My Year 2 teacher, drawing on the Green Catechism, itself a worthy contender for inclusion in any list of “great books”, at least of Christian literature, prepared me admirably for my first Confession, and First Holy Communion. Sister Mary Esther is long since forgotten except perhaps by a few old timers, including myself. Like so many nuns who, in the 19th and 20th centuries, staffed Australian Catholic schools, she deserves to be remembered, as drawing the transcendent out of the ordinariness of daily life. As well as introducing me in a systematic way to the Faith, Sister Mary Esther introduced me to the great ideas.

GREAT IDEAS

The perennial or great ideas we each have to confront, no matter who we are, or when, or where we live. For instance – happiness, family, law, justice, love, tyranny, slavery, wisdom, progress, war, duty, immortality, patriotism, language, virtue, science, education, metaphysics, pleasure, freedom, reason, woman, punishment, logic, argument, rhetoric, freedom, slavery. The great writers give different and conflicting answers to the perennial questions to which everyone must respond. Reading the great writers is a preliminary to faith because of the questions the great writers raise. The great writers raise questions which we each have to answer explicitly or implicitly, simply by living – regardless of whether we are capable of articulating a response in words.

GREAT WRITERS

Amongst the great writers who introduce us to the great ideas, who, more or less, evoke the universal, in the particular are Homer, Sophocles, Thucydides, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, St Augustine, St Thomas Aquinas, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Calvin, Desiderius Erasmus, William Shakespeare, John Milton, Michel de Montaigne, Galileo Galilei, Miguel de Cervantes, Blaise Pascal, John Locke, David Hume, the American Founding Fathers, Alex de Tocqueville, Adam Smith, Immanuel, Kant, Edward Gibbon, John Stuart Mill, Charles Dickens, John Henry Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Soren Kiekegaard, Karl Marx, Leo Tolstoy, Frederick Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, John Maynard Keynes, Ernest, George Orwell, Karl Barth …

Some of these great writers did not get it right, some in very big ways (e.g. John Calvin, David Hume, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Frederick Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud). Some of these great writers are Christian, some are not. Yet even the most benighted had some valuable insights. Even those who get it seriously wrong, provide an opportunity to explore why they get it wrong, and to refine our understanding of the truth. Because of the perennial issues they deal with, and the manner in which they write, they deserve to be regarded as amongst the great writers. These great writers are not out of the past but speak to us today. These great writers wrote for and are accessible by the non-specialist.

ST AUGUSTINE

A step in St Augustine’s conversion was reading a lost work of Cicero, Hortensius, which raised philosophical issues which he had to confront on the road to faith. Nothing that is really beautiful, really good, really true, can be at odds with, or foreign to faith. Faith and reason can never conflict. According to St Augustine, reading Hortensius, altered his wishes and desires. Suddenly, every vain hope became worthless to him, and Augustine yearned with unbelievable ardour of heart for the immortality of wisdom.

ALIENATION

The truth, even if partial, unexpectedly found in some unlikely thinker, is to be recognised, and, if necessary purified, and embraced. For instance, St John Paul II did this in his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis (1979), considering the Marxist concept of “alienation”. From 1945 to 1978, when St John Paul II was elected Pope, he had to deal with communists on a daily basis, communists who were determined to destroy the Church, communists whose policies in Poland were destructive of both personal good, and of the common good. No doubt the future St John Paul II felt the emotional response to dismiss Marxism root and branch, disregarding whatever truth is to be found in Marxism. Yet St John Paul II recognised the truth of the Marxist concept of “alienation”, purified it, and embraced it:

The man of today seems ever to be under threat from what he produces, that is to say from the result of the work of hís hands and, even more so, of the work of his intellect and the tendencies of his will. All too soon, and often in an unforeseeable way, what this manifold activity of man yields is not only subjected to “alienation“, in the sense that it is simply taken away from the person who produces it, but rather it turns against man himself, at least in part, through the indirect consequences of its effects returning on himself. It is or can be directed against him… Man therefore lives increasingly in fear. He is afraid that what he produces-not all of it, of course, or even most of it, but part of it and precisely that part that contains a special share of his genius and initiative-can radically turn against himself.

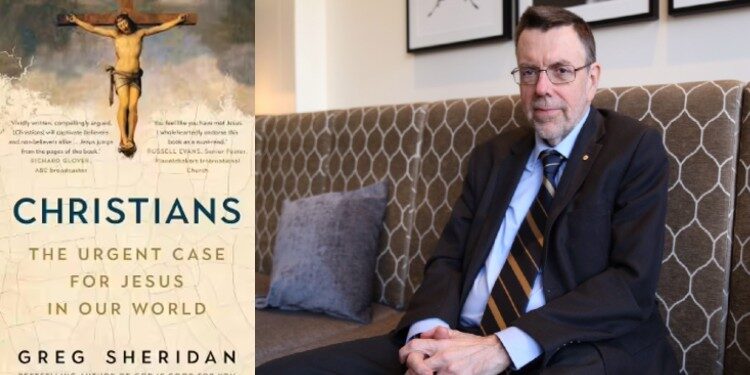

GREG SHERIDAN

Greg Sheridan, in his 2021 The Urgent Case for Jesus in Our World, comments on the anti-Christian nature of contemporary popular culture. The grand old days of Spencer Tracey and Gregory Peck playing lantern-jawed, physically courageous, morally heroic Catholic priests, or Walter Pidgeon, a fine Protestant minister who is the very embodiment of integrity and wisdom in How was My Valley – that is all gone. This is a tragedy for popular culture. First, Christianity is true, and art should see the truth, even if, as so often, it decides to argue with the truth. Better to argue with something worth arguing with than nothing at all. Second, Christianity offers the deepest sense of hope in the human condition, and art and culture should see hope. Third, art which ignores the religious dimensions in humanity cuts itself off from a huge swathe of human experience and reflection. It isolates itself from the great rivers of human sentiment that run across the ages. Fourth, the Christian perspective projects depth and meaning into human affairs.

There need to be Christian journalists, novelists, poets, playwrights, film directors, actors, and shock-jocks. We cannot abandon the world, but must win the world for Christ. But winning the world for Christ is not proselytism, but helping others to see the transcendent, the beautiful, the good and the true, in the particularity of things.

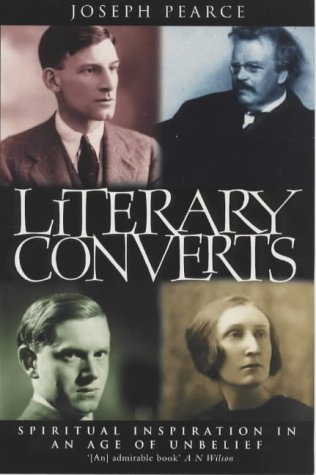

LITERARY CONVERTS

In Literary Converts (1999) Joseph Pearce outlines the story of a series of English intellectuals who, in the twentieth century, converted to Christianity, in many cases to Catholicism. Chesterton’s ‘coming out’ as a Christian had an effect, similar in its influence to Newman’s equally candid confession of orthodoxy. In many ways, Chesterton’s ‘coming out’ heralded a Christian literary revival which, throughout the twentieth century, represented an evocative artistic and intellectual response to the prevailing agnosticism of the age. Taken as a whole, the network of minds, identified by Joseph Pearce, represent a Christian response to the age of unbelief. This response produced some of the century’s great literary masterpieces and stands as a lasting testament to the creative power of faith.

Taking a somewhat wider cast than Joseph Pearce, one can identify a series of Christian intellectuals, not all Catholic, who have contributed greatly to English intellectual culture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

John Henry Newman (1801 – 1890)

- Newman was one of the protagonists of the Oxford Movement, which sought to revive the Anglican Church. Newman crossed the Tiber in 1845. In 1847 Newman was ordained a priest of the Oratory. In 1879 Pope Leo XIII appointed Newman a Cardinal. Amongst his best-known writings are The Idea of a University, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine, and The Dream of Gerontius. Newman’s theology influenced the Second Vatican Council.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89)

- Hopkins was received into the Catholic Church in 1866 by then Fr John Henry Newman. He joined the Jesuits, was ordained a priest, and spent his life teaching. The greatness of Hopkins’ innovative poetry was not recognised until after his death. Hopkins’ thought is suffused with the transcendental:

To lift up the hands in prayer gives God glory, but a man with a dungfork in his hand, a woman with a slop pail, give Him glory, too. God is so great that all things give Him glory if you mean that they should.

Illustrative of Hopkins’ poetry, but relatively accessible, is God’s Grandeur:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Francis Thompson (1859 – 1907)

- Francis Thompson was a homeless person, a drug addict, psychiatrically ill – and one of England’s greatest English poets. Francis Thompson’s The Hound of Heaven, the first fifteen verses of which I set out below display his profound mystical understanding:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways;

Of my own mind; and in the midst of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.

Up vistaed hopes I sped;

And shot precipitated,

Adown titanic glooms of chasmed fears,

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

But with unhurrying chase,

And unperturbed pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

They beat -and a Voice beat,

More instant than the Feet –

“All things betray thee, who betrayest Me”.

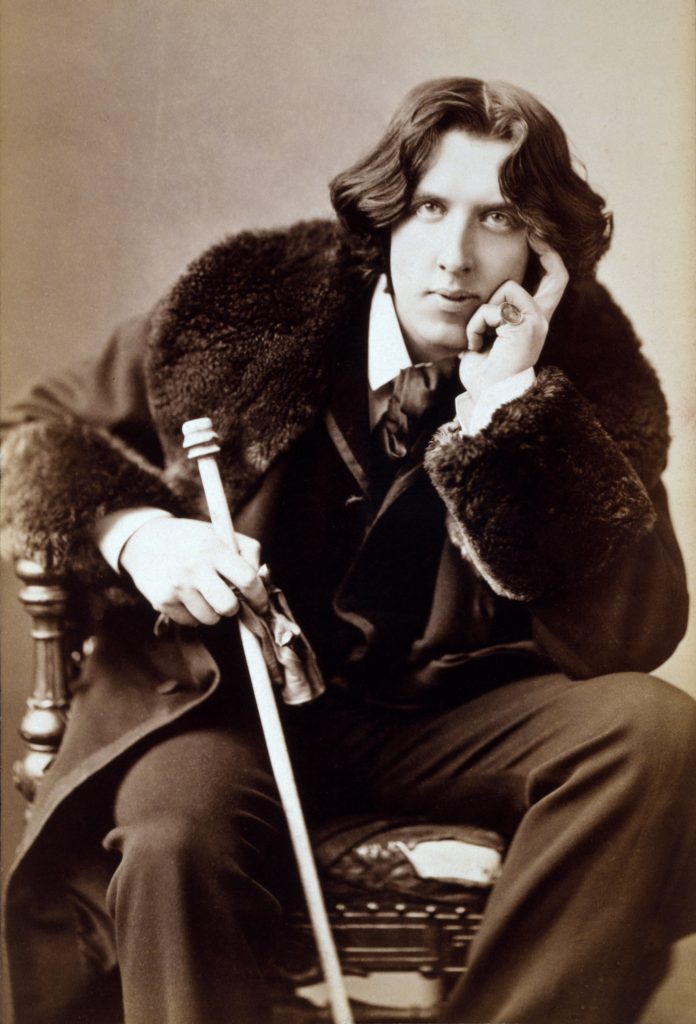

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

Oscar Wilde repented and converted on his deathbed. As a young man, Wilde had been attracted to Catholicism – and this attraction can be read in his writings – not least Wilde’s fairy stories for children, and even The Picture of Dorian Gray, Salome, De Profundis, and The Ballad of Reading Gaol, where one can see the tortured path that led to Rome. Strangely, both Wildes’ great foils – the Marquis of Queensbury, and his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, converted before their deaths.

R H Benson (1871 – 1914)

- R H Benson was the youngest son of the then Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1895 he was ordained a priest of the Church of England. In 1903 he was received into the Catholic Church. In 1904 Benson was ordained a Catholic priest. Benson wrote children’s stories, historical fiction, and horror stories, and a prophetic novel Lord of the World. Benson was instrumental in many other conversions.

Ronald Knox (1888 – 1957)

- Ronald Knox was the son of an Anglican bishop. He converted in 1917, and was ordained a Catholic priest in 1918. Knox singlehandedly translated the Latin Vulgate into English, what became known as the Knox Bible. Knox was, for many years, Chaplain at Oxford University. He is well known for his Ten Rules For Detective Fiction, as well as his satire, for instance, suggesting that the true author of one of Tennyson’s poems was, in fact, Queen Victoria!

Christopher Dawson (1889 – 1970)

- Christopher Dawson was a historian. He became a Catholic in 1909. Dawson argued that the so-called Middle Ages were significant in the making of modern Europe, that the medieval Catholic Church was essential to the rise of modern civilisation.

G K Chesterton (1874-1936)

- G K Chesterton wrote much of great value before he crossed the Tiber in 1922. Amongst Chesterton’s writings are the Father Brown Detective Stories, Orthodoxy, The Everlasting Man, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study, The Man Who Was Thursday, and The Napoleon of Notting Hill, as well as a book on St Thomas Aquinas. Chesterton’s Hymn, O God of Earth and Altar, is a summary of his thought.

Hilaire Belloc (1870 – 1953)

- Hilaire Belloc wrote Cautionary Tales for Children including Jim, who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion, and Matilda, who told lies and was burned to death. Cautionary Tales for Children are essential reading for a happy childhood.

T S Eliot (1885 – 1965)

- T S Eliot was an American by birth, but spent most of his life living in England. T S Eliot became an Anglo-Catholic. Eliot is well known for his poetry including The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock, The Waste Land, The Hollow Men, and Ash Wednesday. Elliot is an accomplished dramatist, perhaps best known for Murder in the Cathedral. Like C S Lewis, why Eliot never became a Catholic is a profound mystery.

Dorothy Sayers (1893 – 1957)

- Dorothy Sayers was an Anglo-Catholic. Sayers translated Dante’s Divine Comedy into English. Sayers wrote The Lord Peter Wimsey Series, as well as various religious works including The Mind of the Matter, Creed or Chaos? and The Man Born to be King. It is a mystery why she too never became a Catholic.

Evelyn Waugh (1903 – 1966)

- Evelyn Waugh, like Graham Greene, was one of the greatest English novelists of the 20th century. Amongst his best novels are Brideshead Revisited, Officers and Gentleman, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, and Love Among the Ruins.

Graham Greene (1904 – 1991)

- Graham Greene, in his later years called himself a “Catholic agnostic.” Despite a complicated life, Greene, as he grew older, returned to the Sacraments. Graham Greene is one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century. Amongst Graham Greene’s novels are Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter, The End of the Affair, and Our Man in Havana. Greene converted to Catholicism in 1926.

Frederick Copleston (1907 – 1984)

- Frederick Copleston converted to Catholicism at the age of 18 and later became a Jesuit priest. Copleston came from an old English family, the antiquity of which is illustrated by the ditty:

Crocker, Cruwys, and Coplestone,

When the Conqueror came were at home.

Copleston’s multivolume History of Philosophy is a classic.Written originally for seminarians, it is a fair-minded consideration of Western philosophy from the Greeks to the present day. Copleston became well known in 1948 for his BBC debate with Bertrand Russell on the existence of God.

Frank Sheed (1897 – 1981)

- Frank Sheed was an Australian lawyer who wrote To Know Christ Jesus, Theology for Beginners, and Theology and Sanity. Frank Sheed’s writings, possessed of a timeless quality, are well worth reading today.

E F Schumacher (1911 – 1977)

- E F Schumacher was a German English economist, the author of Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered. Schumacher is a critic of modern industrial society.

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903 – 1990)

- Malcolm Muggeridge is an English journalist who converted in his eighties, influenced by Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Amongst his writings are Tread Softly for You Tread On My Jokes, and Something Beautiful for God.

Elizabeth Anscombe (1919 – 1981)

- Elizabeth Anscombe was an English philosopher whose work on ethics is of enduring value.

C S Lewis (1898 – 1963)

- C S Lewis was an academic at Oxford and at Cambridge. He wrote prolifically, including for children The Chronicles of Narnia, as well as science fiction, The Space Trilogy, and theological pieces including The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, Miracles, and The Problem of Pain.

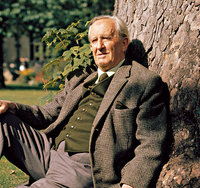

JRR Tolkien (1872 – 1973)

- JRR Tolkien was a professor of Ango-Saxon literature at Oxford University where he became a good friend of C S Lewis. Tolkien’s best-known works are The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings, though his short stories including Leaf by Niggle, Tom Bombadil, Smith of Wotton Manor, and Farmer Giles of Ham, are well worth reading. Tolkien converted to Catholicism as a boy, at the same time as his mother, who shortly after died. Tolkien’s writing, replete with allusions, some clear, others less clear, is not ostensibly Catholic, and yet most profoundly Catholic. Tolkien has a perennial quality which will cause his writings to persist in popularity after many others have been forgotten.

These writers were often friends, helping and influencing each other. The writing of each must be assessed piece by piece. There is a lifetime of reading here, not only for ourselves, but for our friends, for our children, for our grandchildren. Without such reading, our culture, our understanding of beauty, goodness and truth, will be less, or non-existent. The significance of these writers is not simply that they became Christian, like members of a gang, a club, a football team or, more depressingly, a political party, but that, through their conversion, they became better writers, more attuned to the universal, in all the particularity of daily life.

THOSE WHO WEAR THE COLOURS BUT DO NOT PLAY THE GAME

There are some who wear the colours, but who do not play the game, having nothing in their writing, of transcendence in particularity. These are the writers whose work will soon be forgotten not long after it is written, however numerous their sales at the time of publication. These writers do not engage in what the American philosopher Mortimer J Adler has referred to as the Great Conversation, or do so superficially, failing to engage with the issues which confront each of us, no matter when or where we live, failing to seek out the transcendent in the particularity of daily life, failing to engage with the great writers who went before, failing to write in such a way as to engage with those who will follow.

BEAUTIFUL, GOOD, TRUE

By contrast, in the writing of the great writers, we find the universal in the particular – as opposed to the banality, the grossness, the dreariness, the debauchery, the pessimism, the coarseness, the degradation, of so much that passes as literature for an instant, soon forgotten, because it has nothing of the universal in the particular, because it fails to speak to all, in every place, in every time, because it has little of beauty, goodness, truth. For all great literature, whatever its particularity, has at least echoes, flashes, glimpses, of the beautiful, the good, the true.

The greatest beauty, the greatest drama, the greatest truth, is to be found in the particularity of a grim suburban church in some black industrial centre, in a refugee camp populated by thousands of desperates, in a rarely visited country chapel, where a priest celebrates Mass, united with the sacrifice of Jesus of Nazareth on Calvary some 2000 years ago. There – is beauty, there – is goodness, there – is truth – of which the great artists, the great dramatists, the great writers have but a glimpse. Sister Mary Esther understood that nothing which is beautiful, nothing which is good, nothing which is true, is to be discarded – but to be accepted, purified and transformed.

Michael McAuley

1 October 2021