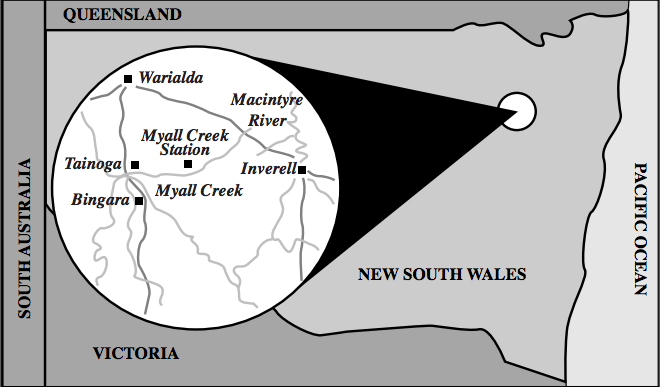

On 10 June 1838, at what was then Myall Creek Station near Inverell in North-Western New South Wales, a group of 12 stockmen rounded up at least 28 Aborigines, children, women, and men, murdering them, and burning the bodies. There was nothing unusual about what has come to be called the Myall Creek Massacre.

Planned Operation

Professor Lyndall Ryan of the University of Newcastle in Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre (2018) describes the Massacre as follows:

Although it was carried out in broad daylight by armed stockmen on horseback, the victims were a group of Aboriginal people who were not known to have killed a white person, let alone taken livestock. Yet it was clearly a planned operation. The…assassins who galloped into Myall Creek station late on Sunday afternoon, 10 June 1838, were well aware that the overseer, William Hobbs, was absent, and that the Wirrayaraay people were innocent of alleged crime. The assassins’ tactics were more like the brazen behaviour of vigilantes who believed they could do anything they wanted. They forced the only stockman at the station to join them while they tied up the 28 Wirrayaraay people in full view of at least two witnesses and then drove the victims to their fate around a hill more than a kilometre away, out of sight of the station huts. The witnesses heard two shots fired and then silence in the falling darkness. The next day the assassins returned and began burning the horribly mutilated bodies of their victims. Their act of terror was made even worse by the fact that they were led by a young settler who came from one of the oldest colonial families in New South Wales…The detailed explorations of the massacre by earlier historians clearly demonstrate that Myall Creek was simply one of many massacres in the region at the time and that the assassins were well experienced in the practice of killing large numbers of Aboriginal people in one operation. The only aspect which marked it out from the others was that the massacre was reported, that all but one of the assassins were arrested and charged with murder, and that seven of them were convicted and hanged.

Public Opinion

There have been over 400 such massacres of Aborigines in Australia since the first European settlement in 1788, the latest as recently as 1926 in South Australia, and 1928 in the Northern Territory. In addition, there have been at least 26 instances where Aborigines have been killed as a result of mass poisoning. These facts of Australian history deserve to be far better known. These facts, both as to massacre of Aborigines, and as to mass poisoning of Aborigines, have the possibility of changing the public debate on Aborigines in Australia. Most Australians are probably unaware of the number and significance of mass murders of Aborigines, particularly during the 19th century colonial era. These murders were carried out by both colonial soldiers and police in the course of punitive expeditions, and by settlers, acting on their own initiative.

Since 1788, the dispossession of land on which the Aborigines lived, the murder of Aborigines, and the European diseases for which Aborigines had no immunity, have caused havoc in the lives of Australia’s indigenous inhabitants.

Big Bushwack

Mark Tedeschi KC comments in Murder at Myall Creek (2015):

It was primarily in these remote areas, outside the limits of location and beyond the reach of the law, where the most atrocious murders of Aborigines occurred. Their occupation of the land was forcibly terminated by those whose claim of right depended solely on the superiority of their arms and their willingness to engage in brutal suppression. Many of the landholders ruthlessly dispossessed Aboriginal tribes and disposed of their surviving remnants by driving them from their traditional hunting grounds, polluting or poisoning their waterholes, or justplain murdering them. White colonists had a euphemism for the sustained, systematic pursuit and murder of rural Aborigines: ‘the big bushwack’. Much of the work of dispossession, dispersal and disposal was done by hired hands and assigned convicts working for distant landholders living in Sydney or the larger country towns, who may not have visited their holdings for months or years at a time. The lowly rural workers and their convict charges thus became the instruments of genocidal pillage of land and clearing of native bush on behalf of wealthy, absent landowners.

Australian Legal Classic

Mark Tedeschi KC’s Murder at Myall Creek is an Australian legal classic written by, arguably, Australia’s most experienced criminal lawyer. Because Tedeschi has spent an adult lifetime appearing as a criminal advocate, he has particular insight into Plunkett’s role as a prosecutor, and the forensic choices Plunkett made. Tedeschi describes the murders at Myall Creek, and the subsequent trials in the broader context of nineteenth century colonialism, and in the light of the life of John Hubert Plunkett, Attorney-General and prosecutor. It is the particular merit of Murder at Myall Creek that Tedeschi presents those events in a broad historical context. Tedeschi’s Murder at Myall Creek should be read by every lawyer, every law student. Murder at Myall Creekshould be on every lawyer’s bookshelf. Plunkett’s memory is never to be forgotten. Murder at Myall Creek is a work for all time. One knows nothing about the history of Australian law if one has not read Murder at Myall Creek.

House of Commons

Tedeschi quotes a Select Committee of the House of Commons On Aborigines in the British Settlements which concluded that:

Too often their territory has been usurped; their property seized; their numbers diminished; their character debased; the spread of civilisation impeded…it might be presumed that the native inhabitants of any land have an incontrovertible right to their own soil; a plain and sacred right however, which seems not to have been understood. Europeans have entered their borders uninvited and, they, have not only acted as if they were undoubted lords of the soil, but have punished the natives as aggressors if they have evinced a disposition to live in their own country.

Territorial Rights of Aborigines

With regard to Australian Aborigines, Tedeschi again quotes the Select Committee: In the formation of these [penal] settlements, it does not appear that the territorial rights of the natives were considered, and very little care has since been taken to protect them from… violence

Failure to Protect Aborigines

What is exceptional about the Myall Creek massacre is that eleven of those responsible were arrested, and that seven of the eleven were eventually found guilty of murder, and sentenced, in accordance with the practice of the time, to be hanged. The first trial commenced on 15 November 1838, and resulted in acquittals. The second trial, involving a different charge, commenced on 29 November 1838, and resulted in guilty verdicts.

The nineteenth century colonial legal systems, despite their universal prohibition of murder, both before and after the Myall Creek trials, failed to protect Aborigines against murder, whether state-sponsored violence by soldiers and police, or violence by settlers, usually “beyond the pale”, in rural areas remote from the seat of government.

Community Hostility

There was tremendous hostility to the Myall Creek prosecutions, encouraged by squatters (who funded the defence at the two Myall Creek trials), and encouraged by The Sydney Morning Herald. TheSydney Morning Herald commented on the prosecution:

The whole gang of animals [this is a reference to the Aborigines] are not worth the money the Colonists will have to pay for printing the silly documents [this is a reference to the legal documents in respect of the Myall Creek prosecutions].

One of the jurors following the first Myall Creek trial is reported to have said:

I look on the blacks as a set of monkies [sic] and the earlier they are exterminated from the face of the earth the better. I would never consent to hang a white man for a black one. I knew well they were guilty of the murder, but I, for one, would never see a white man suffer for shooting a black.

John Hubert Plunkett

John Hubert Plunkett was, perhaps, the first Irishman, the first Catholic, to be appointed to high office within the government of New South Wales. Plunkett was born in 1802 to a relatively comfortable Catholic family in Ireland, nevertheless a family which had suffered for the faith. Indeed, Plunkett was related to the Irish Archbishop of Armagh, and Primate of All Ireland, Oliver Plunkett (now St Oliver Plunkett) (1625-81), who was martyred for the faith, the last priestin post-Henrician Britain to be hung, drawn and quartered in odio fidei, following the verdict of a kangaroo court. St Oliver Plunkett was canonised by Pope Paul VI in 1975.

John Hubert Plunkett was the beneficiary of the gradual liberalisation of anti-Catholic legislation in the United Kingdom, which legislation had oppressed Catholics from the time of the Reformation. Plunkett was called to the Irish Bar in 1826. Between 1826 and 1832 he regularly appeared on the Connaught Circuit. In 1830, Plunkett supported Daniel O’Connell’s candidates in Connaught, helping the Whigs to power in the United Kingdom Parliament. As a result of Plunkett’s support of O’Connell’s candidates, he was offered the position of Solicitor General in New South Wales.

Attorney-General

Plunkett arrived in Sydney in 1832 to take up the position of Solicitor General. Between 1 Augustand 5 November 1833, Plunkett appeared for the Attorney-General in the Supreme Court of New South Wales, conducting 91 criminal cases and obtaining 64 convictions. In 1835 Plunkett published An Australian Magistrate, the first Australian practice book of its kind. In 1836 Plunkett was appointed Attorney-General for New South Wales. It was as Attorney-General that Plunkett conducted the Myall Creek prosecutions.

Plunkett’s later career included membership of the Legislative Council (1843-1851); membership of the Executive Council (1843-1846); Inaugural Chairmanship of the Board of National Schools (1848); Chairmanship of the Welcome Committee for Archbishop Polding (1856); founding fellow of St John’s College within the University of Sydney (1858); membership of the Legislative Assembly (1858-1860); publication of On the Evidence of Accomplices (1863); Vice Chancellor of the University of Sydney (1865).

Significant Legal Reforms

Mark Tedeschi comments:

…There has been no Attorney General before or since who has had more influence on the passage of significant legal reforms than John Hubert Plunkett…His stand on a whole series of issues was progressive and farsighted. They included his views on:

- convict assignments,

- floggings,

- the abolition of military juries,

- qualifications for civilian jurors,

- the rights of emancipated convicts,

- the unrestricted power of magistrates,

- the obligation of the courts to punish those responsible for massacres of the aboriginal population,

- the right of aborigines to give evidence in the court,

- the division between church and state,

- elected rather than appointed Legislative Councils,

- responsible self-government,

- secular public educational institutions at primary, secondary and tertiary level,

- teacher education,

- the provision of secular public health services, and

- the death penalty.

Viewed in the context of his times, he showed great humanity, perspicacity, bravery and strength of purpose. In [Tedeschi’s view], he should be excused for those few idiosyncratic views that he espoused in later life that now appear retrograde and deeply flawed.

This was in an era of sectarian prejudice against Irish Catholics who were almost universally poor, almost universally uneducated, and otherwise disadvantaged. Yet Plunkett flourished by reason of his integrity, impartiality, ability, hard work and good judgment. Nevertheless, the squatters never forgave Plunkett for his prosecution of the Myall Creek massacre.

Plunkett’s Life

Plunkett’s life is described in Professor John Molony’s An Architect of Freedom (1973), and Tony Earls’ Plunkett’s Legacy: an Irishman’s Contribution to the Rule of Law in New South Wales (2009). Plunkett is also the subject of scholarly consideration by the late John McLaughlin, former Associate Justice of the NSW Supreme Court, in Australian Jurists and Christianity (2015). Possibly relevant is McLaughlin’s posthumous work, The Immigration of Irish Lawyers in Australia in the Nineteenth Century whose publication date is December 2023.

More than Rolling his Arm Over

McLaughlin argues that Plunkett did more as Attorney-General and prosecutor of the Myall Creek massacre than simply roll his arm over:

The second trial was not an instance of Plunkett… merely carrying out [his] duties as prosecutor… for the Crown. There could have been little official or professional criticism if Plunkett had accepted the outcome of the first trial, and after the acquittals, allowed the matter… to rest. But with characteristic Irish feeling for the victims, and a determination to pursue the ends of justice, without concern for any personal consequences to himself, Plunkett drew up fresh indictments. Thenhe had to sustain those indictments before the Full Court when they were challenged on the ground of autrefois acquit. Plunkett’s conduct regarding these prosecutions was hardly surprising. His sense of compassion for the oppressed, in this instance, the murdered Aborigines, resulted from personal experience.

Many others would not have prosecuted the murders of those 28 Aboriginal children, women and men. Plunkett not only prosecuted the murders, but persisted when the firstprosecution failed.

Never Again

Mark Tedeschi comments on the seven convictions obtained by Plunkett at the second trial:

That he was able to do this in the face of almost universal hostility to the prosecution was nothing short of miraculous. It would never happen again during the colonial period, or even after the federation of the Australian States in 1901.

Community sympathy, especially amongst the squatters, favoured the defendants, not the murdered Aborigines. That sympathy is illustrated by the reluctance of potential jurors to respond to the jury summons. The leader of the murderers, John Fleming, escaped arrest, and was never captured, never brought to justice, by the colonial authorities.

Other Heroes

Other heroes in this affair, in addition to Attorney-General John Hubert Plunkett, include:

- George Anderson, the convict hut keeper who had tried to convince the murderers not to kill the Aborigines and who later gave evidence against them.

- Magistrate Edward Denny Day who investigated the Massacre and was responsible for the arrest of the offenders

- Sir George Gipps, the newly appointed Governor of New South Wales, who supported the investigation, arrest and prosecution of the murderers. Following the two Myall Creek trials in May 1839, Governor Gipps issued the following edict:

As human beings partaking of our common nature – as the Aboriginal possessors of the soilfrom which the wealth of this country has been principally derived – and as the subjects of the Queen, whose authority extends over every part of New Holland – the natives of this Colony have an equal right with the people of European origin to the protection and assurance of the Law of England.

- William Hobbs, the manager of Myall Creek station, who reported the Massacre, and was sacked. Hobbs had to bring proceedings in the Supreme Court against his Myall Creek Station employer to recover money owing to him.

- Richard Therry, a barrister who appeared with Plunkett at the Myall Creek trials.

- Yintayintin (Davey), the Aboriginal labourer on the Myall Creek Station who followed the murderers at a distance and, while hidden in the bush, witnessed the murders, reporting back to the hutkeeper, George Anderson.

- 12 white jurors, who convicted the 7 defendants despite public opinion.

Legal Perspective

High Court Judge Jacqueline Gleeson has recognised, not only the significance of John Hubert Plunkett for Australian law, but also the significance of the concept of human dignity. Human dignity, although grounded in Judaeo-Christian scriptures, is a concept which can be considered both from the perspective of human reason, and from a legal perspective. In an extra curial paper, originally given to the Francis Forbes Society, Human Dignity in the Time of John Hubert Plunkett, Justice Gleeson has explored the impact of the concept of human dignity on the work of Plunkett.

Dignity Unites Other Rights

As to human dignity, Justice Gleeson refers to the plurality’s (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ) citation in Clubb v Edwards (2019) 267 CLR 171 at [50]-[51] of Professor Aharon Barak, a former President of the Supreme Court of Israel, writing extra judicially:

Most central of all human rights is the right to dignity. It is a source from which all other human rights are derived. Dignity unites the other human rights into a whole.

The plurality go on to quote Professor Aharon Barak where he says:

Human dignity regards a human being as an end, not as a means to achieve the ends of others.

See also Baroness Hale of Richmond in Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] 2 AC 557 at [132]:

Democracy is founded on the principle that each individual has equal value. Treating some as automatically having less value than others …. violates his or her dignity as a human being.

See Federated Municipal & Shire Council Employees’ Union of Australia v City of Melbourne (1919) 26 CLR 508 at 560-561:

…In 1884 it was well understood that ‘trade disputes’… had … to be more and more founded on the practical view that human labour was not a mere asset of capital but was a cooperating agency of equal dignity – a working partner – and entitled to consideration as such.

Marion’s Case

Justice Gleeson might have referred to the golden, albeit dissenting, words of Brennan J (as he then was) in Marion’s Case (1992) 175 CLR 218 at [266]:

Blackstone’s reason for the rule [relating to personal security] which forbids any form of molestation, namely, that “every man’s person (is) sacred”, points to the value which underlies and informs the law: each person has a unique dignity which the law respects and which it will protect. Human dignity is a value common to our municipal law and to international instruments relating to human rights…The law will protect equally the dignity of the hale and hearty and the dignity of the weak and lame; of the frail baby and of the frail aged; of the intellectually able and of the intellectually disabled… Our law admits of no discrimination against the weak and disadvantaged in their human dignity.

While Brennan J wrote in dissent, I doubt there would be any dissent that what Brennan J said accurately states Australian law.

Judicial Oath

Justice Gleeson might also have referred to the judicial oath, which, although it does not use the term “human dignity”, might as well – to do right to all manner of people, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will.

Inherent Value of Each Person

Justice Gleeson, after discussion of some of the literature, concludes:

Pulling these strands together, and without attempting to be exhaustive, human dignity is or may be concerned…with a recognition of the inherent value of each person, acknowledged as an equal value so that each person is accorded equal treatment and equal justice; with the manner in which persons are treated; with the prevailing sanctity of human life; and with the legal standing or moral presence of each person in society and in relation to others.

We are likely to become conscious of dignity when we observe its violation or non-recognition. If we experience our own degradation or humiliation, or observe the degradation or humiliation of others whom we consider to be worthy, we are likely to become interested in questions about our rights and the possibility of different and better treatment.

Myall Creek Trials

The trial judge at the first of the two Myall Creek trials, Dowling CJ, in his summing up to the jury, said the life of an Aborigine “is as precious and valuable in the eyes of the law as that of the highest noble in the land.”

The second trial judge, Burton J, reminded the jury that the Aboriginal deceased were “equally under the protection of God and the law“ and “equally liable to the protection of the law“.

Burton J commented:

The murder was not confined to one man, but extended to many, including men, women, children, and babies hanging at their mothers’ breast…slaughtered in cold blood. This massacre was committed upon a poor defenceless tribe of Blacks, dragged away from their fires at which they were seated, resting secure in the protection of one of the prisoners. Unsuspecting harm, they were surrounded by a body of horsemen…from whom they fled to the hut, which provided the mesh of destruction. In that hut the prisoners, unmoved by the tears, groans, and sighs, bound them with cords – fathers, mothers, and children indiscriminately – and carried them away to a short distance, when the scene of slaughter commenced and stopped not until all were exterminated, with the exception of one woman…The crime was…committed in the sight of God, and the blood of the victims cries for vengeance.

Elsewhere, Burton J said:

I hope I need not impress on your mind that it matters not in the sight of God or of the law whether that creature has a white or black skin. They are equally liable to the protection of the law.

Both Dowling CJ, the trial judge at the first trial, and Burton J, the trial judge at the second trial, demonstrated a mindset, strongly influenced by the Judeo-Christian understanding of human dignity.

By contrast to The Sydney Morning Herald, the Sydney Gazette reported:

The judge was deeply affected – to tears. His honour was listened to with the deepest attention by a crowded court, and we trust that the remarks which fell from the bench will have the effect they were intended to produce on the audience – of showing them that the black man, like the white man, has a soul to be saved, and that any outrage on the former by the latter will be as soon avenged as would be an outrage on the white man by the black savage.

Protestantism

The Myall Creek trials were about human dignity, the rule of law, equality before the law. Despite the sectarian nature of colonial NSW, orthodox Protestantism, in all its numerous forms, with its scriptural emphasis, embraced the concept of human dignity. Human dignity is as integral to Protestant as to Catholic thought. It is notable that the two trial judges, Dowling CJ, and Burton J, were Protestants. Plunkett was not some idiosyncratic Fenian on a wild goose chase of his own!

Where the concept of human dignity is rejected in practice by Christians, such rejection demonstrates intellectual inconsistency: believing and saying one thing, doing another.

Equal Application of Justice

Commenting on the significance of the Myall Creek trials, Tedeschi says:

Even among all these misgivings of the white population, the colony still had in common with the motherland the fundamental tenet of British law: that justice was capable of being applied equally to all persons if those who applied it were sufficiently determined.

Proto War Crimes Trials

Tedeschi further comments:

The trials in 1838 should be viewed as the ‘earliest proto war crimes’ trials in Australian history. There was undoubtedly an ongoing war, albeit rather one-sided, between the white settlers and the indigenous inhabitants whom they were attempting to displace. The war involved a systemic policy, approved or acquiesced in by the white authorities, of unlawfully exterminating those Aborigines who stood in the way of the expansion of white settlement, or posed a threat to the pastoralist and their farming activities. In the author’s view, the perpetrators of the mass murders at Myall Creek Station in 1838 were motivated by genocidal intentions and were an example of what we now called ‘ethnic cleansing’. The fact that almostthe whole tribe was decimated – including women and children – demonstrated only too clearly their genocidal intent. The subsequent sexual abuse of one female victim, which spared her life for what must have been a few excruciating days, illustrated the objectification of their victims… While the approach taken by John Plunkett towards the case….demonstrated an enlightened and visionary attitude that was unparalleled in his time or for more than a hundred years afterwards. John Plunkett did not just prosecute 11 men for murder. He prosecuted his society for its connivance in the attempted annihilation of the Aboriginal people and their culture.

Theological Perspective

A world away may seem Anna and John Rist’s 2023 “essay”, Confusion in the West: Retrieving Tradition in the Modern and Post-Modern World. This is an evaluation of Western philosophy from the Greeks to the present. Amongst many themes of the Rists’ work is the concept of the human person in Western thought. The philosophical perspective is the perspective of human reason.

John Rist is a professional philosopher who has taught almost all his adult life at the University of Toronto. Anna Rist taught Classics at the University of Toronto. The Rists write from a Platonic and Augustinian perspective. The Rists believe that, without a metaphysical perspective, moral philosophy or ethics degenerates into mere conventionalism, or pragmatism, or Nietzschean nihilism, or even totalitarianism.

To fully explore the Rists’ perspective, it is necessary to read other more “academic” works by John Rist such as What is Truth? (2008), Real Ethics (2001), Augustine Deformed (2014), and What is a Person? (2019).

The Rists accept the Judaeo-Christian view of human dignity adopted by Plunkett as opposed to the view, adopted by the perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre, their squatter supporters, and TheSydney Morning Herald, that not all humans are “persons” worthy of respect.

One of the strengths of what may turn out to be an enduring postscript to a lifetime of academic work by the Rists is that they have thrown overboard footnotes and other academic claptrap. The Rists state their views bluntly, leaving no doubt where they stand on both philosophical and historical issues. One way of reading the Rists is to read and reread Confusion in the West, using it as a guide to reading and studying other thinkers, especially some of the authors referred to in the chapter on contemporary personalism.

Genesis

A source for the idea of person adopted by Plunkett is the Bible which, in Genesis, has man “in the image and likeness of God”. This is the first anthropological teaching of the Bible, a teaching about the human person, which illuminates everything else the Bible says on the subject. The second Genesis creation account, an account involving the creation of woman, emphasises man’s social nature. Genesis recounts God saying: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.” The prohibition on wrongful killing in the Fifth Commandment, illustrated by the account of Cain’s murder of Abel, is to be read with the Genesis understanding of the human person, created in the image and likeness of God.

In Psalm 8, the writer asks:

What is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him little less than the angels, and you have crowned him with glory and honor.

In Wisdom it is said that God created man for incorruption, and made him in the image of his own eternity. Sirach expresses the duality of the human person: “The Lord created man out of earth, and made him into his own image; he turned him back into earth again, but clothed him in strength like his own.”

Gospels

The idea of the person, and the concept of human dignity, if only implicit, is a constant of Catholic thought from the time of Jesus of Nazareth to the present time. The Gospel accounts of Jesus of Nazareth build on the idea of human dignity at play in the Jewish scriptures, with the twofold law of love, the Golden Rule, the parable of the Good Samaritan, the parable of the Good Shepherd searching for the lost sheep, and so on. St Paul comments in Galatians:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

Second Vatican Council

See the Second Vatican Council’s Gaudium et Spes at [21]:

The Church holds that the recognition of God is in no way hostile to man’s dignity, since this dignity is rooted and perfected in God. For man was made an intelligent and free member of society by God Who created him, but even more important, he is called as a son to commune with God and share in His happiness.

Catechism of the Catholic Church

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992) continues the biblical tradition, seeing the divine image as “present in every man”.

Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church

See the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2004):

The Church sees in men and women, in every person, the living image of God himself. This image finds, and must always find anew, an ever deeper and fuller unfolding of itself in the mystery of Christ, the Perfect Image of God, the One who reveals God to man and man to himself…All of social life is an expression of its unmistakable protagonist: the human person…Men and women, in the concrete circumstances of history, represent the heart and soul of Catholic social thought. The whole of the Church’s social doctrine, in fact, develops from the principle that affirms the inviolable dignity of the human person.

Ratzinger on the Judeo-Christian Perspective

Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI) who is perhaps the most significant Christian thinker of the last100 years, in an originally unpublished essay written after he ceased to be pope, comments that the essential form of Christianity sprang from Judaism. According to this Judeo-Christian perspective, ‘the one God is above all human reality.’ In the pure transcendence that is his own, he is at the same time the guarantor of human dignity.’

Commenting on the book of Amos, Ratzinger says God’s message ‘signifies a commitment to justice with regard to all’, requiring, as is evident from the Pentateuch and the historical books of Israel ‘solicitude for the widows, for the orphans, and for the strangers…They are particularly loved and protected by God.’

Rationalisation

From the perennial Christian perspective, each of those 28 or more Aborigines murdered at Myall Creek in 1838, are persons created in the image and likeness of God. Any rationalisation of their murder, based on the colonial ideology that prevailed, more or less, in 19th century Australia, that Aborigines were not “persons”, the ideology espoused by The Sydney Morning Herald at the time, the ideology espoused by the squatters, is just that, a rationalisation.

Philosophical Perspective

The perspective from which the Rists assess Western philosophy involves the following:

…the centuries between Plato in the fifth century BC and Aquinas in the thirteenth century AD, witnessed the gradual formation in Europe of the concept of a universe created by a monotheistic, though Trinitarian, God, in which the laws of nature are of divine origin and human beings – composed of body and soul – are the supreme product of that creation and formed in God’s ‘image and likeness’: hence reflecting in their personhood divine ‘dignity’. In brief, they – we – matter.

Effectively, what the Rists argue is that one cannot understand what it is to be a person, to be possessed of human dignity, unless one has a metaphysical framework, such as developed by Plato, to understand the true, the good, the beautiful, to understand the concept of God, and hence to understand the concept of eternal law, natural law.

Alternative World View

The Rists speak of the alternative world view:

… with wars of mass destruction and deadly weapons hitherto unimagined; with bureaucracy, totalitarianisms of differing stripes and an increasing belief that man, in his desperately claimed autonomy, can manipulate not only material nature…but also his own. Westerners had come to believe that, the human race, having evolved from lower life forms, that process of evolution is now in our own hands…in self-proclaimed ‘liberal’ societies it was coming to be held that humans and humanity no longer ‘matter’ much, if at all: it is the system – hence power that comes to matter. Indeed, with God dead, why should we humans matter? And not only was God dead, but any kind of ‘transcendental’ metaphysic …

This alternative world view is enmeshed in materialism, rejecting any metaphysical understanding of reality, having a diminished idea of the person. This diminished world-view is exemplified by the ‘great’ totalitarian regimes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – Nazi Germany, the USSR, communist China – and by the pragmatic utilitarian technical view of the person which prevails in the economically ‘advanced’ nations of the modern world.

Amongst the thinkers highlighted by the Rists in their consideration of the nature of the human person in Western philosophy are Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, St Justin, St Augustine, Boethius, St Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Bartolome de Las Casas, Karol Wojtyla, Edith Stein, Elizabeth Anscombe, Alasdair Macintyre. Each of these thinkers deserves extended individual consideration, something which we cannot do here. The best we can do here is to provide a thumbnail sketch of the Rists’ view of these thinkers, some sense of the dialogue down the centuries as to what it is to be a person.

Early Christian Thinkers

The early Christian thinkers asked themselves: what aspects of pagan thought are true? what aspects of pagan thought are compatible with divine revelation? what aspects of pagan metaphysics can provide the underpinning of a Christian metaphysic? what must be discarded as alien? Initially the early Christian thinkers adopted a Platonic perspective, not merely based on a critical evaluation of Plato (428? – 348 BC), but of others within the Platonic tradition including Plotinus (204/205-270 AD). When the works of Aristotle (384-322 BC) became more readily accessible in the 13th century, Christian thinkers such as St Thomas Aquinas, tended to adopt a more Aristotelian perspective. St Thomas Aquinas drew critically from Moses Maimonides, a Jewish philosopher theologian, and from Al Farabbi, Avicenna and Averroes, Islamic thinkers. The Socratic approach is that of dialogue, an approach which has endured down the long history of Western philosophy to the present time.

Plato

Plato concluded that only transcendent metaphysical realities-truth, goodness, beauty– independent of human greed, power-seeking and lust-can provide the necessary standards for individual and communal lives. We must recognise the immaterial and unchanging principles of the universe in which we find ourselves. Later philosophers would recognise the transcendentals of truth, goodness, beauty as a reference to God.

Platonic and Aristotelian Philosophy

The Rists sum up the fundamental difference between Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy:

Plato teaches us to pursue a passionate desire for truth, beauty and goodness into an immaterial ‘beyond’ world, while his account of our composite nature needs the correction that Aristotle brought to it with his theory that we are active agents whose souls act as the ‘form’ of our bodies…We shall flourish, Aristotle claims, by acknowledging both our likeness and our unlikeness to the divine, also, as emphasised by Plato, that lacking any such likeness – established as it is by unchanging moral truths – our common life must collapse into social anarchy…Throughout all this we need to hold in view that in antiquity moral obligation is to be translated not in to respect for claimed ‘rights’, but into our duties to ourselves and the society in which we live: that is, into virtues.

St Justin and the Long Spoon

As to St Justin (100-165 AD), according to the Rists, he was:

The first Christian convert who we know sought to ‘cover his Christianity with a philosopher’s cloak’… Justin is important less as a philosopher than a Christian convinced that Christianity and philosophy, especially Platonism, are compatible. Like all his Christian successors, he would need the proverbial ‘long spoon’ if he was to ‘sup’ with those pagans whom many of his co-religionists would regard as diabolical: he needed, that is, painstakingly to sort out which features of (in particular) Platonic philosophy could provide the underpinning of a Christian metaphysic, and which to discard as alien to it.

So, St Justin inaugurated the Christian intellectual approach ever since, accepting whatever is true, whatever is good, whatever is beautiful, properly understood, from wherever it comes, in the confident assurance that such can never conflict with faith. There is no conflict between reason and faith.

Christological and Trinitarian Controversies

The Rists describe the philosophical understanding of the human person as developing in the context of controversies within the Church of the first millennium as to how Jesus of Nazareth can be said to be one person but possessed of twonatures, one human and one divine. And controversies within the Church of the first millennium as to how there can be said to be three persons in one God.

Person as Mask

Just how the concept of “person” developed from both Stoic and Christian thought is described by the Rists:

We read in Cicero that according to the Stoic Panaetius our individual nature can be analysed in terms of four personae (the Latin word derives from Etruscan and begins by meaning ‘masks’): each one ‘inside’ the other and each in turn supplying a more detailed picture of the life to which we are best suited. Thus the first and ‘outer’ persona shows our common nature as human beings; second our individual characteristics (propria naturia); the third our particular situation in society; the fourth the individual aptitudes for which we may find openings in our life situations – as that one may be apt for politics or for horticulture. If we take all these personae together, we shall have a grasp on our overall persona and hence what role we may rationally adopt among the opportunities available to us. We ‘persons’ are thus the ‘blends’ – to include our blend of soul and body – which render us more or less able to take on and perform our individual roles.

Blending

The Rists highlight the significance of that difficult Carthagian Christian Tertullian (160-240 AD):

In this wise would Tertullian in late second century Carthage expound to his hearers that there are three ‘persons’ in God and that the second of these ‘persons’ had united (‘been blended’) with the man Jesus. Once the concept had become established in Latin theology, it was inevitable that person-language would be used, not only to describe the nature and actions of the Christian God, but also of human beings understood as created in his image.

Original Tradition

Over time, emerged, according to the Rists, from a confluence of faith and reason, what the Rists call the Original Tradition, in part, the Christian understanding of the human person, and of human dignity, even if the term “human dignity” was not expressly used:

- The universe has been created from nothing by an omnipotent and immaterial God, source of the moral law in his own person and being.

- Man is best viewed as a conjunction of soul and body, possessed of self awareness, together with powers of discursive reason, intuition and an ‘erotic’ charge capable of raising him ‘by grace’ – that is, with divine assistance – spiritually above the level of his otherwise now ‘fallen’ state.

- Being possessed of a dignity as an image of the divine and able to recognise himself as part of a ‘transcendent’ cosmos preserved under the eye of its providential creator-deity, man organises himself best in communities based on the laws of nature.

- The contents of the ‘moral space’ he inhabits, however, were massively disputed and the later widely used designation ‘person’ is as yet only sketchily understood.

- Agreed on all sides was that for the world to be intelligible must depend the existence of a God whose nature gives us the ‘natural law’ and the immaterial human soul.

- Without these, we are reduced to an Epicurean ‘atheism’ or a corrosive scepticism while the ghost of a Thrasymachean nihilism lurks – and will reappear with the waning of the Ages of Faith.

This understanding of the human person, and of human dignity, persists even to the present day, here and there, but with all sorts of confusion. This understanding is challenged by what the Rists call the Alternative Tradition, really a medley of competing, partial, inconsistent and contradictory views, which have in common that they diminish the human person.

Two Approaches

One aspect of philosophy evident in the writing of Aristotle, Boethius, and St Thomas Aquinas highlights what it is to be a person: a rational animal, possessed of free will, thriving in relation with others. A second perspective evident in the writing of St Augustine, Richard of St Victor, Dun Scotus, Karol Wojtyla, highlights what it is to be a particular person. Yet another perspective, highlighted by Cicero, sees the human ‘persona’ as a mask by which we present ourselves to the world. So, the term ‘person’ is understood in somewhat different ways, both by classical thinkers and by their Christian interpreters.

St Augustine and Subjectivity

St Augustine (354-430 AD) dominated the thought of what is misleadingly called the Middle Ages. Augustine’s approach, while exemplifying the Original Tradition, illustrated in his Confessionsa more individual, more subjective perspective as to the human person, more rooted in personal history.

Boethius and Rationality

Boethius, as the Rists comment, the “astonishingly learned” civil servant, murdered in 526 AD by the Gothic King Theodoric, wrote The Consolation of Philosophy. Boethius came up with a definition of the “person” which emphasises rationality: a person is an individual substance of a rational nature.

Incommunicability and Relationality

According to Richard of St Victor (1110-1173 AD):

… [the] existence [of the human person] is ‘incommunicable‘: that is, the experience of each personis unique. Thus to the question, ‘What is it like to be Richard of St Victor? ‘, no complete answer can be given…he emphasises that [human persons] are relational beings, reflecting the ‘relationality’ of the Trinity, and, in authentic love, reflecting the Trinity’s inner life.

St Thomas Aquinas

The Rists, Platonists though they are, recognise the achievement of St Thomas Aquinas (1225-74). In five closely argued pages, the Rists summarise that achievement:

In Aquinas’ own words: ‘As [John] Damascene says, a human being is said to be made in the imageof God, insofar as by “image” is meant something with understanding, free in its judgment and with power in itself.’ As persons, we are not only possessed of a divine ‘dignity’ as images of God but are the source of our own actions, for which we are thus responsible….We possess cognitive capacities, broadly understood to include self-awareness; we are capable of deliberated actions; we deploy various skills, especially the use of language. In sum, we are ‘in act’, the first of our acts being that ‘act of existence’ by which we are distinguished from mere essences or natures. I am more than a mere thought experiment of humanity, being an existent example of my genus and species.

Uniqueness of Personal Existence

As to the human person, the Rists provide a significant criticism of Aquinas:

Aquinas…fails to account for the uniqueness of my personal existence. Qua metaphysician, and neglecting Augustine’s approach through biography, he represents individuality solely in quantitative terms, identifying us as individual substances differentiated materially. He thus accounts (as does Aristotle) for our plurality but not for our distinctiveness.

What makes me, me? as opposed to the fellow on the train sitting across the aisle? or my sister? or brother? or cousin?

Uniqueness of Individual

As to Duns Scotus (1265-1308):

…he rejects the Thomist interpretation of Aristotle whereby matter, ‘designated by quantity’, determines into individuality. For while the simple plurality of individuals (understood as within the human set) might thus be explained, the Thomist account fails to differentiate the unique individual: fails to distinguish Jack from Jill – or Jim.

Thisness

According to the Rists:

Scotus holds that ‘the ‘form of humanity’ cannot account for the uniqueness of the individual, since matter is in each individual case differentiated…he names the ‘thisness’, the haecceitas of things; readers of Gerard Manly Hopkins will be aware of the term. Yet Scotus, while recognising the problem, seems, in a concern for wider questions, to have missed its special significance for those individuals created, and thus dignified, in the image and likeness of God. Rather, while expounding…how our common human nature appears in each individual, he leaves the relationship between our ‘contracted’ (that is individual) being and our common nature rephrased rather than illuminated. To leave the question of the relationship between ‘form’ of humanity (representing our common nature) and our individual ‘form’ (identifying our ‘thisness’) parked in philosophic limbo, is to leave our unitary nature as human beings unintelligible. It would be for Edith Stein, in the twentieth century, to expound Scotus’ insight further.

Las Casas

Bartolome de Las Casas (1484-1566) was a slave owner from South America, who became a Dominican priest and later a bishop. According to Las Casas the Indians, indeed all human beings, have the right not to be enslaved, and the right to live as freely as anyone. Las Casas argued human dignity requires respect for natural rights. This is a matter of justice.

Las Casas’ argument is an extension of that of the Dominican Francesco de Vitoria (1483-1586), a lecturer at the University of Salamanca, Spain, who, controversially at the time, argued that Indians are human beings, persons in the full sense, formed in the image and likeness of God.

The Rists see the English evangelicals of the early nineteenth century, who had a large hand in the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, as intellectual descendants of Las Casas.

Contemporary Personalism

The Rists comment on Karol Wojtyla (who became John Paul II) as follows:

… Karol Wojtyla, recognised that Scheler’s phenomenology (devoid as it is of any Aristotelian, or better Thomist, metaphysic) is unable to offer an objective account of persons which would allow for their possible dignity. In The Acting Person, The Theology of the Body and elsewhere, Wojtyla developed a description of the sexualised human agent that serves as a useful correction to the Christian tendency to prudishness. Yet though managing to sound morecontemporary – and doubtless preoccupied after his election as Pope John Paul II – he failed to advance his metaphysical supplement to phenomenology much beyond that of Aquinas’ original.

Whether this perspective on Karol Wojtyla, the philosopher, is correct or not, the philosophical work of this philosopher turned pope, later St John Paul II, must be exposed to the same philosophical scrutiny as the philosophic work of any other philosopher.

Edith Stein

Edith Stein (1891 – 1942) was a Jewish convert to Catholicism, later a Carmelite nun, St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, murdered by the Nazis in Auschwitz. According to the Rists:

[M]uch necessary corrective to that [Thomistic] original, with reference both to the radical nature of sexuality in the human psyche and to the inadequacy of Aquinas’ account of individuals, had already been placed on the philosophical table, and appropriately by a woman. Edith Stein …was Husserl’s boldest and most original student ….Stein…would prove rational and level-headed – even, it appears, when arrested in Holland and transported to die in Auschwitz.

Empathy

Stein’s doctoral thesis under Husserl was on empathy, an eighteenth century theme she examines in a new and more sophisticated phenomenological setting…

Dependence

Stein’s account of dying, and the possibility of empathy with the dying – perhaps the mostperceptive yet proposed, as enriched by her experience as a nurse…implies a very different view of humanitywhich would accompany her to her violently truncated earthly end. It is not nothingness we fear but the loss of what we have, and have been given. What we desire to continue to receive is the ‘ever-new gift of Being ‘… we receive it as a gift…the necessary dependence of each of us not only on one another (as empathy testifies) but on the giver and our source. Hence she can move from a phenomenological vision of human life as given, to a religious and metaphysical account of that ‘given’ dependency. By recognition of the ‘necessary’ (that is non-dependent) existence of our source, we add an intelligible account of our perceived dignity to a better understanding of our dependent nature.

Metaphysical Uniqueness

…in reflecting on human nature we must pass beyond universals, that is linguistic terms which sum up the characteristics of various natural sets; such as humans, elephants, fleas, trees, etc. We must take more seriously the metaphysical uniqueness of each human being…metaphysics as traditionally developed cannot account for human individuality. That must be supplemented by biographical or autobiographical accounts of each individual life with its unique set of characterising courses.

Serious Metaphysical Reflection

…we need more serious metaphysical reflection on the first person aspects of each human individual…

Virtue Ethics

The Rists identify the significance of the work of Elizabeth Anscombe (1919-2001) and Alasdair McIntyre(1929 – ). Both are converts to Catholicism. Both are well able to hold their own in the world of secular philosophy:

Such ‘analytic Thomists’ are well equipped to argue with their colleagues in secular departments of philosophy so long as they keep their transcendental metaphysics in the background; however, their version of Thomism is only rarely enriched by personalist, first person insights or, as with MacIntyre, by a rich historical and sociological insight, so tends to appear as a more careful version of the older, more arid Thomism, of ‘strict observance’.

No Final Say

It seems to me that no one of the above thinkers has the final say, but each provides some philosophical insight into what is meant by the human person: created in the image and likeness of God; possessed of both material and immaterial aspects; directed towards what is true, what is good, what is beautiful; possessing human dignity; possessed of a unique individual history, a world within herself or himself, presenting a certain ‘persona’ to the world.

Philosophy involves an ongoing dialogue about truth, about goodness, and about beauty, about matters without which human dignity cannot be understood. Even those who get it wrong, who get it seriously wrong, contribute to the ongoing dialogue we call philosophy as we grapple with what they get wrong and why. Amongst those thinkers whom the Rists consider get it wrong in one way or another are Hobbes, Rousseau, Kant, Bentham, Mill, Marx, Nietzsche. Any philosopher who considers he or she has come up with the final word is far from the truth.

Philosophy & Theology

In this context, philosophy and theology nourish each other, providing insights directed according to the specific method of each, directed to the reality of things.

Empathy

One way of highlighting the inadequacy of so much enlightenment, modern and post-modern philosophy is to consider whether such thought provides sound reasons why actions such as the killing of defenceless Aboriginal children, women and men in the Myall Creek Massacre are wrong. How could, perhaps, a majority of colonists in nineteenth century Australia approve, or, at least, acquiesce in, such killing? and yet hold, at least notionally, to the human person as having been created in the image and likeness of God? or being possessed of inestimable worth? Empathy, it seems to me, is fundamental to ethics. An “ethical” theory, an anthropological theory, which cannot justify empathy with the Aborigines, the children, the women, and the men, the victims of the Myall Creek Massacre, is flawed.

Original Sin

Human beings have, at times, a strong tendency to do wrong, even in the face of clear knowledge of what is right. The Genesis account of original sin, so readily dismissed by latter-day ideologists of ‘progress’, and various forms of utopianism, is repeatedly demonstrated, in the course of ordinary living, as well as in any serious historical study to accord with empirical reality.

Dialogue

Have Anna and John Rist got it entirely right? Probably not. But they have contributed positively to a dialogue as old as civilisation itself, in a way which enhances, rather than destroys. The approach which Dowling CJ, Burton J, and John Hubert Plunkett took as lawyers, Anna and John Rist, consider from a philosophical perspective.

No Neutrality

The murder of the Aborigines at Myall Creek (and other massacres), and John Hubert Plunkett’s response as Attorney-General, and as a crown prosecutor, indeed his professional life generally, about which we have considerable knowledge thanks to John Molony, Tony Earl, John McLaughlin, and Mark Tedeschi, have important lessons for us, as lawyers, as persons.

To fully understand the significance of the murder of those 28 or more Aborigine children, women and men at Myall Creek, and Plunkett’s response, one must understand, as Las Casas eventually did, in the different context of Spanish colonialism, that human dignity is universal, that the law is to obeyed, that all are equal before the law, and that there are certain things one ought never do.

Others prominent in the tradition which says the lives of all humans demand respect include Martin Luther King who campaigned for civil rights for blacks in the United States; human rights activists on behalf of Uyghurs in China, women in Iran, refugees throughout the world; modern slavery activists.

Western Invention

Some, such as President Xi Jinping of China, suggest human dignity is a western invention, a motif of western imperialism. Some have rejected the very concept of human rights, at least, as applying at all times, in all places, and in all circumstances. Dignity belongs to us all, whether from Europe, or Africa, or Asia, or the Middle East, or America, or Australia and the islands of the Pacific.

Amongst those who in practice deny that the personhood of all humans ought be recognised are the perpetrators of mass murder of civilians in war or otherwise, the perpetrators of terroristattacks, the killers of religious and ethnic minorities. There are plenty of contemporary examples of this today, and in the past two centuries.

Impartiality as Regards Human Good

The Rists argue that, contra John Rawls, there can never be a state which is somehow neutral as regards truth, goodness, beauty, that a legal system cannot be “impartial” as regards human good. Any such pretence of impartiality will ensure the powerful enforce their will against the weak, that manipulation and pretence and fraud dominate.

Philosophical Confusion

The Rists argue that much contemporary discourse about both justice and human rights has no adequate philosophical justification. And that assertion of claims to justice and human rights, while holding to unsubstantiated theories as to the person, or “ethical” theories such as relativism, pragmatism, utilitarianism, Machiavellianism, totalitarianism, Nietzscheanism and so on, simply bespeak confusion, the holding of two or more incompatible and inconsistent philosophical theories at the same time.

Life is a participation in the true, the good, the beautiful, a participation which is not possible if one acts contrary to exceptionless moral norms. Certain acts, such as the murders of the Aborigines at Myall Creek, one should never do.

Michael McAuley

Wednesday 14 February