St Thomas More was a martyr and saint to whom Cardinal George Pell had particular devotion. That devotion was publicly apparent from 2001 until 2014 when Cardinal Pell was Archbishop of Sydney, and Patron of the St Thomas More Society. Cardinal Pell’s perspective on law was the perspective of faith, but also the perspective of a historian, aware of the conflict between Church and state, recurrent in the history of the Church. That conflict between Church and state is recurrent, now to a greater extent, now to a lesser extent, because the martyrs, because the saints, because the Church, march to a different beat.

English Christianity

There were Christians in England within 100 years of the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth. During the Roman period, commencing in 43AD, Christianity was growing. After the Romans withdrew from Britain in 410AD, Christianity persisted, here and there, but with difficulty. In 596 AD St Augustine of Canterbury, the Apostle of the English, at the behest of Pope St Gregory the Great, arrived in England with his monks. Christianity began to reassert itself. Christianity in medieval England was built around the monasteries. The monks joined Christianity and learning. The life of the English people took place to the rhythm of the liturgical calendar, with Sunday Mass at which everyone gathered in the parish church; the great feasts and seasons of Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter, the Ascension, Pentecost, Corpus Christi; the numerous feast days of the saints and martyrs. Pilgrimages, veneration of Our Lady, and of the saints, were part of daily life. The bishops, as the most learned men in England, often occupied important secular offices.

The great works of English literature were Christian: Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People; the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf; various lives of the saints; Sir Gawain and The Green Knight; Langland’s Piers Ploughman; Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur; Various morality and mystery plays including Everyman and Mankind; and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

In 1144, Robert Pullen, an English theologian became the first English-born Cardinal. In 1152, Nicholas Breakspeare became the first, and so far, only English Pope, taking the name of Adrian IV. In 1159, John of Salisbury published Policraticus which argues that all political power is under God and all political rulers are subject to God. John of Salisbury was a friend of Pope Adrian IV. In 1162, John of Salisbury became secretary to Archbishop Thomas Becket. In 1363, Edward III appointed Simon Langham, a Benedictine abbot, as Lord Chancellor of England. Langham’s opening speech in Parliament was the first ever to be given in English. In 1366, Simon Langham, became Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1373, Julian of Norwich, a mystic and anchorite, received a number of mystical visions centred on the Holy Trinity. These meditations and reflections were written down and subsequently published as Revelations of Divine Love, the earliest surviving book in English, authored by a woman.

As Eamon Duffy argues in The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400 – 1580, medieval English Catholicism was, up to the moment of its dissolution, a highly successful enterprise, the achievement by the Church of remarkable lay involvement and investment, and of a corresponding degree of doctrinal orthodoxy. For the English at large, there was not much support for the Reformation. Yet, in the course of three generations from 1530 to the end of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign in 1603, one of the most Catholic of European countries became one of the most anti-Catholic.

Cardinal Wolsey

Corruption within the pre-Henrician English Church is well illustrated by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York, and Lord Chancellor before St Thomas More. Wolsey lost his position as Lord Chancellor because he failed to secure the nullification of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Wolsey died before Henry had the possibility of having Wolsey arrested, tried before a kangaroo court, and executed.

Henry VIII

The realpolitik of King Henry VIII, was intended to replace his Spanish Catholic spouse, Catherine of Aragon, with the younger and fertile Protestant, Anne Boleyn, with whom Henry was infatuated. This realpolitik largely destroyed the thousand-year-old English Catholic Church. Henry VIII relied on the pusillanimous bishops who were willing to accept him, contrary to both Scripture and tradition, as the supreme head of the Church in England. Henry VIII was able to rely on a grasping aristocracy which was eager to acquire the monastic estates. The older Henry VIII, under his Protestant Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell, despoiled the monasteries, those great centres of learning, of agriculture, and care for the poor. The funds were used to fund Henry’s foreign wars.

Henry VIII, despite early promise, developed many of the narcissistic and hubristic characteristics of Herod the Great, murdering many of his closest associates, including Anne Boleyn, the woman for whom he led England down the path of schism, indeed heresy, and Thomas Cromwell, the protestant Lord Chancellor, who masterminded the destruction of Catholic Christianity in England. Henry’s relationships with his successive wives demonstrates how flawed he was as a person, as a spouse:

- Catherine of Aragon died in her bed in 1538, albeit a virtual prisoner;

- Anne Boleyn was executed in 1536 at Henry’s behest;

- Jane Seymour was married to Henry within days of the beheading of Anne Boleyn. Jane gave birth in 1537 to the boy-king Edward VI whose advisers continued the policy of imposing Protestantism. Jane died shortly after Edward’s birth.

- Henry married Anne of Cleves in 1540 for foreign policy reasons. Anne was cast aside with the union apparently not consummated, and the marriage annulled six months later;

- Catherine Howard was married to Henry in 1540, but executed for alleged infidelity in 1542;

- Only Katherine Parr survived Henry.

There is evidence, Henry, upon his deathbed, repented. A fugitive priest heard Henry VIII’s confession, and administered the Last Rites including Viaticum. The mercy of Jesus of Nazareth is always there, even for such as Henry.

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII’s erstwhile Lord Chancellor, was unwilling to cooperate in the destruction of Catholic Christianity in England. More was beheaded, on 4 July 1535. Two months earlier, on 4 May 1535, at Tyburn, London, three Carthusian monks were executed in more grizzly fashion, the first of many martyrs of the English Reformation.

Sir Thomas More was an unlikely saint: twice married (his first spouse, Jane Colt, died) with four natural children as well as two adopted children; a lawyer, deeply involved in the politics of his time; an intellectual who epitomised the Northern Renaissance; a friend of Erasmus; for time a friend of Henry; a writer who, on occasion, could be coarse.

More was the author of Utopia, a classic which stands in the tradition of Plato’s Republic, and in line with the thought of Cicero and Augustine, about how best to order a commonwealth. Utopia is a work about the meaning of which scholars have argued for the past 500 years. More’s principal writings, collected by Gerard B Wegemer & Stephen W Smith in The Essential Works of Thomas More reveal a mind concerned with far more than theological issues. In Utopia More asks: should an intellectual serve the king? ought he enter the service of the king and counsel him for the best?

In the Epigrams, included in the early editions with Utopia, is a piece written by More for the coronation of Henry VIII containing nauseating flattery. Elsewhere, More comments:

“A devoted king will never lack children; he is father to the whole kingdom.”

And again:

“What is a good king? He is a watchdog, guardian of the flock, who by barking keeps the wolves from the sheep. What is a bad king? He is the wolf?”

More was no plaster saint, but a person who understood the complexity of things, and dealt on a daily basis with the uncertainties of life, and of the very different persons who came his way. Yet, as appears from the manner of his life, as recounted by his son-in-law, Thomas Roper, as appears from his Tower Writings, and as appears from the manner of his death, More was a saint.

English Martyrs

After St Thomas More’s execution in 1535, there was bloody persecution of English Catholics with numerous priests and laity being hung, taken down while still alive, drawn, and quartered. This bloody persecution continued during the reigns of Henry VIII (1509-1547), Edward VI (1547-1553), Elizabeth I (1558-1603), James I (1603 – 1625), Charles I (1625-1649), and Charles II (1660-1685). The reign of the Catholic Queen Mary (1553-58), daughter of Catherine of Aragon, involved a reversion to traditional Catholicism but, unfortunately, bloody prosecution of Protestants. It seems one area of agreement between Catholics and Protestants involved bloody persecution of their rivals.

The last of the Catholic martyrs was St Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, Ireland, hung, drawn and quartered, at Tyburn, on 1 July 1681. After the martyrdom of St Oliver Plunkett in 1681, there were no more judicial murders, but persecution and harassment of Catholics continued.

Glorious Revolution

In 1685, James II, a Catholic, briefly introduced religious toleration. This religious toleration as regards Catholics, ceased with the Glorious Revolution of 1689, and the accession of William and Mary. The exclusion of James II from the throne and of his heirs was extended to exclude all Catholics from the throne. The Sovereign was required in his Coronation Oath to swear to maintain the Protestant Reformation, a requirement that continues to the present day. The Glorious Revolution established parliamentary sovereignty, but also the continued banishment of Catholics from British life and society. Persecution and harassment of English Catholics continued to the beginning of the 19th century.

Catholic Relief Acts

In 1778 the Catholic Relief Act brought respite for English Catholics from some aspects of systemic persecution – abolishing the ban on Catholics buying and inheriting land, abolishing the life sentence for priests, and the life sentence for anyone convicted of running a Catholic school. In 1791, the enactment of the Second Catholic Relief Act meant that Mass was no longer illegal and could be celebrated openly; Catholic churches could be built; Catholic schools were permitted; and Catholic barristers could plead in court.

Catholic Emancipation Act

In 1829 the enactment of the Catholic Emancipation Act ended 300 years of persecution of Catholics, enabling Catholics to take their seats in both Houses of Parliament, the Lords and Commons, and enabling Catholics to vote in elections.

John Henry Newman

Between 1833 and 1841, John Henry Newman and others wrote Tracts for the Times, a series of theological publications which argued from an Anglo-Catholic perspective within the Anglican Church, seeking to marry the Thirty-Nine Articles, which formed the foundation of Anglicanism, with the Counter-Reformation teachings of the Council of Trent.

In 1834, Augustus Pugin, architect, was received into Church. In 1835, there were 510 Catholic chapels in England, whereas some 60 years earlier, there were only 30 Catholic chapels. In 1845, Newman was received into the Catholic Church. That year Newman’s essay On the Development of Christian Doctrinewas published. In 1850, Pope Pius IX restored the English Catholic hierarchy under the leadership of Cardinal Wiseman who was appointed the first Archbishop of Westminster.

In 1852, John Henry Newman, in the Pugin designed chapel of St Mary’s College at Ascot, said in a sermon: The English Church was, and the English Church was not, and the English Church is once again. This is the portent, worthy of a cry. It is the coming of a Second Spring; it is a restoration in the moral world, such as that which yearly takes place in the physical.

In 1863 a dispute between Newman and Charles Kingsley prompted the writing of Apologia Pro Vita Sua. In 1870 Newman’s Grammar of Assent was published. In 1879 John Henry Newman was made a Cardinal by Pope Leo XIII.

In 1890 there were 946 Catholic schools in England compared to 350 in 1870. There had been 83,000 students enrolled in Catholic schools since 1870. This had increased by 1890 to 224,000. By 1890 there were 1,335 churches and chapels in England compared to 469 in 1840.

From the mid-19th century continuing up to the 1950’s, numerous intellectuals who crossed the Tiber, had an influence on English intellectual life. These included John Henry Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Ronald Knox, Christopher Dawson, GK Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, JRR Tolkien, Malcolm Muggeridge. Others, such as TS Eliot and CS Lewis, who did not cross the Tiber, remained, in their own way, sympathetic to Catholicism, and had an influence on English intellectual life.

More and Fisher

St Thomas More appears from time to time in Cardinal George Pell’s three volume Prison Journal. StThomas More died, as he said, Henry’s good servant, but God’s first. In these words, More summed up, accurately, his own life, and also the life of St John Fisher, the only English bishop to reject Henry’s assertion of authority over the Church, the only English bishop not to fall into line with Henry’s destruction of the Catholic Church in England. St John Fisher, who was beheaded at the behest of Henry VIII, on 22 June 1535, also appears from time to time in Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal. Both More and Fisher were beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886. Both More and Fisher were canonised by Pope Pius XI in 1935. Both More and Fisher share the same feast day in the liturgical calendar, 22 June. More and Fisher are only two of the innumerable English and Irish Catholics who died for the faith, only some of whom have been formally beatified or canonised.

St Thomas More Society

As Archbishop of Sydney from 2001 to 2014, Cardinal Pell was Patron of the St Thomas More Society. Whenever Cardinal Pell could, each year, at the beginning of the Law Term, he celebrated the Red Mass. On 8 June 2006, on behalf of the Archdiocese of Sydney, Cardinal Pell donated, to the Parliament of New South Wales, a life size sculpture by Louis Lauren of St Thomas More. The sculpture was placed in the Speaker’s Garden where the St Thomas More Society often holds its annual Christmas Party. Cardinal Pell spoke at length about St Thomas More. That address is reproduced below. Cardinal Pell, while he was Archbishop of Sydney, each year, attended the St Thomas More Society’s Christmas Party.

Church and State

Cardinal Pell’s addresses, as well as his published writing, demonstrate a particular awareness of the importance of law. This is apparent in his 2007 collection of addresses, God and Caesar: Selected Essays on Religion, Politics & Society.

Cardinal George Pell, intellectually enriched by his studies, both in Rome, and at Oxford, had the mind of a historian. He understood the complexity of events, the complexity of human beings. Nothing was simple. Cardinal Pell’s writings demonstrate a particular awareness of the tension which can existbetween Church and state.

St Thomas Becket

Such tension between Church and state was apparent in 1170 when St Thomas Becket, then Archbishop of Canterbury, was murdered, apparently at the behest of King Henry II. That tension between Henry II and Thomas Beckett was the subject of a series of lectures given by the former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, James Spigelman, sponsored by the St Thomas More Society under the presidency of John McCarthy KC. Cardinal Pell attended those lectures. Those lectures were published in 2004 as Becket & Henry: The Becket Lectures with a Foreword by Cardinal Pell.

Cardinal Pell wrote:

History has shown that Church leaders are more than capable of presiding over and even becoming front runners, not only in religious mediocrity, but in wide-spread corruption. But there is much less hope of avoiding these fates when the Church leadership becomes subservient to ‘worldly’ power, whether that is exercised by kings, or politburo, or the media, or parliaments, or ‘reformist’ judges.

Becket’s murder in his own Cathedral became the stuff of legend. But his death in that small kingdom on the edge of the world inspired Church reformers across Europe to demand the space they needed. As the senior Archbishop in England, Thomas was right to resist Henry’s demands for total control.

St Thomas Becket’s shrine became the greatest centre for pilgrimage in Britain and Ireland. Miracle cures were legion. To the ordinary Catholic and citizen, it was a symbol of resistance to royal tyranny, some hope of protection. It was a rebuke to the pretensions and cruelty of Henry VIII nearly 400 years later, and he destroyed it.

More importantly, however, for Christians, Canterbury Cathedral became a shrine to Christian martyrdom, a source of blessings and goodness.

Spigelman on More

By way of excursus, I should say that Chief Justice Spigelman, while Chief Justice, gave many addresses which demonstrate a remarkable understanding of the relationship between law and justice. Amongst those addresses are the Opening of Law Term Speeches 1999-2010 where, in the 2008 speech on Commitment to the Rule of Law, Chief Justice Spigelman had the following to say:

Sir Thomas More is, of course, one of history’s exemplars of

commitment to the rule of law. This is best reflected in the well-known

passage from Robert Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons in which Sir Thomas

More rejects the religious fervour of his future son in law. More asserts

that he knew what was legal, but not necessarily what was right, and

would not interfere with the Devil himself, until he broke the law. The

following exchange then occurred:

‘ROPER: So now you give the Devil benefit of law!

MORE: Yes. What would you do? Cut a great road

through the law to get after the Devil?

ROPER: I’d cut down every law in England to do that!

MORE: Oh? And when the last law was down, and the

Devil turned round on you – where would you

hide Roper, the laws all being flat? This

country’s planted thick with laws from coast to

coast – man’s laws, not God’s – and if you cut

them down … d’you really think you could stand

upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes,

I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own

safety’s sake.”

This imagery of the law as a protection from the forces of evil is an entirely appropriate one. Each society has its own devils, some real, some imagined. The forest of laws that are planted under the rule of law protects us from those devils.

One of the principal reasons why the judicial task is often thankless and prone to controversy is precisely because we are obliged to protect the legal rights of unpopular people. The judicial oath requires no less.

Chief Justice James Spigelman had a broad understanding of law, not merely as a technician, but from a historical and philosophical perspective. It was a great loss to Australia that Chief Justice Spigelman was not appointed to the High Court.

Magna Carta

The tension between Church and state was also apparent in 1215 when King John reluctantly agreed to Magna Carta. Archbishop Steven Langton, then Archbishop of Canterbury, was, at least in part, draftsman of Magna Carta. At issue in the conflict between Church and state in England, was not merely freedom for the Church but the rights of ordinary English men and women.

Tuckiar

Cardinal Pell understood and admired the ethos of the law, no better expressed than by the High Court of Australia in R v Tuckiar (1934) 52 CLR 335 which concerns the obligations of a trial judge in the Northern Territory, and of defendant’s counsel, to ensure a fair trial on a charge of murder, the defendant being an Aborigine who spoke no English, and who, according to the headnote, was “completely uncivilized”. The ethos of the law, in particular the High Court, is to accord justice according to law to all, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will.

Although Cardinal Pell had no formal qualification in either civil or canon law, he had an understanding of law at its best, and of lawyers at their best. Cardinal Pell’s understanding of the law at its best became evident at his two trials in the Victorian County Court, and the appeals to the Victorian Court of Appeal, and to the High Court. Cardinal Pell was willing to instruct lawyers for their ability, regardless of religious belief, and was willing to take their advice.

It was only when Cardinal Pell got to the High Court that he encountered a bench of judges with the independence, the objectivity, the freedom from ideological prejudice, that reversed his conviction 7 nil. The High Court of Australia had in Tuckiar’s Case demonstrated the independence and objectivity to regard the racism that prevailed in the Northern Territory in the 1930’s for what it was. The High Court of Australia had the same independence and objectivity to regard the ideological hostility of the Victorian government and its appointees in the early 21st century for what it was. Australians have reason to be proud of the High Court of Australia, one of the great courts of the world.

Royal Commission into Institutional Response to Child Sexual Abuse

The Royal Commission made “findings”, disregarding the evidence, at its hearings in relation to the Diocese of Ballarat, and the Archdiocese of Melbourne. The evidence was, and is, that Cardinal Pell was a reformer, with his establishment of the Melbourne Response, one of the first leaders in Australia, and in the world, to recognise sexual abuse in institutional settings, and to do something about it. Cardinal Pell was a fall guy for the failures of Bishop Ronald Mulkearns of Ballarat, and Archbishop Frank Little of Melbourne. Both Bishop Mulkearns and Archbishop Little failed in their responsibilities to children, to parents, to the state, and to the Church, failing to address their obligations under both civil and canon law.

Intolerance to Religious Faith and Practice

Cardinal Pell understood the gathering contemporary intolerance to religious faith and practice, particularly Christian, indeed Catholic, faith and practice. That intolerance to Catholic belief and practice is evident in hostility to Catholic institutions being what they are, hostility to Catholic institutions adhering to Catholic belief and practice, hostility to Catholic institutions adhering to a Catholic ethos. Cardinal Pell was not the only Australian bishop, the object of this hostility. Cardinal Pell realised this antagonism to Catholic belief and practice exists, not only in Australia, but throughout much of the economically developed world. A contemporary illustration of this is the ACT Government’s plan to “nationalise” Calvary Hospital in Canberra, a plan that does nothing to enhance healthcare in the ACT, a plan that says nothing to Australian pluralism.

Cardinal Pell sought to respond to this religious intolerance with prudence, and also with courage. Cardinal Pell was never afraid to explain the faith clearly and intelligently. Cardinal George Pell’s faith was the faith of the Apostles, of the Fathers of the Church, of the innumerable men and women who, down the ages, have recited the Creed, believing literally all that it says, seeking to put it into practice, however inadequately, in their own lives. Cardinal Pell never hid behind scholarly obscurity. The prudence and courage which Cardinal Pell constantly demonstrated, and in which he emulated both StThomas More and St John Fisher, set him apart. Pell forgave his enemies, both his enemies outside the Church, and his enemies within. He was not bitter, he was not resentful. He accompanied in his own life the events leading to the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth. Cardinal Pell stands squarely within the Catholic tradition of being willing to suffer for the faith. In his published writings, Cardinal Pell refers to the Holy Innocents, St John the Baptist, St Peter and St Paul, St Ignatius of Antioch, the Forty English Martyrs including St Edmund Campion, the Japanese Martyrs of Nagasaki, and St Mary MacKillop. Suffering for the faith is an aspect of the Catholic tradition, an aspect which influenced Cardinal Pell.

Human Hope

The ideological hostility towards Cardinal Pell is to be understood in the context of conflict between Church and state which has ebbed and flowed since the beginning of Christianity. As Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI has commented, the state is not the whole of human existence and does not encompass all human hope. The ideological opposition to Cardinal Pell, both within, and without, the Church, reflects hostility to the hope which he epitomised, and which he expressed so clearly. It also reflects hostility to the presumption of innocence, and the right to a fair trial. What was at stake in the vendetta against Cardinal Pell were the fundamental rights and freedoms of all Australians.

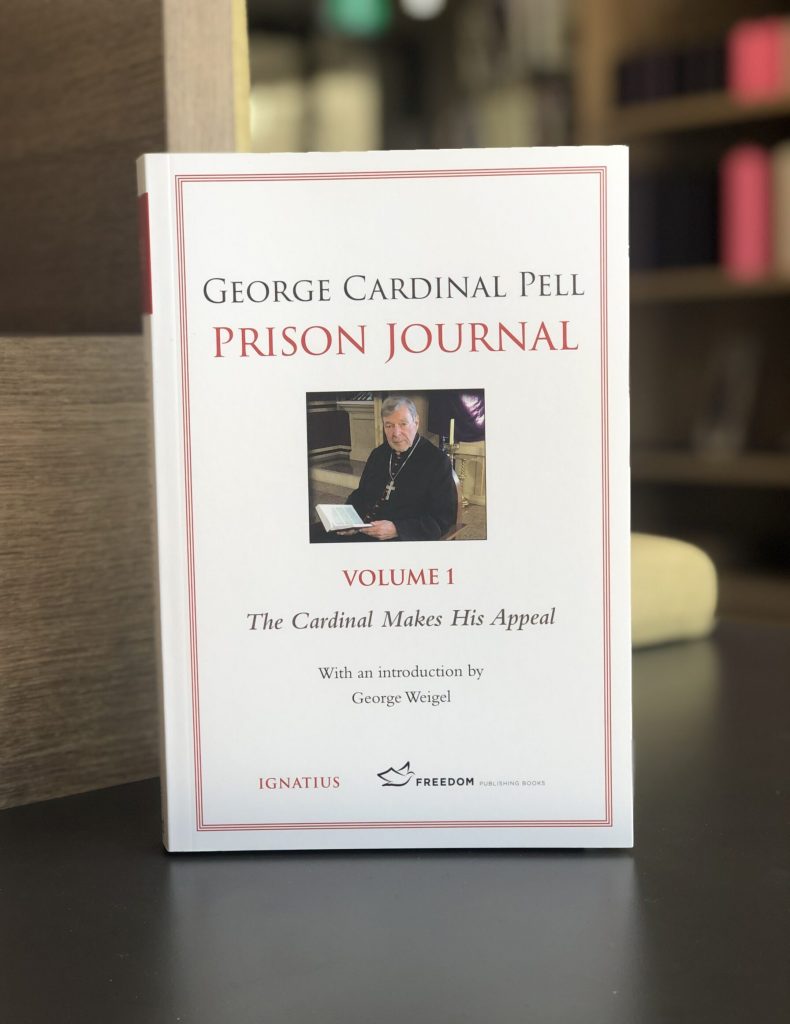

Prison Journal

Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal is the equivalent in contemporary terms of St Thomas More’s Towerwritings. The Tower writings of St Thomas More are A Treatise Upon the Passion of Christ, A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body, A Dialogue of Comfort, The Sadness of Christ— most conveniently accessed in Wegemer & Smith’s The Essential Works of Thomas More. Like Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal, the Tower writings reflect the mind and heart of the man, written at a time when More had limited access to books.

By the end St Thomas More was a Christ-like figure. The example of St Thomas More led Cardinal George Pell in the same way.

Michael McAuley

Pell on More

This year we are celebrating 150 years of responsible government in New South Wales, one of the oldest democracies anywhere in the world. This is a reason for pride and quiet celebration.

It is my privilege today to present to the New South Wales Parliament, on behalf of the Catholic community, a beautiful bronze statue of Sir Thomas More, who was born in England in either 1477 or 1478 and was beheaded on Tower Hill in London on 6 July 1535 on the orders of King Henry VIII.

This gift is a recognition of how much all of us owe to our Australian democratic practices and traditions, to the Westminster system of government which we have inherited, and to our politicians.

I congratulate the sculptor, Louis Laumen, on capturing More’s spirit. I believe that this beautiful piece will always be a silent but powerful reminder in this place of the need for high principles, service to the truth and, above all, moral courage.

More has been canonised as a saint and martyr and is the patron saint of statesmen and politicians. Robert Bolt’s play and film called him A Man for all Seasons, and More contributed significantly in many different areas.

More was a writer and religious controversialist, a lawyer, lecturer and envoy abroad, and with the Coronation of Henry VIII he began a brilliant public career. At the age of 26 he entered Parliament and held a succession of offices, becoming Privy Councillor, Knight, Speaker of the House of Commons, high steward both of Oxford University, his alma mater, and Cambridge University and eventually succeeding Cardinal Wolsey as Lord Chancellor in 1529. But we don’t commemorate and honour him today for those considerable achievements.

Catholics, in particular, and many others remember Henry VIII as a tyrant who executed many of those closest to him, including some of his wives, and split the Christian church in England from the Catholic Church. But when he ascended the throne, he was seen very differently. He was young, vigorous, genuinely religious, a good linguist and musician and a friend of the “new learning.” In fact, the English rise to power began with the Tudors, especially under his daughter Elisabeth. Perhaps the best modern parallel to understand the enthusiasm he generated was the election of J. F. Kennedy as president of the United States in 1960.

The first half of the sixteenth century in Europe was an exciting time. Columbus had not long discovered the Americas and in Italy, the Renaissance had produced Da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, and many others, as well as the Renaissance Popes, often worldlings or worse, but great patrons of the arts and of the return of the classics.

More helped bring the Renaissance to England. He was the friend of scholars such as Grocyn, Colet, and especially Erasmus. “You must be Thomas More or nobody”, Erasmus began at their first meeting, with More replying: “And you must be Erasmus or the devil.” He worked hard to have the study of Greek introduced into Oxford.

It was More who invited Holbein to England warning him that he might struggle for commissions, and it is through Holbein’s magnificent portraits and sketches that we understand Henry’s England so much better. This sculpture is based on Holbein’s portrait of More now in the Frick Gallery in New York. There, it hangs not far from the flat, evil face of Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, also painted by Holbein who consolidated Henry’s power through the suppression of the monasteries and was also executed by the same king for his pains.

More was brought undone by “the King’s great matter.” Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, was unable to produce a son and Henry wanted to marry Anne Boleyn. For various reasons, Pope Clement VII refused to allow the matter to be decided in England and refused to nullify Henry’s first marriage.

More was a cautious lawyer, who mistrusted his own ability to stand by his principles and took refuge in silence, although refusing to attend Anne and Henry’s marriage. Henry was probably inclined to compromise, at least at the beginning, but Anne was relentless, and the stakes were raised to assert Henry’s religious supremacy as head of the Church. On this Thomas would not budge.

Ironically, More had originally believed that the popes were a human development and had warned the young Henry against too close an alliance with the Papacy. Ten years of study brought him to the conclusion that the position of pope as a successor of Peter was divinely ordained. But once again that particular Catholic conviction is not the reason we honour Sir Thomas More in this place.

We are paying tribute to More’s courage, to his adherence to principle, to his opposition to tyranny. He did this with few companions and little support. Only one bishop, John Fisher of Rochester, shared his view about the importance of the pope, while most Catholics thought he had exaggerated things badly. His favourite daughter, Meg Roper, together with all his family, believed his sacrifices were unnecessary. Even more poignantly, during his entire lifetime, there were only a couple of popes who aspired to religious respectability and the Papacy became ruthlessly secularised. It was these excesses which provoked Luther and the Protestant Reformation.

More was a man of his times, and the title of saint does not imply life-long perfection. He regarded heretics as small “l” liberals today regarded as racists, while going further so that during his time as chancellor six Protestants were executed. We thank God that we have moved past such excesses.

More was a serious follower of Christ throughout his life, a clear example of an outstanding citizen nourished and inspired by religious principle. His Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation written during his 15 months in the Tower is a beautiful expression of faith and was a support and comfort to all who are suffering.

More was a loyal friend, and had many friends. He was a good family man with an unusual sense of humour. He had style to go with his substance. In his own final words at the scaffold: “I die the King’s good servant, but God’s first.” And he had lived as he died.

Cardinal George Pell

8 June 2006

Parliament House Sydney

From Cardinal George Pell (edited by Tess Livingstone). Test Everything: Hold Fast to What is Good. Connor Court Publishing, Ballan 2010