Saint Patrick was a gentleman,

Who, through strategy and stealth,

Drove all the snakes from Ireland:

Here’s a bumper to his health.

But not too many bumpers,

Lest we lose ourselves, and then

Forget the good Saint Patrick, And see the snakes again.

The legend of St Patrick driving all the snakes from Ireland is just that! By the time St Patrick arrived in Ireland, the snakes had long since gone! But if you want to argue about that, another day is required!

Irish Origins

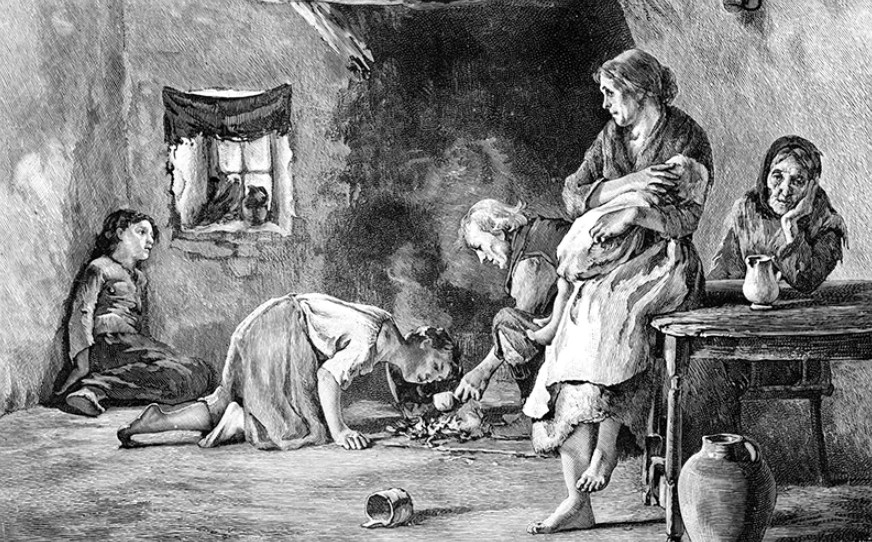

Of my family’s Irish peasant origins there can be no doubt. But our Irishness was always a little ambivalent, and second to being Australian. Perhaps there was a wish to forget. My forebears had little schooling and no money. They emigrated to South Australia following the Potato Famine (1845-49), when one million Irish died of starvation, and two million (by 1855) emigrated. This emigration continued for the rest of the 19th century. Starvation or emigration was the choice. My forebears came to South Australia rather than to the United States because they were very poor. They could get an assisted passage to South Australia. When Broken Hill opened up in the 1880’s some moved there.

Part of the reason the Irish wished to forget Ireland was because of the horror of the Potato Famine and the years following. They were traumatised by events in Ireland immediately prior to their departure for Australia.

No Going Back

My forebears left Hibernia, knowing there was no going back. There was nothing to go back to. There was no nostalgia for Ireland. There was no dwelling on past injustices. Their eyes were fixed ahead, never casting a glance in the rear-view mirror. They were aware they were a Catholic minority in Australia, and, buoyed by their Catholic faith, assisted by Catholic schools, were determined to get ahead, to give their children the best possible start in life.

St Patrick’s Day

My forebears all celebrated St Patrick’s Day. On St Patrick’s Day, surely the greatest day of the year (other than Easter and Christmas), one always wore some green. In Broken Hill even the petrol was dyed green. The St Patrick’s Day Race Committee was a big deal in Broken Hill.

St Patrick

Who was St Patrick? St Patrick’s dates are disputed, some have suggested 385-461. St Patrick was born in Roman Britain, the son of a deacon. He was captured by Celtic raiders at the age of 16 and taken as a slave to Ireland. Patrick was, for six years, a shepherd, looking after animals. He experienced a conversion to his Christian faith in Ireland. Patrick eventually escaped, and returned to Roman Britain. St Patrick had a vision of the Irish calling him back to Ireland. Patrick studied in France where he became a monk, and was ordained a priest, and a bishop. Eventually, Patrick returned to Ireland, where he experienced many difficulties bringing the Gospel to the pagan Celts.

Patrick is said to have used the shamrock to explain the Trinity. He was the first Bishop of Armagh, and Primate of Ireland, the founder of Christianity who converted Ireland from Celtic polytheism. St Patrick symbolises the very close relationship between Irish Celtic culture and Catholicism.

Culture

Catholicism is deeply embedded in Gaelic culture, even in the culture of those who reject the Church. It is to be found, more or less, in the traditions of hospitality, in singing, in dancing, in literature, in poetry, in sport, in art and architecture, in marriage and family life, in work and business, in law, in the respect given to persons, as well as the sense of community, in Irish humour.

Confessions

The deep spirituality of St Patrick is evident in his Confessions:

Thus I give untiring thanks to God who kept me faithful in the day of my temptation, so that today I may confidently offer my soul as a living sacrifice for Christ my Lord; who am I, Lord? or, rather, what is my calling? that you appeared to me in so great a divine quality, so that today among the barbarians I might constantly exalt and magnify your name in whatever place I should be, and not only in good fortune, but even in affliction? So that whatever befalls me, be it good or bad, I should accept it equally, and give thanks always to God who revealed to me that I might trust in him, implicitly and forever, and who will encourage me so that, ignorant, and in the last days, I may dare to undertake so devout and so wonderful a work; so that I might imitate one of those whom, once, long ago, the Lord already pre-ordained to be heralds of his Gospel to witness to all peoples to the ends of the earth. So are we seeing, and so it is fulfilled; behold, we are witnesses because the Gospel has been preached as far as the places beyond which no man lives.

Forebears

Many of my Irish immigrant forebears had big families. Some loved music. Some loved dancing. Some loved sport. All had a sense of humour. Some loved an argument. With some, it was hard to know what was fact, and what was fiction. Some drank to excess. Some gambled or ran illegal bookie operations. Some had little regard for the law.

No Irish Nationalists

There were no Irish nationalists in the family, no IRA supporters. Archbishop Mannix’s Irish nationalism won little support in Broken Hill. A common view was there had been too much violence and killing. The partition in 1922 of Ireland between north and south was barely discussed. Even in a Catholic school, with most of the teachers and students of Irish origin, my forebears learnt heaps about the British Empire, nothing about the Potato Famine, heaps about the great English writers, nothing about the Irish literary revival from the 1890’s.

Irish History

Irish history can be divided into different periods: pre-Celtic (from about 10,000 BC), Celtic (from about 500 BC), Irish monasticism (432-1171), Anglo Norman (1171-1534), Reformation (1534-1922), and Partition (1922 to present). These time periods are, to some extent, both arguable and arbitrary. The golden thread of Irish history is Catholicism, loyalty to the faith, in spite of persecution, in particular the attempt to force Protestantism on Catholic Ireland in the post Reformation era.

Celts

Humans lived in Ireland from about 10,000 BC. In the 500’s Celts come to Ireland. The Celts were a wild warrior people who could neither read nor write, but who loved poetry and stories, hard drinking and dancing. Palladius had previously been sent by Pope Celestine to the Gaels.

Irish Monasticism (432 – 1171)

In the 500’s, following the conversion of Ireland, Irish monasticism flourished. Irish missionary monks preserved classical Celtic culture, committed Celtic mythology and stories to writing, and evangelised Scotland, as well as modern France, Germany and northern Italy. The Irish missionary monks played a major part in the intellectual history of western Europe, preserving and propagating thought when it was almost lost. This is typified in the Book of Kells, created about 800 in an Irish monastery, containing the four Gospels illuminated with very beautiful depictions of Christ, and of Gospel scenes, which somehow survived the destruction of the Vikings, and, centuries later, of Cromwell’s army.

Vikings

In 795 Vikings from modern day Norway raided Ireland, beginning 200 years of violence, slavery and pillage. The Vikings established the city of Dublin on the Liffey river with an international slave market. In 1014 the Vikings (together with their Irish allies) were defeated by last High King of Ireland, Brian Boru, at Battle of Clontarf. Nevertheless, the Vikings remained, intermarrying with the local people, becoming indistinguishably Irish.

Anglo Normans (1171 – 1534)

In 1171 the English Norman Henry II, abetted by the then English Pope Adrian IV, landed at Waterford and declared himself Lord of Ireland. Yet beyond the Pale the native Irish survived. Thus began 750 years of English misrule. Catholic Ireland epitomised English imperialism at its worst, particularly after the English Tudors and their successors sought to impose Protestantism on the Catholic Irish. The Anglo Irish justified their actions, regarding the Irish as barbarians.

The 12th century was a time when Irish Catholicism drew closer to Rome, the distinctive Irish monastic tradition being drawn into the broader tradition of the western Church. In the 12th century and following, Irish monasticism was replaced by the monasticism of the broader Church, the Benedictines, the Cistercians, the Augustinians, the Franciscans, the Dominicans.

Reformation (1534 – 1921)

In 1534 Henry VIII broke from Rome. The Irish remained determinedly Catholic. They remained loyal to the Faith. In 1542 the Irish Parliament passed the Crown of Ireland Act which established a Kingdom of Ireland to be ruled by Henry VIII and his successors. Irish Catholics were subject to religious persecution involving death and imprisonment, deprivation of land, economic and political vassalage, being refused the right to provide even the most basic education to their children.

The English Tudors and their successors sought to impose the Protestant Reformation on the unwilling Irish, justifying their actions by a “civilising mission”. The established Church of Ireland acquired most of the significant religious buildings, for instance, St Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin. In 1607 the Plantation of Ulster was begun with Scottish Presbyterians, an attempt to redress the numerical balance in Ireland between Catholics and Protestants in favour of Protestants. In 1649 Oliver Cromwell and an army arrived in Ireland, determined to enforce the Protestant ascendancy, massacring large numbers of Irish civilians, destroying the infrastructure of country. In 1681 Archbishop Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, Primate of All Ireland, successor of St Patrick, was hung, drawn and quartered in London.

In the 1700’s the Penal Laws directed against the practice of the Catholic Faith were at their height. Irish priests were outlawed. Irish priests were hunted down by bloodhounds and armed soldiers. They were thrown into prison for the crime of saying Mass at “Mass-rocks”. Mass was said hurriedly in the fields for fear of discovery. Often priests were hung, drawn, and quartered. Irish Catholic children were deprived of schooling except at illegal hedge schools. Effectively Catholics were deprived of workable portions of land, left at the mercy of often absentee landlords, and their agents. The effect of the Penal Laws was to bring priest and people together in suffering.

A Modest Proposal

Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels, was appointed Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin in 1713. Swift saw firsthand the results of English tyranny in Ireland. Swift wrote A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country. Swift, tongue in cheek, urged that Irish children be slaughtered to provide a delicacy for the dining tables of London. Swift’s point was there was little practical difference between the inhumanity which allowed Irish children to live in extreme poverty, often starving, and killing them to enhance the cuisine of English diners! Between 1739 and 1741, 400,000 Irish died of starvation. By contrast the concentration of money and power made the Protestant Ascendancy. In 1742 Handel’s Messiah was played for the first time. There were two Irelands.

In 1801, the Union of Great Britain and Ireland came into force with a resulting Irish (initially Protestant) voice in the UK parliament. In 1829 the UK parliament passed a law for Catholic “emancipation”. This did little to undo centuries of economic discrimination which had dispossessed Catholics of land, and prevented them from earning a decent living.

Potato Famine

In 1845-49 the potato crop failed with the resulting Great Famine. Government relief for starving Catholics was slight and grudging. Previous dispossession of land over some 250 years had deprived Catholic peasants of land. Land ownership was largely concentrated in the hands of Protestant landowners. Catholics were tenants renting ever smaller lots of land their families had previously owned. Ever smaller plots of land made it difficult for Irish peasants to plant a variety of crops, and made for reliance on a single crop. The potato was a particularly nutritious crop, but the population was over-reliant on it. The inability of tenants to pay rents provided an opportunity for absentee landlords to evict tenants, and destroy their homes. The policy of the British government was genocidal, influenced by contempt for the ordinary Irish, and by a laissez-faire ideology. The British Government had the means to prevent mass starvation, but chose not to do so. At this time Great Britain was the richest country on earth. Throughout the Potato Famine Ireland was a major exporter of food, food that could have been used to prevent starvation at home. Wheat, corn, fish, cattle, sufficient to prevent starvation, were exported.

One million Irish died of starvation and associated disease. By 1855 two million Irish had emigrated. Before the Potato Famine the population of Ireland was 8 million. By 1900 the population of Ireland was 4 million. The effects of the Potato Famine continued in Ireland for the rest of the 19th century and into the 20th century, with constant emigration from this land of horrors, for the majority, who were both poor and Catholic.

Our Lady of Knock

In 1879 Our Lady appeared at Knock, still a place of pilgrimage today, an icon of the deep devotion of the Irish to the Mother of God. Was this a kiss, an embrace, full of affection from our Blessed Mother to the Irish who had remained loyal to the Faith?

Gaelic Revival

In 1890 began the Gaelic revival. The Gaelic literary and artistic revival, featured writers such George Bernard Shaw, WB Yeats, Sean O’Casey, James Joyce, J M Synge, Oscar Wilde – some hostile to aspects of traditional Irish culture, some idealising the culture of the pagan Celts. In 1904 the Abbey Theatre had been founded in Dublin. About the same time there was a Gaelic sporting revival with renewed interest in traditional Irish sports such as Gaelic football and hurling.

In 1914 legislation was passed for Irish Home Rule, but its implementation was deferred for the duration of World War I. In 1916 there was an armed rising in Dublin in which rebels occupied the GPO, but failed to elicit rebellion elsewhere in Ireland. In 1918-21 Michael Collins and Eammon de Valera led the war of Irish independence.

Partition (1921 to now)

In 1921 Michael Collins signed the Anglo Irish Treaty providing for Northern Ireland to remain as part of Great Britain, effectively partitioning Ireland between the Protestant north and the Catholic south. From 1922-23 there was a civil war between those who accepted partition of northern majority Protestant Ireland from the Catholic south, and those who rejected partition. In 1936 Ireland became a Republic.

St Patrick’s Breastplate

The rejection of the rear view of Irish history by my forebears (like so many other Irish Australian families) was both an attempt to forget the trauma of the Great Famine, and an application of the perspective – forgive and get on with things. Murderous zealotry, even in response to tyranny and oppression, cannot be justified-and is at odds with the best of Gaelic culture. Violence is no solution to human problems. Now is what matters. There are better things to do than dwell on past injustices.

The challenge for modern Ireland, is that paganism is returning. Ireland needs new Patricks who will re-evangelise the Irish, and the culture of Ireland. The prayer of St Patrick, St Patrick’s Breastplate, puts all this in perspective:

Christ before me, Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ at my right, Christ at my left, Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down, Christ when I arise, Christ in the heart of everyone who thinks of me, Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks to me, Christ in the eye of everyone who sees me, Christ in the ear of everyone who hears me.

Michael McAuley