To understand the Melkites, often known as Greek Melkites, is to understand that Melkites are Catholics, Catholics who follow one of the oldest ecclesiastical traditions, one of the oldest liturgical rites, of the Church, a tradition which originated in Antioch, in Syria, where Christians were first called by that name: Acts 11:26.

The early Christian missionaries came from Jerusalem to Antioch, then one of the great cities of the Roman Empire. St Peter and St Paul came at different times to Antioch, forming a community which is the source of the Melkite tradition. St Peter is regarded as the first bishop of Antioch before he moved to Rome. St Peter was succeeded by Evodius, and then by St Ignatius of Antioch.

St Ignatius of Antioch

St Ignatius of Antioch wrote the Letters, one of the classics of the Apostolic Age, during his enforced journey from arrest in Antioch to execution in Rome. St Ignatius was thrown to the beasts in the Flavian Amphitheatre in Rome in the second half of the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98-117 AD). The writers of the Apostolic Age are Fathers of the Church who knew the Apostles.

Greek

This was a world in which the lingua franca was Greek, the language which had been made universal amongst elites as result of the conquest by Alexander the Great (d 323 BC) of much of the known world, in particular what we today call the Middle East. At the time of Jesus of Nazareth, despite conquest by the Romans of much of the then known world, the lingua franca continued to be Greek, the language of the intellectual and commercial elites. What we call the New Testament was written in Greek. The original language of the Melkites was Greek. Hence the Melkites are known as Greek Melkites. This is despite the fact that the Divine Liturgy today tends to be celebrated in Arabic, or the local language, in Australia, English.

Legalisation of Christianity

In 313 AD, following the victory of Constantine the year before at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Edict of Milan permitted religious freedom within the Roman Empire, legalising Christianity. Before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine received a vision – “In this sign [of the Cross] you shall conquer.”

Constantinople

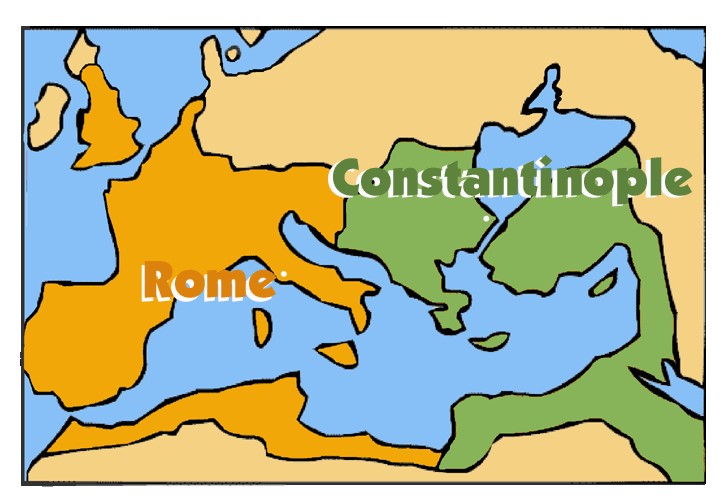

In 330 Constantine established Constantinople in modern day Turkey as capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, a decision whose effects are still felt today. What we call the Byzantine, really the Eastern Greek speaking, Roman Empire, was to last over a thousand years, to the end of what we call the late Middle Ages, till 1453, when Constantinople was finally overwhelmed by the Ottomans.

In 410 the Visigoths led by Alaric sacked Rome, providing the occasion for St Augustine’s writing of The City of God. In 455 the Vandals sacked Rome. In 476, following repeated barbarian invasions, the Roman Empire in the West (the portion of the Empire where Latin was more frequently spoken) collapsed. St Augustine of Hippo’s famous work, The City of God, is set around the sacking of Rome in 410 by Alaric.

Ecumenical Councils

The first seven Ecumenical Councils of the Church were: Nicaea (325); Constantinople I (381); Ephesus (431); Chalcedon (451); Constantinople II (533); Constantinople (680); Nicaea II (787). Each of these Councils was significant in defining Church doctrine. Each was the subject of everyday popular controversy at the time.

Chalcedon

The Greek Melkite Church derives from the Greek-speaking Fathers of the Church, and from the first seven Ecumenical Councils, in particular the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451). Chalcedon defined Christ as being one person united in both a human nature and a divine nature. Chalcedon was opposed by those we now know as Monophysites who asserted that Christ had only one nature, a divine nature. The understanding of Christ as one person, but with a divine and a human nature, has important repercussions for teaching on the Trinity, on Creation, on the Redemption, on Eschatology, on Ecclesiology, on grace.

At the time of the Council of Chalcedon, the then Byzantine (Roman) Emperor sought to uphold the Council’s teaching. The term “Melkite” was originally a term of abuse directed at those who accepted the teaching of Chalcedon, to which the Emperor subscribed. It is difficult for us today to appreciate how theological issues in the fifth century were a subject of popular controversy, much as political or social issues are today. The Melkites tended to be relatively sophisticated city-dwellers whereas those who did not accept Chalcedon, the Monophysites, tended to be country-dwellers.

The Melkite Patriarchs were originally to be found in Antioch, in Jerusalem, and in Alexandria. The Melkites were attached to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman empire). The Melkites like most of the Orthodox eventually celebrated the Byzantine Rite, celebrated in Constantinople. In the first millennium, there were a number of popes who are said to be Melkite. The Melkites had a role in the iconoclastic controversy, supporting the use of icons. Icons continue to be a feature of Melkite churches, as of all Eastern churches, to this day.

Phoenicians

Some Melkites are of Phoenician origin. The Phoenicians are referred to frequently in the Bible, most notably in the account of the encounter between Jesus and the Syro-Phoenician woman:

Jesus left that place and went to the vicinity of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know it; yet he could not keep his presence secret. In fact, as soon as she heard about him, a woman whose little daughter was possessed by an impure spirit came and fell at his feet. The woman was a Greek, born in Syrian Phoenicia. She begged Jesus to drive the demon out of her daughter.

“First let the children eat all they want,” he told her, “for it is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.”

“Lord,” she replied, “even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.”

Then he told her, “For such a reply, you may go; the demon has left your daughter.”

She went home and found her child lying on the bed, and the demon gone.

There are many aspects in this encounter with Jesus of Nazareth, but one aspect is the sense of humour so common among people of the region.

Split

Gradually, over the period from 863 to 1204, the Christian Church split between the Pope in Rome, in the West, and the Patriarch of Constantinople, in the East. The differences of language, of culture, of history, of theology, which had become progressively more apparent over time, reached a breaking point. The Greek-speaking Roman Empire in the East, Byzantium, the home of the Patriarch of Constantinople, continued until 1453 when Constantinople fell. This was the beginning of the Ottoman Empire, which prevailed in much of the Middle East, but which, in diminished form, we now call Turkey.

Remoteness of Split Between Rome and Constantinople

The mutual excommunications of Rome and Constantinople largely passed the Melkites by. This was a world where transport and communication was difficult. Most people lived and died, often in a village, within a short distance of where they were born. Whatever work they did, provided little opportunity for travel. Often the priest of the village had sufficient knowledge to celebrate the Divine Liturgy, but insufficient knowledge to appreciate theological differences, even theological differences of some significance. Education for clergy was difficult. The lower Melkite clergy in the village were Arabic speaking, whereas the higher clergy were Greek speaking, sometimes unable to converse with their Arabic-speaking people. This was a world where the differences between Rome and Constantinople, both far away, seemed remote. But Constantinople was geographically closer than Rome. There are difficult and complex historical judgments to be made here, possible, perhaps, only to a specialist well-versed in the language, culture, history and theology of the time and place, as well as the role of particular persons.

Arabic

The Melkites were persistently persecuted by their Muslim rulers, sometimes more harshly, sometimes less harshly. The Melkites nevertheless persevered in their old traditions, nourished by the Byzantine Divine Liturgy, and by the eastern intellectual tradition encapsulated in the writings of the Greek Fathers.

As the Muslims spread their religion by force of arms from the time of Mohammed (died 632), the common language of the so-called Greek Melkites became Arabic. Over time, the Middle East, inhabited by the Melkites (Greater Syria, Palestine, Egypt), was conquered by Muslims, who came from the Arabic peninsula. The Middle East became Arabic speaking. Arabic is the language of the Koran. Christianity passed from being the majority religion amongst the people of the Middle East to the religion of a small and persecuted minority. There was an increasing impetus to celebrate the Divine Liturgy in the spoken language of the people, Arabic.

Reaffirmation of Union

Only in the eighteenth century did the differences between Rome and Constantinople seem so significant that a choice had to be made whether or not to adhere to the Holy Catholic Church. In the seventeenth century, and even earlier, some Melkite leaders had been concerned to re-establish union with Rome. This was assisted by informal dealings with Carmelite, Dominican, Franciscan and Jesuit missionaries who fostered fraternal relations with the Melkites.

In 1724 the Melkite Church re-affirmed its union with the Papacy. In a sense the Melkites had never not been in union with the Papacy. Circumstances including geography had simply made that union difficult. In 1729 Pope Benedict XIII recognised the then Patriarch of Antioch, Cyril VI Tanas, and the Melkites, as being in full communion with the Catholic Church, and with the Pope.

Patriarchate Today

Today the Melkite Church led by the Patriarch Youssef Absi is in full communion with Rome. The Melkite Church may nevertheless be regarded as a bridge between East and West, between Rome and Constantinople. Through the Melkites, the West may understand the East, and the East the West, a way of healing the rupture which has gone on too long, fuelled by personality, language, history and culture, a rupture which arguably is more about accidentals than what is essential. The Melkite Patriarchate is today based in Damascus Syria, but the Patriarch is said to be the Patriarch of the ancient See of Antioch, as well as of Jerusalem, and of Alexandria.

World-wide there are perhaps 2 million Melkites, albeit estimates seem to differ. Increasingly, Melkites have fled the Middle East because of persecution.

Spread

Mass emigration occurred following the 1860 Damascus Massacre of Christians. After the 1952 Nasser revolution many Melkites left Egypt. The Melkites are still the largest Catholic community in both Syria and Israel. Catholics, including Melkites, have increasingly left Syria as result of religious persecution and war. There are significant Melkite minorities in Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine. The Palestinian journalist killed in 2022 in the course of her work on the West Bank, Shireen Abu Akleh, was a Melkite Catholic. Melkites are to be found in Egypt, Sudan, Iraq, Kuwait, as well as Turkey, Argentina, Australia, France, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, United Kingdom, Sweden, Austria, Italy. There are now Eparchies (dioceses) in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Australia and New Zealand.

Australia

The formal name of the Eparchy in Australia and New Zealand is The Eparchy of St Michael the Archangel of Sydney, for Melkite Greek Catholics of Australia and New Zealand. The name reflects that the Church is in harmony with the Chalcedonian tradition (Melkite), follows the traditions of the Greek Fathers (Greek), is in the fullness of the Gospel (Catholic).

The first Melkites in Australia came from the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. Among the first Melkites in Australia were the following families: Abou Khalil, Abou Samra, Bacharach, Bracks, Chahoud, David, Gazal, Herro, Maalouf, Mansour, Scarf.

In 1889 an enthusiastic Basilian Chouerite monk, Archimandrite Silwanous Mansour, came to Sydney to visit his parents. With the approval of his Father Superior, Archimandrite Mansour stayed in Sydney, visiting Melkite families, collecting donations for a Church to be named after St Michael the Archangel. In 1891 the foundation stone of a Church at 66 Wellington Street, Redfern, was laid. This was the first Eastern Christian Church in Australia. In 1895 the Church was inaugurated in the presence of Cardinal Moran. The Church of St Michael the Archangel became a meeting place for Middle Eastern faithful of various rites and religions. Between 1895 and 1990 the Chouerite monks served the parish of St Michael the Archangel.

St Michael’s Cathedral

St Michael’s Greek Melkite Catholic Cathedral continues at 25 Golden Grove Street, Darlington. The Cathedral at the new site was inaugurated in 1977. It was consecrated and blessed in 1981. It was formally designated a Cathedral in 1987. There are Melkite churches in all Australian capital cities bar Hobart, as well as in Canberra, and Auckland, New Zealand. In 1987 the Melkite Holy Synod appointed Bishop George Riachi the first Eparch for the Melkite Eparchy of Australia. In 1996 Bishop Issam John Darwish was elected as the Eparch. In 1999 Pope John Paul II extended the jurisdiction of the Eparchy to include not only Australia but New Zealand. In 1997 the chancery and the bishop’s residence was moved to Greenacre where is located the Church of St John the Beloved.

Eparch Robert Rabbat

The present Eparch in Australia is His Grace The Most Reverend Robert Rabbat. Bishop Rabbat was born in Beirut, Lebanon. In 1979, Bishop Rabbat moved to the United States to study engineering at Ohio State University. In 1982 he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Chemical Engineering, and a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics. Bishop Rabbat’s civil career saw him responsible for operations in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, supervising desalinisation and water treatment projects with Dupont de Nemours International, and as a project manager for the 3rd International Conference on Road Maintenance in the Middle East, under the auspices of the International Road Federation.

In 1989, Bishop Rabbat attended St Paul’s Institute of Philosophy and Theology in Harissa, Lebanon. He graduated with a double Licentiate in Philosophy and Theology. He was ordained in 1994 and undertook pastoral work in Lebanon. In 1995 he returned to the USA where he undertook pastoral work in Indianna. In 1997 Bishop Rabbat completed a degree in Communications from Purdue University, Indianna.

In 1999, Bishop Rabbat was appointed editor in chief of Sophia, a Melkite Diocesan magazine. In 2000, Bishop Rabbat undertook pastoral work in Illinois. In 2003 Bishop Rabbat was nominated to the board of directors of Tele-Lumiere International, Lebanon, the paramount Christian television broadcaster in the Middle East. In 2005 Bishop Rabbat was appointed rector of the Cathedral of the Annunciation, Boston, and elevated to the dignity of Archimandrite. In 2011 Bishop Rabbat received episcopal consecration, and became the third Melike Catholic Eparch of Australia, New Zealand and all Oceania.

Tradition

The Melkite tradition within the Church is growing rapidly, partly because of the depth and beauty of the Melkite Divine Liturgy, and the eastern theological tradition; partly because of marriage of Melkites with other rite Christians; and partly because Melkites tend to have positive attitudes to large families, and to children.

Nevertheless, secularization remains a challenge, as for all Christians, the unconscious absorption of worldly beliefs and ways of being, at odds with being a Christian. This challenge Melkites share with their brothers and sisters of other rites within the Catholic Church. All live in a world profoundly at variance with the way of Jesus of Nazareth.

Orientalium Eccelesiarum

The Second Vatican Council in Orientalium Ecclesiarum: Decree on the Eastern Catholic Churches (1964) made clear its esteem for the various rites which exist within the Church, including the Melkite Church:

The Catholic Church holds in high esteem the institutions, liturgical rites, ecclesiastical traditions and the established standards of the Christian life of the Eastern Churches, for in them, distinguished as they are for their venerable antiquity, there remains conspicuous the tradition that has been handed down from the Apostles through the Fathers and that forms part of the divinely revealed and undivided heritage of the universal Church.

The Holy Catholic Church, which is the Mystical Body of Christ, is made up of the faithful who are organically united in the Holy Spirit by the same faith, the same sacraments and the same government and who, combining together into various groups which are held together by a hierarchy, form separate Churches or Rites. Between these there exists an admirable bond of union, such that the variety within the Church in no way harms its unity; rather it manifests it, for it is the mind of the Catholic Church that each individual Church or Rite should retain its traditions whole and entire and likewise that it should adapt its way of life to the different needs of time and place.

Though not well-known, the Greek Melkites are as much part of the Church founded by Jesus of Nazareth as their Latin brothers and sisters. They are to be especially esteemed for their tradition, for their liturgical rite, and for their practice of the faith which reaches back to the beginnings of the Church.

We are all brothers and sisters in faith, members of the People of God.

Michael McAuley

Friday 15 September