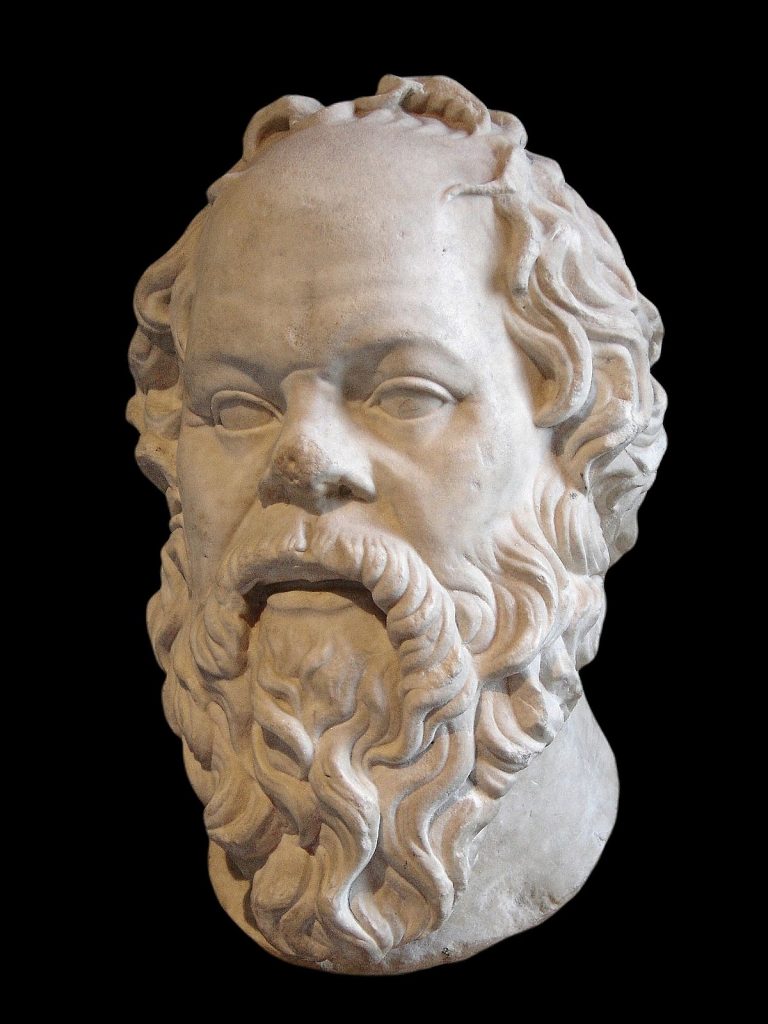

Socrates (470-399 BC), although referred to by various writers (Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon, Aristophanes etc), is a mysterious fellow. The various ancient writers present Socrates, each from their own perspective. Socrates himself wrote nothing, but wandered around Athens, gathering together young men, who observed, or took part in the dialogues, in which Socrates exposed the falsity and meretriciousness of the certitudes of the Athenian elite.

It is difficult to distinguish between the historical Socrates and the presentation of the particular writer, who refers to Socrates. For instance, Aristophanes’ attack on Socrates in the play, The Clouds, uses Socrates as a convenient figure for satire, but presents Socrates as a sophist, something Socrates was not.

Plato

Plato, particularly in his middle and later dialogues, arguably presents Socrates as a way of presenting his own thought, rather than as a way of presenting the thought of the historical Socrates. Moreover, the dialogue format makes it difficult to discern Socrates’ conclusions, as opposed to the questions with which he grapples. Finally, Socrates is a person of humour. It is not always easy to discern what is seriously proposed, as opposed to Socrates engaging in elaborate leg-pulling. For instance, what is one to make of Socrates’ proposal following conviction that an appropriate penalty be free meals for life at public expense? Arguably, Socrates is being ironic and serious at the same time: he is saying that he has been a public benefactor – and therefore deserves a reward. What is one to make of Plato’s Republic? Is it seriously meant? or tongue in cheek, a literary device for dealing with many different aspects of human life on which there are diverse opinions? One must distinguish between the historical Socrates and the Platonic Socrates. We are constantly presented, in Plato’s dialogues, where Socrates is the protagonist, with the Socratic Question: who was Socrates? what did he think? Many times, there is no easy answer.

Apology

Nevertheless, it seems to me that Plato’s Apology, one of Plato’s early works, written close in time to Socrates’ trial and death, is as good an account of the historical Socrates as one can get.

Kangaroo Court

Given the limits of space, I confine myself to what Socrates had to say in the third part of the Apology, following his conviction by the Athenian jury, and following the imposition of the death penalty. Needless to say, the trial was unjust, as was the conviction, and sentence. The charges – disbelief in the gods of Athens, and corruption of the youth – were motivated by the malice of Socrates’ accusers, and should never have been brought. Socrates’ trial, conviction and sentence is an illustration of that venerable institution, the kangaroo court.

The religious and civil trials which culminated in the condemnation of Jesus of Nazareth were unjust trials. The trials of Jesus of Nazareth, and of Socrates, have similarities, but important differences – the most important being, as regards the accused, Socrates, that he was wise, but as regards Jesus of Nazareth, that he is God Incarnate, Wisdom itself. The trial of Socrates, and the trials of Jesus of Nazareth, at the beginning of our civilisation, are a reminder that not every allegation is true, not every allegation ought be pursued, judges and juries do not always get it right, not every trial is just.

Key portions of Socrates’ speech following conviction and sentence are:

Escape from Doing Wrong

- In a court of law, just as in warfare, neither I nor any other ought to use his wits to escape death by any means.

- But I suggest, gentlemen, that the difficulty is not so much to escape death; the real difficulty is to escape from doing wrong, which is far more fleet of foot. In this present instance, I the slow old man, have been overtaken by the slower of the two, but my accusers, who are clever and quick, have been overtaken by the faster: by iniquity. When I leave this court, I shall go way condemned by you to death, but [my accusers] will go away convicted by Truth herself of depravity and wickedness.

- If you expect to stop denunciation of your wrong way of life by putting people to death, there is something amiss with your reasoning. This way of escape is neither possible nor creditable; the best and easiest way is not to stop the mouths of others, but to make yourselves as good as you can.

Death as Annihilation

- Death is one of two things. Either it is annihilation, and the dead have no consciousness of anything; or, as we are told, it is really a change: a migration of the soul from this place to another.

- Now if there is no consciousness but only a dreamless sleep, death must be a marvellous gain.

Life After Death

- If, on the other hand, death is a removal from here to some other place, and if what we are told is true, that all the dead are there, what greater blessing could there be than this, gentlemen? If on arrival in the other world, beyond the reach of our so-called justice, one will find there the true judges who are said to preside in those courts, Minos and Rhadamanthys and Aeacus and Triptolemus and all those other half divinities who were upright in their earthly life, would that be an unrewarding journey? Put it in this way: how much would one of you give to meet Orpheus and Musaeus, Hesiod and Homer?

Nothing Can Harm a Good Person

- You too, gentleman of the jury, must look forward to death with confidence, and fix your minds on this one belief, which is certain: that nothing can harm a good person either in life or after death, his fortunes are not a matter of indifference to the gods.

- I am quite clear that the time has come when it was better for me to die and be released from my distractions.

Bear No Grudge

- For my own part I bear no grudge at all against those who condemn me and accuse me, although it was not with this kind intention that they did so, but because they thought they were hurting me; and that is culpable of them.

Goodness Above All

- However, I ask them to grant me one favour. When my sons grow up, gentlemen, if you think that they are putting money or anything else before goodness, take your revenge by plaguing them as I plagued you; and if they fancy themselves for no reason, you must scold them just as I scolded you, for neglecting the important things and thinking that they are good for something when they are good for nothing. If you do this, I shall have had justice at your hands, both I myself and my children.

Now it is time that we were going, I to die and you to live; but which of us has the happier prospect is unknown to anyone but God.

Life After Death

While there are important differences between the thought of Socrates expressed in the Apology, and the teaching of the Church, there are similarities. Socrates believes in immortality. Socrates also urges a life of virtue as opposed to striving after sensible pleasures, material possessions, “success”.

Holy Souls

On 2 November each year the Church remembers the Holy Souls in Purgatory, a recognition and acknowledgment of hope. This is a recognition of what the Church refers to as the Four Last Things – death, judgment, heaven, hell. The Four Last Things is a phrase which seeks to sum up a very nuanced and complex understanding, expressed, for instance, in the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

Particular Judgment

- Every man receives his eternal recompense in his immortal soul from the moment of his death in a particular judgment by Christ, the judge of the living and the dead.

- “We believe that the souls of all who die in Christ’s grace . . . are the People of God beyond death. On the day of resurrection, death will be definitively conquered, when these souls will be reunited with their bodies”: Pope St Paul VI

Paradise

- “We believe that the multitude of those gathered around Jesus and Mary in Paradise forms the Church of heaven, where in eternal blessedness they see God as he is and where they are also, to various degrees, associated with the holy angels in the divine governance exercised by Christ in glory, by interceding for us and helping our weakness by their fraternal concern”: Pope St Paul VI

Purgatory

- Those who die in God’s grace and friendship imperfectly purified, although they are assured of their eternal salvation, undergo a purification after death, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of God.

Communion of Saints

- By virtue of the “communion of saints”, the Church commends the dead to God’s mercy and offers her prayers, especially the holy sacrifice of the Eucharist, on their behalf.

Hell

- Following the example of Christ, the Church warns the faithful of the “sad and lamentable reality of eternal death”, also called “hell.”

- Hell’s principal punishment consists of eternal separation from God in whom alone man can have the life and happiness for which he was created and for which he longs.

God Desires All to Be Saved

- The Church prays that no one should be lost: “Lord, let me never be parted from you.” If it is true that no one can save himself, it is also true that God “desires all to be saved”, and that for him “all things are possible”.

General Judgment

- “The holy Roman Church firmly believes and confesses that on the Day of Judgment all men will appear in their own bodies before Christ’s tribunal to render an account of their own deeds” : Council of Lyons

Kingdom of God

- At the end of time, the Kingdom of God will come in its fullness. Then the just will reign with Christ forever, glorified in body and soul, and the material universe itself will be transformed. God will then be “all in all”, in eternal life.

The liturgical readings from All Holy Souls’ Day celebrated on 2 November epitomise the Church’s understanding of that human reality we all confront – death.

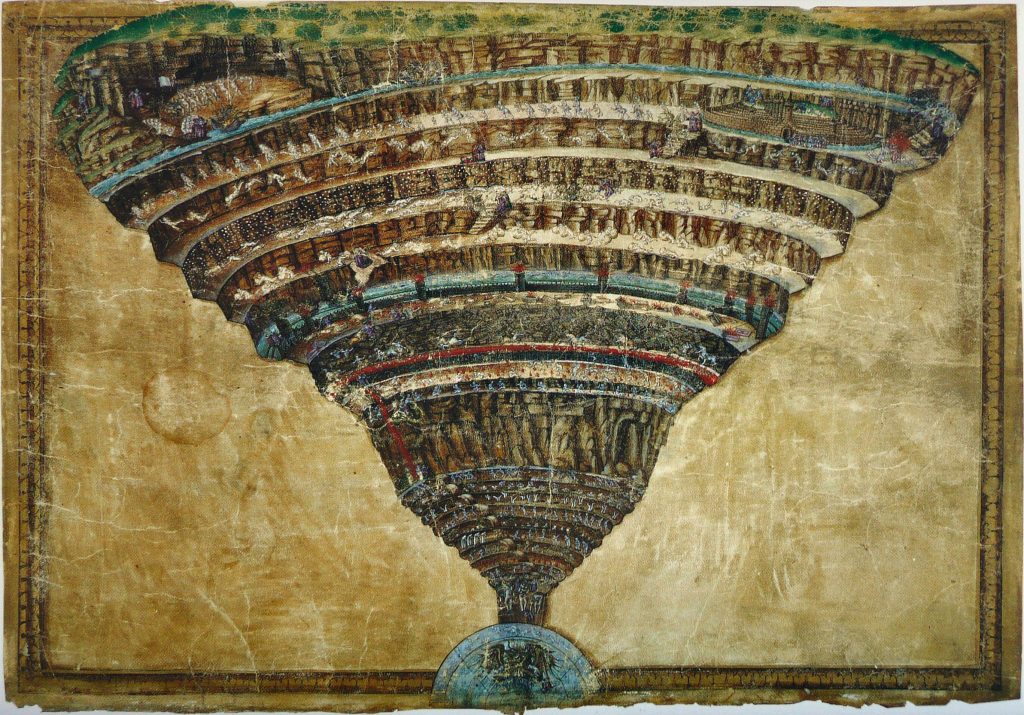

Dante’s Divine Comedy

The literary presentation of the Church’s understanding of what follows death is Dante’s Divine Comedy. Dante’s journey through hell, purgatory and heaven comes at a mid-point in life when Dante has the opportunity to turn from a life of earthly pleasure and success to what Socrates urges as a life of virtue.

Death, judgement, heaven and hell, are mysterious realities which we can never fully grasp. These mysterious realities should impel us to lead a life of virtue.

Plato and Aristotle

Striving after virtue is a feature of the thought of Socrates and his most famous pupils, Plato and Aristotle. Plato had known Socrates personally, and, for a time, Aristotle was a pupil of Plato.

Socrates and Jesus of Nazareth

Socrates lived four hundred years before Jesus of Nazareth. Despite the suggestions of some, there is no evidence that Socrates (nor his alter ego, Plato, in the middle and later dialogues) had any familiarity with what became the Hebrew Bible.

Both Jesus of Nazareth and Socrates are important and influential figures at the beginning of our civilization. Jesus of Nazareth and Socrates have much in common – but clearly there are important differences. The nature of those differences is a matter for another day.

Michael McAuley

24 October 2022

Chronology

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 750 – 700 BC | Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey composed. |

| 490 BC | Persians launch naval attack against Greek cities. Greek victory in Battle of Marathon. |

| 480 BC | Persians under Xerxes invade Greece again. Athenians are compelled to abandon their city and take to the seas, but the size of Greek victory in Battle of Salamis. |

| 479 BC | Defeat of Persian Army at Plataea and of Persian Navy at Mycale. Construction of Athens’ defensive walls (Long Walls). |

| 478 – 323 BC | Classical period of Hellenic history. |

| 478 – 404 BC | Establishment of Delian League out of which grew Athenian Empire. |

| 470 BC | Birth of Socrates. |

| 461 – 429 BC | Political prominence of Pericles, controlling Athenian policy in turning the Delian League into an Athenian Empire. |

| 460 – 445 BC | First Peloponnesian War (Sparta v Athens) begins, chronicled by Thucydides. |

| 447 BC | Construction of Parthenon begins. |

| 445 BC | Long Walls are completed. |

| 431 – 404 BC | Second Peloponnesian War (Sparta v Athens) |

| 430 – 429 BC | Plague in Athens. |

| 430 BC | Annual invasions of Attica area surrounding Athens begin. Plague devastates Athens. |

| 429 BC | Death of Pericles. |

| 428 BC | Birth of Plato. |

| 423 BC | Performance of Aristophanes’ The Clouds. |

| 415 BC | Athens launches staggeringly ambitious, and ultimately catastrophic invasion of Sicily. |

| 412 BC | Mass revolt of Athenians subjects and allies. |

| 411 BC | Oligarchy of Four Hundred in Athens, and thus democracy is overthrown. |

| 404 BC | End of Peloponnesian War, surrender of Athens, destruction of Long Walls. Sparta installs puppet regime in Athens, known as the Thirty Tyrants. |

| 404 – 403 BC | Oligarchy of Thirty in Athens. |

| 404 – 371 BC | Spartan Hegemony of Greece. |

| 403 BC | Restoration of democracy in Athens. |

| 399 BC | Trial, conviction and execution of Socrates in Athens. |

| 395 – 393 BC | Rebuilding of Long Walls in Athens. |

| 386 BC | Plato founds academy in Athens. |

| 384 BC | Birth of Aristotle. |

| 378 BC | Second Athenian League established. |

| 359 – 336 BC | Reign of Philip II of Macedonia. |

| 356 BC | Birth of Alexander the Great |

| 351 BC | Orator, Demosthenes of Athens, beings his campaign warning of the dangers posed by Phillip II of Macedon. |

| 347 BC | Death of Plato. |

| 339 – 168 BC | Hellenistic Age: Greek Empires of Macedonian Kings. |

| 338 BC | Battle of Chaeronea (Phillip II of Macedonia defeats the Greeks). Alexander the Great of Macedon, son of Phillip II, visits Athens. |

| 338 – 337 BC | League of Corinth created by Phillip II of Macedon by which the Macedonian Hegemony of Greece was assured. The Greeks were bound together in a ‘common peace’ to deter revolt or uprising against Macedon. |

| 336 BC | Assassination of Phillip II. |

| 336 – 323 BC | Reign of Alexander the Great. |

| 335 BC | Aristotle founds Lyceum in Athens. |

| 334 BC | Alexander the Great begins his campaign to conquer Asia. |

| 324 – 323 BC | Alexander the Great in Asia. |

| 323 BC | Death of Alexander the Great. |

| 322 BC | Death of Aristotle. |

| 146 BC | Roman annexation of Greece. |