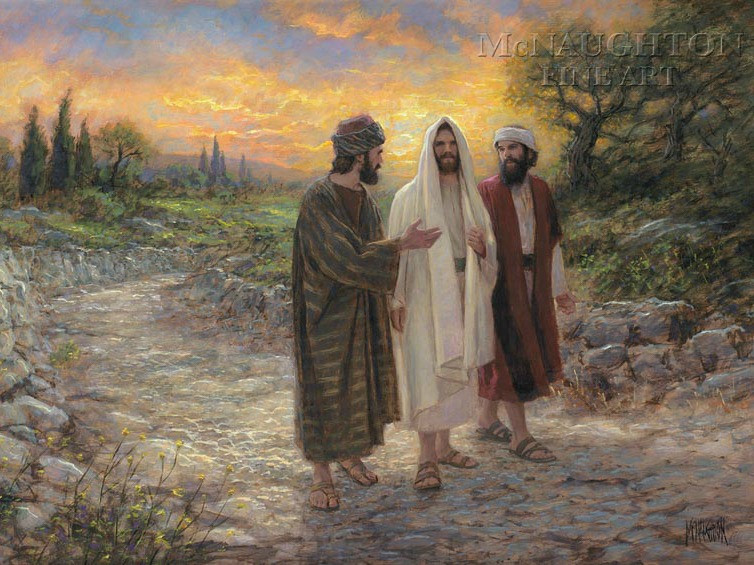

Late on the Sunday Jesus rose from the dead, two of his disciples, one of whom was named Cleopas, were walking the seven miles from Jerusalem to the village of Emmaus. The two wayfarers were discussing events of the past week, Jesus’ “trials” before the religious leaders, and before Pontius Pilate, the Roman Governor, Jesus’ crucifixion and death. At that point, a fellow traveller, also walking in the same direction, spoke to them. The two wayfarers had hoped Jesus was to rescue the Jews from Roman oppression, and to restore the kingdom of Israel as an earthly power.

Scriptures

The stranger, in response, explained the scriptures to them, starting from Moses and all the prophets, showing how all the scriptures looked forward to Jesus of Nazareth. The two wayfarers had to re-learn the Old Testament to understand the bewildering events leading to the death of Jesus of Nazareth. The narrative of the Hebrew Bible, of the Septuagint, is no remote writing, no ancient expression of times and places long since gone, but the key to understanding the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth – and, indeed, our own life and death which can only be understood in the light of the life and death of the Galilean. The events of the week culminating in the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth had to be understood in the light of God’s dealing with his people. Later, the Gospel accounts, written down, will be permeated with allusions to the Jewish scriptures. The events of the life of Jesus of Nazareth become apparent in the light of the word which had gone before. The learning on the road to Emmaus becomes the way the Church understands Jesus’ revelation of himself, in the light of God’s previous dealing with his people Israel. The Old Testament foreshadows Jesus of Nazareth, and Jesus of Nazareth is the fulfilment of all we read in the Old Testament.

Breaking Bread

When the two wayfarers reached Emmaus, they pressed the stranger to stay with them, it being close to evening. When he was at table with them, the stranger took the bread and blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. The two wayfarers in the breaking of the bread at once recognised Jesus of Nazareth who had been crucified. But Jesus vanished from their sight.

Return to Jerusalem

The two disciples returned to Jerusalem where they found the Eleven gathered together with others. They were told: “Jesus has risen indeed, and has appeared to Simon!” Here we have the event itself, Jesus’ resurrection, and the witness who confirms the event, Peter. Here we have, pithily expressed, the whole Christian message. Then the two wayfarers told what happened on the road, and how Jesus was known to them in the breaking of the bread.

Ratzinger

Joseph Ratzinger analysed this episode at least twice, once in 2011 in his Jesus of Nazareth trilogy, written in his “spare time” while Pope Benedict XVI, and previously, in 1968, in his Introduction to Christianity, published three years after the closing of the Second Vatican Council. Ratzinger’s two analyses, upon which I almost totally rely, are different, but demonstrate a continuity in the thought of the younger and the older Ratzinger. The 1968 analysis of the walk to Emmaus, focuses on love as transcending death, while the later analysis is more the work of a scripture scholar. Both are characterised by faith, in the absence of which theology betrays itself.

Resurrected Jesus

Ratzinger sees the Emmaus episode as demonstrating Jesus had risen from the dead. After the resurrection, Jesus walks and talks, eats, touches others, and is touched, but he is not immediately recognised, and in due course simply disappears. The resurrected Jesus appears through closed doors. So, the resurrected Jesus is not like the son of the widow of Nain; nor the daughter of Jairus, the head of the synagogue; nor Lazarus – each of whom were miraculously restored to life by Jesus of Nazareth, and went on living only, no doubt, to die eventually the death we all must die. While the resurrected Jesus could perform the actions of any human being – walking, talking, eating, touching and being touched – there are aspects to the being of the resurrected Jesus which are quite different. Jesus’ actions after the resurrection are entirely physical, yet he is not bound by the laws of space and time. Jesus’ life is no longer governed by physical and biological laws. In the Emmaus account, the risen Jesus is not at first recognised. But as faith and love become more refined, the risen Jesus is at last recognised in faith and love.

Veracity

Ratzinger comments:

The dialectic, which pertains to the nature of the Risen One, is presented quite clumsily in the narratives, and it is this that manifests their veracity. Had it been necessary to invent the resurrection, then all the emphasis would have been placed on full physicality, on immediate recognisability, and, perhaps, too, some special power would have been thought up as a distinguishing feature of the Risen Lord. But in the internal contradictions characteristic of all the accounts of what the apostles experienced in the mystical combination of otherness and identity, we see reflected a new form of encounter, one that from an apologetic standpoint may seem rather awkward but is all the more credible as a record of the experience.

Liturgy

The appearance of the resurrected Jesus to the two disciples walking to Emmaus has liturgical significance, the episode being akin to the Mass, where Jesus comes to us in the Liturgy of the Word, and also in the Liturgy of the Eucharist, blessing and breaking the bread, which is consumed by us in communion. The breaking of the bread symbolises the self-giving of the crucified Christ, the death of Christ on the Cross. At the centre of every Mass, the priest, acting in persona Christi, takes the bread, says the blessing, gives it to his disciples, saying “Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my body which shall be given up for you.” At the breaking of the bread, the two disciples who had walked from Jerusalem to Emmaus recognise Jesus. Only in the breaking of the bread does Jesus become truly visible. It is apparent from the Gospel accounts as a whole that the breaking of the bread is accompanied variously by looking up to heaven, by giving thanks and praise. The words and actions of Jesus at Emmaus are to be considered in the light of Jesus’ words and actions when he miraculously multiplied the loaves, and in the light of the New Testament accounts of the Last Supper.

Theology

The Emmaus episode has theological significance as the travellers, despite their misunderstanding of Jesus of Nazareth, despite their ignorance, despite their personal inadequacies, helped by Jesus’ explanation, understand the truth of scripture, the truth of Jesus Christ, triumphant over death. Love has triumphed over death. The tragic answer to man’s claim to autonomy, to self-sufficiency – typified by the fateful decision in the garden of Eden, and illustrated by the futile Tower of Babel resulting in chaos – is death. As humans we live and flourish, depending upon God, and upon one another.

Love Is Stronger than Death

The person may seek somehow to persist past death in a heroic fashion through achievement and fame (e.g. Alexander the Great, Napoleon) or, less spectacularly, through a numerous progeny. One cannot take one’s money with one! Naked one enters the world, and naked one leaves. Such tenuous aspirations to immortality always fail. By contrast, Jesus’ total love for men, which leads him to the Cross, is perfected in totally passing beyond, to the Father, and thereby, love becomes stronger than death. What seems to be a nice sounding platitude – love is stronger than death (Song of Solomon 8:6) – is true in the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

The late afternoon stroll to Emmaus encapsulates Christian faith and life.

The Lord Has Risen and Appeared to Simon

What the two disciples are told when they return to Jerusalem – “The Lord has risen indeed, and has appeared to Simon!” encapsulates the faith, the hope, and the life of the Church, and of all Christians.

Michael McAuley

3 April 2023