “So, could you not watch with me an hour? Watch and pray that you may not enter into temptation; the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.” Luke also has Jesus say: “Pray that you may not enter into temptation.”

In the end, Jesus is calm, decisive, in control, in a way his enemies are not. Jesus says to the disciples: “Are you still sleeping and taking your rest? Behold, the hour is at hand, and the Son of Man is betrayed into the hands of sinners. Rise, let us be going; see, my betrayer is at hand.” Mark recounts Jesus saying: “Simon, are you asleep? Could you not watch one hour? Watch and pray that you may not enter into temptation; the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.” The contrast between Jesus who is repelled by, but who accepts, what his Father asks him to do; and Peter, and the disciples, overwhelmed by torpor, is only too evident.

Hebrews

Arguably Hebrews 5:8-9 provides an interpretation, not only of the Agony in the Garden, but also Jesus’ suffering and prayer on the Cross:

“Son though he was, he learned obedience from what he suffered and, once made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.”

To my mind, the Agony in the Garden echoes many accounts in the Jewish scriptures where a person wills, and does not will, God’s will: Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac; Moses’ indecision at the beginnings of his leadership of the Hebrews; even the absurd reluctance of the prophet Jonah who runs away to sea to avoid God’s will, only to be swallowed by a great fish. The Agony in the Garden speaks to each of us, in what St Paul refers to as our double-mindedness, as we struggle to do God’s will in our own lives.

The Doc on the Agony In the Garden

What is characteristic of the Doc’s intellectual approach (leave aside his constant engagement at an intellectual level with those who have a different view) is the thoroughness of the manner with which he deals with any topic. This is illustrated in the almost twenty pages in which the Doc considers the Agony in the Garden.

Here I can only summarise part of what Woodbury has to say:

“The hidden and intimate passion of Jesus, a preparation for the grievous physical passion, is in full development and the Master again shows his divine foreknowledge and voluntary and conscious acceptance of sacrifice, though in the midst of extreme repugnance of rebellious human nature.”

Woodbury sees the Agony in the Garden, together with the temptations in the desert, as the “most dreadful” mysteries of the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Woodbury sees at work in this the “immensity of Christ’s love, the perfecting force of suffering and especially the offering in the person of Christ the ideal High-Priest of regenerated mankind. Jesus is going to be touched by sin in a sensible manner as in the temptation in the desert, and in this is realised Paul’s expression: ‘God has made him sin for us’. In the face of the reality of the passion, long prophesied and so much desired, and now to be fulfilled, the human nature of the Redeemer undergoes a profound and intimate reaction, seeming to rebel against the eternal Father’s grievous decree of salvation and to manifest an extreme degree of horror at unlimited suffering…The thought of the passion so terrifies Jesus that for a moment he appears incapable of reacting and is crushed by this disheartening sight.”

This incomplete account of The Doc’s interpretation of the Agony in the Garden demonstrates, both the significance of this episode in the life of Jesus of Nazareth, and Woodbury’s profound theological understanding.

St Thomas More on the Agony in the Garden

Another consideration of the Agony in the Garden is St Thomas More’s The Sadness of Christ, written in 1535 in the Tower of London, shortly before writing materials were taken away, shortly before More’s ‘trial’ before a kangaroo court, and execution on 6 July 1535.

Was Jesus’ Prayer Answered?

Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), in his Jesus of Nazareth trilogy, asks – was Jesus’ prayer in the Garden answered? Ratzinger’s profound nuanced reply is:

…the Father raised him from the night of death and, through the Resurrection, saved him definitely and permanently from death: Jesus dies no more. Yet surely the texts mean even more: the Resurrection is not just Jesus’ personal rescue from death. He did not die for himself alone. His was a dying ‘for others’; it was the consequence of death itself.

Hence this ‘granting’ may also be understood in terms of the parallel text in John 12:27-28, where an answer to Jesus’ prayer: ‘Father, glorify your name.’ A voice from heaven replies: ‘I have glorified it, and I will glorify it again.’ The cross itself has become God’s glorification, the glory of God made manifest in the love of the Son. This glory extends beyond the moment into the whole sweep of history. This glory is life. It is on the cross that we see it, hidden yet powerful: the glory of God, the transformation of death into life.’

Weight of Meaning

The Agony in the Garden is a myth, not in the sense of something untrue, but a true account from the life of Jesus of Nazareth, recounted by each of the synoptic writers, bearing a weight of meaning, otherwise inexpressible.

The Agony in the Garden resonates for each of us sleepyheads, each of us dullards, each of us witnesses to the great event of God incarnate’s intervention in human history, yet asleep to that intervention. The Agony in the Garden is an account given to each of us, who are full of promises of loyalty, but cowards at the first challenge to that loyalty, cowards at the first sign of danger.

Pray that we may not enter into temptation. The Gospel’s description of the Apostles, drop-kicks as they are, demonstrates that there is hope, even for us, if we engage in the struggle which is the life of any Christian.

Michael McAuley

Monday 11 March 2024