William Roper’s The Life of Sir Thomas More is More’s first (and arguably best) biography. It was written by William Roper in the mid-16th century, well after More’s judicial murder in 1535 at the behest of Henry VIII.

Roper’s More is a warm, engaging person, sensitive to others, the sort of person one wants to be with; brilliant but indifferent to riches, power, the ‘good life’; learned but carrying his learning lightly; self-effacing, yet realistic and shrewd in his judgments; not holding grudges, forgetful of slights, and of wrongs, at all times speaking well of others, devoid of hatred, cheerful to the end; supernatural in his perspective, prayerful, loving God and all those with whom he comes in contact.

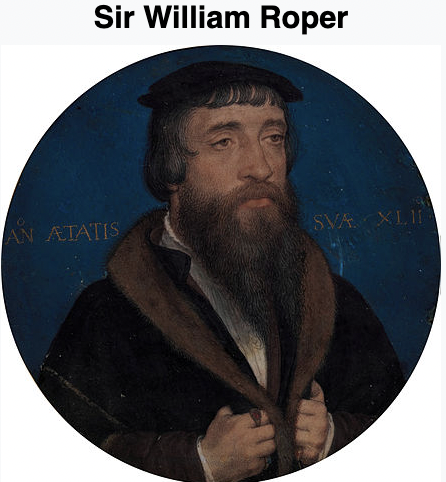

Lived in More Household for 16 Years

Roper’s Life of More has particular authority as it was written by More’s son-in-law who lived in the More household for sixteen years. Roper says that during those sixteen years he could not recall More being in a fume, being ill-tempered.

Roper commenced living in the More household as a law student in, perhaps, 1518. Roper married More’s eldest daughter, Margaret (Meg), in 1521. Following their marriage, Roper and Margaret continued to live as part of the More household.

At some stage Roper became an ardent Lutheran, something of which his father-in-law disapproved. More prayed for Roper’s conversion, and, indeed, Roper did return to the practice of the faith, however, imperfect.

Roper had every opportunity to observe More, both during the 1520’s when More was on the ascendant, apparently Henry VIII’s close friend, one of Henry’s most trusted advisers, and during the 1530’s up to his death in 1535, when More seemed to be more and more in trouble as a result of his unwillingness to acknowledge Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church in England.

On Ascendant

In 1518, More entered the service of King Henry VIII, being appointed a Privy Councillor. Prior to entering the King’s service, More had worked as a commercial lawyer, on occasion, involved in international trade negotiations, as well as engaging in various administrative and political roles. This period before 1518 was a period when More was renowned, not only as a rising lawyer, but as a scholar of the Northern Renaissance, a reputation enhanced by the publication in 1516 of Utopia. After entering Henry VIII’s service in 1518, More continued his involvement in various international negotiations but on behalf of the English Crown.

In 1521, More was knighted. In 1523, More was appointed Speaker of House of Commons. In 1525, More was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, with administrative and judicial responsibility for much of northern England.

In 1526, More moved his household from London to Chelsea, a then rural setting, about ten miles outside London. More’s household was comfortable, and highly intellectual. More himself was fluent in Latin and Greek, as well as, of course, English. More insisted on the best available education for his daughters, as well as his son John. Visitors, representative of the Northern Renaissance, ensured Chelsea was no remote locale. More’s household included extended family, servants and others whose ‘culture’ was both learned and welcoming.

In 1526, Hans Holbein the Younger painted Thomas More and His Family at Chelsea. Later, Holbein would paint a portrait of More as Lord Chancellor.

In 1529, More was appointed Lord Chancellor of England, effectively Prime Minister. According to Cathy Curtis in George M Logan (ed) Cambridge Companion to Thomas More, More achieved much in public office, but frequently, through indirect and private counsel, unobtrusive but diligent diplomacy. Although More always presented a dutiful and discrete public persona in office, and in his surviving letters to Henry and Wolseley reveals little of his own opinions and judgment, More was quite capable of influencing opinion behind the scenes, or actively orchestrating opposition in Parliament, while being aware that, as Norfolk warned him, ‘the wrath of the king is death.’

More and Henry were great friends. When they had finished dealing with affairs of state, they chatted about astronomy, geometry, theology, and so on. Henry even visited More at Chelsea. Both Henry and Catherine of Aragon found More a convivial companion.

More repeatedly expressed his position privately to Henry VIII as regards the royal marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and as regards the headship of the Church. Henry agreed to respect More’s conscience.

In 1529 More published A Dialogue Concerning Heresies. This was a response to the explosion of Lutheran ideas on the Continent, and also in England. More was regarded by Henry VIII and the English bishops as a brilliant and effective defender of Catholic orthodoxy.

Henry VIII

Henry VIII had been awarded the title, Defender of the Faith, by the Pope for his writing on the Seven Sacraments. More advised Henry against enhancing the power of the papacy (at the time the papacy was a secular power), advice Henry rejected. Not only did Henry disdain the protestant position, he arguably regarded himself as a “Catholic” until he died. It is suggested, on his deathbed, Henry was reconciled to the Church, confessing his sins, as well as receiving the Last Rites including Viaticum. Henry VIII was a bad man and a bad Catholic, but arguably never ceased to be a “Catholic”, at least in his own mind.

Henry was repeatedly unfaithful. He murdered two of his six wives. Henry murdered his closest associates. As Professor Dale Hoak has commented:

The anger that sprang from self-pity could lead to extreme cruelty towards those Henry felt had betrayed him or his trust…He became at times a petulant bully – beheading, hanging, burning – anybody who crossed him, anybody who refused his wilful demands. The record of his destructiveness towards others runs like a spreading stain across his entire reign. The full list of those at the top includes the execution of two wives, a Cardinal of the Church – that’s Fisher, a Lord Chancellor – that’s More, a marquis, two earls, a countess, a viscount, a viscountess, four barons, hundreds of subjects, commoners who resisted his authority, for example at the time of the Pilgrimage of Grace.

Betrayal – Henry thought many, these people, all of them, had betrayed him. When you start looking at the nature of what Henry thought was betrayal, a different construction can be advanced. Betrayal in many cases simply meant otherwise loyal servants opposed his will, disagreed with him.

Henry, in the late 1530s, destroyed the monasteries of England to finance his wars abroad, failing to replace the contribution monasteries made to agricultural innovation, public health, education, prevention and relief of poverty.

In 1531 Henry VIII, fuelled by the papal refusal to nullify his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, invented a new title for himself: Supreme Head of the Church of England. The English bishops, in breach of their duty as successors of the Apostles, agreed to this “so far as the law of Christ allows”. Henry’s legacy was only too predictable-religious conflict, dynastic instability and civil war in the 17th century.

More in Trouble

In 1532 More resigned as Lord Chancellor. The event which preceded More’s resignation was the Submission of Clergy, the acceptance by the bishops of Henry VIII’s authority over the Church of England. More’s previous very substantial income stopped, following his resignation as Chancellor.

In 1533 Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn. That year Cranmer was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury. Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon was declared invalid by Parliament, and his marriage to Anne Boleyn was recognised as legal. Subsequently, Anne Boleyn was crowned Queen. More refused to attend the coronation.

In 1534 More was questioned by Cromwell regarding his attitude to Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn. More was offered reinstatement to honour and wealth in exchange for his approval of the divorce. More refused. Later that year More refused to swear an oath acknowledging Henry as Supreme Head of the Church of England.

In 1534 More was imprisoned in the Tower of London. During his imprisonment, More wrote the Treatise on the Passion, A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation, A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body of Our Lord and The Sadness of Christ, spiritual classics which best express his mind (the so called Tower works).

The Essential Works

Published in 2020 by Yale University Press is Gerard Wegemer and Stephen Smith The Essential Works of Thomas More, comprising More’s most important writing in one thick volume, far more accessible than the scholarly Yale Collected Works in fifteen volumes. The Yale Collected Works is for scholars, the Essential Works for those whose only time for reading is snatched from all sorts of unscholarly activity, after a busy day, before sleep.

The Essential Works makes Thomas More, in all his complexity, readily available. In somewhat under 1,500 pages, laced with succinct but insightful introductions, and well-targeted footnotes, accompanied by a manageable chronology which recounts More’s life, we have all of More’s significant writings in English in one place:

- More’s English poetry;

- The Life of John Pico (1510);

- The History of King Richard III (1513 but unpublished in More’s lifetime);

- Utopia (1516);

- More’s Epigrams;

- More’s Letters (1501-1534, 1534-1535);

- A Dialogue Against Heresies (1529);

- The Supplication of Souls (1529)

- The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer (selections) (1532-1533);

- The Apology of Sir Thomas More, Knight (1533);

- The Debellation of Salem and Bizance (selections) (1533);

- The Answer to a Poisoned Book (1533, a defence of the Eucharist, the last book written by More and published in his lifetime);

- A Treatise Upon the Passion of Christ (1533, unfinished);

- A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body of Our Lord Sacramentally and Virtually (1534);

- A Dialogue of Against Tribulation (1534);

- The Sadness of Christ (1535, More’s final work);

- More’s Instructions, Meditations and Prayers.

Also included is a Reconstruction of More’s “trial”, together with the relevant legal texts, enabling one to form a legal assessment of More’s ‘trial’, days before his judicial murder. Included also are the earliest biographical accounts of More, including Erasmus, William Tyndale, Reginald Pole, and William Roper.

Roughly 500 years after William Rastell’s 1557 collection, The Works of Thomas More Knight, we now have in English, a second opportunity to read More’s Essential Works, showing his development from early adulthood to the time of his death in 1535. More speaks to us today!

The Essential Works will revolutionise contemporary understanding of More. This is the complete More, all in one location, accompanied by scholarly help for the non-specialist reader. Here, More speaks himself rather than through writers with particular axes to grind.

Trial and Death

Early in 1535 Cromwell offered More another opportunity to reconsider his position. More again refused. On 22 June 1535 More’s friend Bishop (newly appointed Cardinal) John Fisher, Bishop of London, erstwhile friend of both More and Henry, was executed. What was at stake, explained by Peter Marshall in the Cambridge Companion to Thomas More, is that More would not swear because the preamble to the oath upheld the spiritual validity of the King’s second marriage and implicitly rejected the authority of the Pope. For him to swear such an oath against his belief to the contrary, would have been perjury, not just a legal indiscretion. For More, ‘conscience’ was something persons had a duty to form in accordance with objective and accepted moral standards, principally the authoritative teaching of the universal Church.

The trial of Thomas More, according to Peter Marshall, was a foregone conclusion:

The commission trying More comprised a group of professional judges and reliable courtiers, including Cromwell, Lord Chancellor Audley, the dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, and Anne Boleyn’s father, the earl of Wilshire. Sir Christopher Hales, Attorney General, led the prosecution. The jury contained members who bore personal grudges against More. As was usual in treason trials, the accused was given no copy of the indictment, no right to call witnesses and no legal counsel, although it is hard to imagine where More might have found a finer legal mind than his own to conduct his defence.

More listened intently as a long indictment in Latin was read out…More now fought, brilliantly, for his life.

But the result was inevitable. On 1 July 1535 More was found guilty of treason, and sentenced to be hanged, cut down while still living, his bowels pulled from his body and burned in his sight, his genitals cut off, his head as well, and his body quartered, and put on view to the public. Shortly before execution, the sentence was commuted to beheading. More’s trial was a kangaroo court, with judges and jurors doing Henry’s bidding.

Kelly, Carlin, and Wegemer Thomas More’s Trial by Jury, though published as long ago as 2011, is an essential guide including:

- A procedural review of Thomas More’s trial.

- Natural law and the trial of Thomas More.

- A guide to Thomas More’s trial for modern lawyers.

- More’s three prison letters, commenting on his interrogation.

- A Judicial commentary on More’s trial.

- A docudrama on More’s trial based on primary legal materials.

Henry VIII and More

The masterful Preface summarises the different perspective between Henry VIII and More:

Henry VIII and Thomas More joined together at first to oppose Luther in what they perceived as heresies in his writings, but they were later come to a parting of minds. They differed less on doctrine and faith than on Church law and discipline, with More considering Henry not a heretic but rather a schismatic, an advocate of Caesaropapism, ‘the supremacy of the civil power in the control of ecclesiastical affairs.’

The measure of More is summarised in the following excerpts from More’s Trial Reconstructed:

Here indeed is a place of discord, dissension, and tumult, but I go now to where the root of all strife and dissension is removed, where love, peace, concord, and tranquillity will live in all.

But still I have great hope in the divine clemency and goodness that, as we read that St Paul persecuted Blessed Stephen, they are now together in heaven, so all of us, though we disagree in this life, will nevertheless agree in another life with perfect charity. I therefore pray the great good God to guard the King, conserve him, and make him safe, and send him salutary counsel.

I verily trust, and shall therefore right heartily pray, that though your lordships have now here on earth been judges to my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together, to our everlasting salvation.

On 6 July 1535 More was beheaded. More begged the crowd to pray for him and for the King, declaring he died “the King’s good servant but God’s first”. Kneeling down More prayed the Miserere (Psalm 51, “Have mercy on me, O God”), and kissed his executioner in an act of forgiveness.

The Life of Sir Thomas More

Although written in the mid sixteenth century, well after More’s death, Roper’s The Life of Sir Thomas Morewas not published until 1626, and then in France. Roper’s Life precedes the judgment of the Church, More only being beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886, and canonised by Pope Pius XI in 1935. In 2000 Pope St John Paul II declared More the Patron of Statesmen and Politicians.

Roper’s Life has the merit of being a little over 20 pages in the Essential Works, so it can easily be read in a single session. Roper’s Life has been criticised, especially by the “revisionists” who have challenged More’s reputation in recent years. Yet, to my mind, the revisionists have not established a credible case against Roper’s account of More. Quite the contrary, as an intimate within the More household, Roper was in a unique position to know the “real” More. Roper focuses on More the person in his day-to-day dealings. Hence Roper brings a unique perspective to his subject, a perspective of which no other Morean specialist is capable.

I highlight a few passages from Roper’s Life:

Justice

“Howbeit this one thing, son, I assure the, on my faith, that if the parties will at my hands call for justice, then all were it my father stood on the one side, and the devil on the other, his cause being good, the devil should have right.”

Advice

“Master Cromwell, you are now entered into the service of the most noble, wise, and liberal prince. You will follow my poor advice you shall, in your counsel-giving unto his grace, ever tell him what he ought to do but never what he is able to do. So shall you show yourself a true faithful servant and a right-worthy counsellor. For if a lion knew his own strength, hard were it for any man to rule him

Suffering

“We may not look at our pleasure to go to heaven in featherbeds. It is not the way, for our Lord himself went thither with great pain and by many tribulations, which was the path wherein he walked thither. For the servant may not look to be in better ease than his master.”

Standing Fast

“It is no mastery for you children to go to heaven, for everybody giveth you good counsel, everybody giveth you good example – you see virtue rewarded and vice punished. So, that you are carried up to heaven by the chins. But if you live in the time that no man will give you good counsel, nor man will give you good example, when you shall see virtue punished, and vice rewarded, if you will then stand fast and firmly stick to God, upon pain of my life, though you be but half good, God will allow you for whole good.”

Roper

Roper did not die until 1578 at the age of 83. Roper’s spouse, Margaret More, died many years earlier in 1544. It is perhaps a mark of Roper’s devotion to Margaret that he never remarried. Roper engaged in litigation about property against More’s widow Dame Alice. Roper also engaged in litigation in respect of his father’s will. Was Roper a difficult character? Perhaps. Roper made sufficient “compromises” to continue living and working as a lawyer in England. Although a Catholic until his death, Roper, along with the rest of the More family, took the oath, acknowledging Henry VIII as Supreme Head of the Church of England. So, Roper is a complex character.

This only enhances the credibility of Roper’s account of his father-in-law. Roper was in a position to know where the bodies were buried as regards More’s personal and family life. There weren’t any.

Reading Roper’s Life, and Wegemer and Smith Essential Works (together with other works of genuine scholarship), is the best way to understand Sir Thomas More, indeed, St Thomas More. In particular, the Tower works (A Treatise upon the Passion of Christ, A Treatise to Receive the Blessed, Body of Our Lord, A Dialogue Against Tribulation, The Sadness of Christ) demonstrate the mind of a saint. Another way perhaps of considering this is that More, like all of us, changed over time. But not all of us change for the better! By the time of his death, More was possessed by love of God, and love of all those with whom he came into contact. That involved the struggle of a lifetime.

Michael McAuley

Feast of St Thomas More 2022

Thomas More’s World

| Date | Event |

| 1478 | More born. |

| 1484 – 1503 | Pope Alexander VI used bribes to secure his election, moved into Vatican with wife and 7 children, and had a child with daughter, Lucretia, put the Borgia family in charge of papal states. Alexander IV was accused of poisoning many opponents, and he himself died this way. |

| 1482 – 1490 | More at St Anthony’s School, Threadneedle Street, London. |

| 1485 | Invasion of England by Henry Tudor. Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at Battle of Bosworth Field. |

| 1485 – 1603 | Tudor dynasty in England. |

| 1485 – 1509 | King Henry VII. |

| 1482 – 1490 | Bartolomeu Dias rounds Cape of Good Hope opening sea route to India. |

| 1482 – 1490 | More page for Archbishop and Lord Chancellor Morton. |

| 1492 | Spanish Christians complete Reconquista. Christopher Columbus embarks on Atlantic crossing, discovering America. Expulsion of Jews from Spain. |

| 1492 | More studies at Oxford. |

| 1493 | Christopher Columbus’ second voyage, establishing permanent settlement in Caribbean. |

| 1494 | More at New Inn. |

| 1495 – 1498 | Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. |

| 1496 | More at Lincolns Inn. |

| 1497 | Portuguese explorer, Vasco De Gama, takes first Portuguese fleet to India. |

| 1499 | Michelangelo’s Pieta. |

| 1501 | Spanish traders commence taking slaves from Africa to Hispaniola. |

| 1501 | Prince Arthur marries Catherine of Aragon. |

| 1501 – 15 04 | More with Carthusians. |

| 1502 | Prince Arthur dies. |

| 1503 – 1513 | Pope Julius II, warrior Pope. |

| Early Professional Life | |

| 1504 | Michelangelo’s David completed. |

| 1504 | More in Parliament representing London. |

| 1505 | More marries Joanna Colt. More’s daughter, Margaret, was born. |

| 1506 – 1616 | Construction of current St Peter’s Basilica, Rome. |

| 1506 | More’s daughter, Elizabeth, is born. |

| 1507 | More’s daughter, Cecily, is born. |

| 1509 | More’s son, John, is born. |

| 1509 | Henry VIII marries Catherine of Aragon. |

| 1509 | King Henry VIII crowned following death of father, Henry VII. |

| 1509 | Desiderius Erasmus writes In Praise of Folly. |

| 1510 – 1518 | More Under Sheriff of London. |

| 1510 | Portuguese found trading colony at Goa, India. |

| 1511 | More’s wife, Joanna, dies. Marries Alice Middleton. |

| 1512 | England declares war on France. |

| 1513 | Prince Henry is born to Henry VIII and Catherine but dies the same day. |

| 1513 – 1521 | Pope Leo X (libertine). |

| 1513 | Vasco de Balboa crossed Central America and discovered the Pacific. |

| 1514 | Portuguese arrive in Macao. |

| 1514 | More Commissioner of Sewers. |

| 1515 | More on trade delegation to Flanders. |

| 1515 | Prince Arthur is born to Henry VIII and Catherine but dies the same day. |

| 1516 | Erasmus produces printed edition of Greek New Testament. |

| 1516 | More publishes Utopia. |

| 1517 | Pope Leo X’s imposed 5 year truce on war between England and France, and called for united action against the Turks. |

| 1517 | Luther’s 95 theses at Wittenberg, the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. |

| More in King’s Service | |

| 1518 More joins Privy Council | |

| 1519 | Cortez lands in Vera Cruz, Mexico. |

| 1519 – 1522 | Cortez conquers Aztec of Mexico. |

| 1519 – 1522 | Magellan’s Voyage Around The World. |

| 1520 | More in Henry VIII’s entourage at Field of Cloth of Gold meeting with French King Francis I; takes place in trade negotiations with representatives of Hanseatic League at Bruges. |

| 1521 | More’s daughter, Margaret, marries Roper. |

| 1521 | Belgrade falls to Turks. |

| 1521 | More knighted, Under-Treasurer of Exchequer, assists Henry VIII with Henry’s anti-Lutheran treatise Defence of the Seven Sacraments. |

| 1522 | Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, converted from worldly life. |

| 1522 – 1534 | Luther’s German translation of Bible. |

| 1522 – 1523 | Pope Adrian VI begins reform in Catholic Church. |

| 1522 | Turks under Sulieman capture Rhodes. |

| 1523 – 1534 | Pope Clement VII. |

| 1523 | More Speaker of House of Commons. |

| 1523 | Capture of Rhodes from Hospitallers by Turks. The Hospitallers subsequently retreat to Malta. |

| 1524 | More moves to Chelsea. |

| 1525 | William Tyndale’s English translation of New Testament. |

| 1525 | Peasant revolt in southern Germany, condemned by Luther and ruthlessly put down by nobility. |

| 1525 | More is appointed Chancellor of Duchy of Lancaster. |

| 1526 | Hungary falls to Turks at Battle of Mohacz. |

| 1527 | Rome sacked by Lutheran troops of Catholic Emperor Charles who is seeking to expand Holy Roman Empire in Italy. |

| 1527 | More first consulted by Henry VIII about possibility of divorcing Catherine of Aragon. |

| 1528 | Santes Pagnino divided chapters of Bible into verses. |

| 1528 | William Tyndale’s Obedience of the Christian Man (the first work of divine right theory in English) which Anne Boleyn gives to Henry VIII. |

| 1529 | Ottoman Turks at gates of Vienna but subsequently driven back by Charles V with help of Lutheran forces. |

| 1529 | More appointed Lord Chancellor. |

| 1529 – 1555 | Civil War between protestant princes and Catholic Emperor in what is now Germany. |

| 1531 | Pizzaro commences conquest of Inca Empire in Northern Peru. |

| 1531 | Apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe to St Juan Diego. |

| 1532 | More resigns as Lord Chancellor following Submission of Clergy in which bishops acknowledge Henry as Supreme Head of Church of England. |

| 1533 | Henry VIII secretly marries Anne Boleyn. |

| 1534 | Nicholas Copernicus On the Revolution of the Heavenly Bodies challenged Ptolemiac model that earth is centre of the universe, suggesting that sun was centre of the universe. |

| 1534 – 1549 | Pope Paul III, a reforming pope, called Council of Trent. |

| 17 April 1534 | More imprisoned. |

| 1 July 1535 | More tried and found guilty of treason. |

| 6 July 1535 | More executed. |

| 1886 | More beatified. |

| 1935 | More canonised. |

| 2000 | More declared Patron of Statesmen and Politicians |