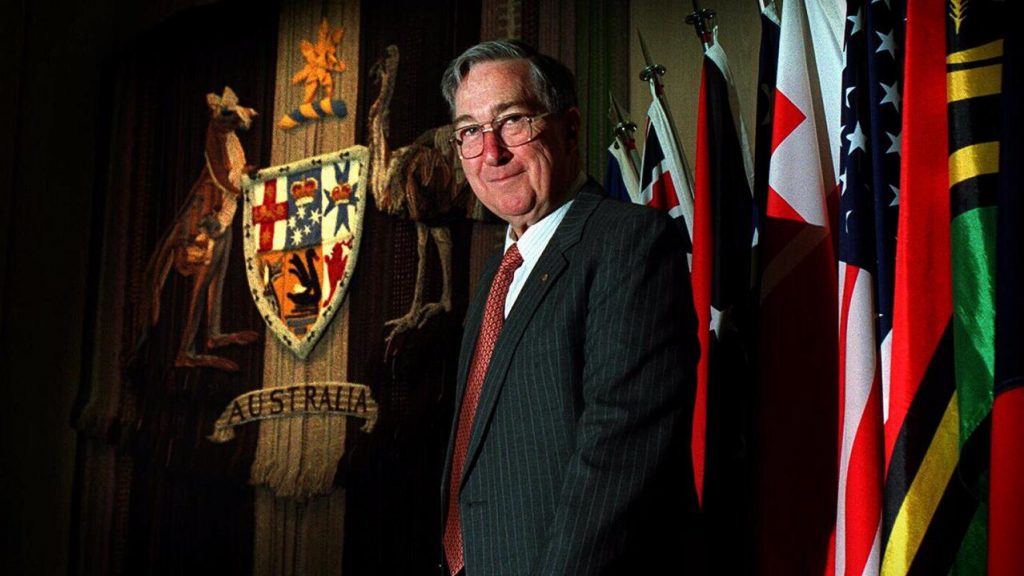

The death of Sir Gerard Brennan, on 1 June 2022, at the age of 94, brings to mind a lawyer who epitomises everything a good lawyer ought be.

Sir Gerard Brennan was born in Rockhampton, Queensland. He was the son of Frank Brennan, a Labor politician, and later a judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland. While at university, young Gerard Brennan was elected, in 1949, President of the National Union of Australian University Students (NUAS). Sir Gerard Brennan was admitted to the Bar in 1951.

In 1953 Sir Gerard Brennan married Dr Patricia O’Hara. Lady Brennan died on 3 September 2019. Sir Gerard and Lady Brennan have seven children – Frank, Madeline, Anne, Thomas, Margaret, Paul, and Bernadette.

Aboriginal Land

In 1973 Sir Gerard Brennan was briefed to represent the Northern Land Council before the Woodward Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights in the Northern Territory. The findings of the Royal Commission were the basis for the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, the first attempt by an Australian Government to recognise Aboriginal land ownership.

High Court

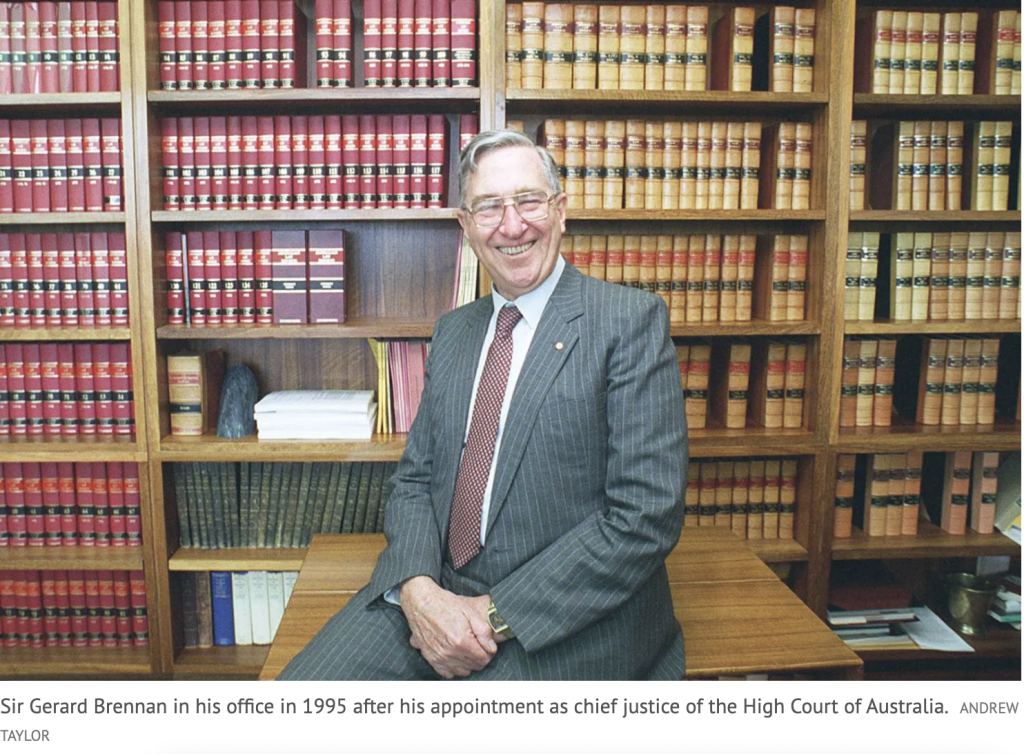

Sir Gerard Brennan was appointed to the High Court in 1981 by the then Fraser Government. In 1995, Sir Gerard Brennan was appointed the tenth Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia by the then Keating Government.

Mabo

In 1992 Sir Gerard Brennan wrote the leading judgment in Mabo v Queensland (No 2), putting an end to the legal doctrine of terra nullius, the fiction that at the time of European settlement, Australia was uninhabited. Brennan J (as he then was) commented in the course of the leading judgment:

The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country…Whatever the justification advanced in earlier days for refusing to recognize the rights and interests in land of the indigenous inhabitants of settled colonies, an unjust and discriminatory doctrine of that kind can no longer be accepted. The expectations of the international community accord in this respect with the contemporary values of the Australian people…The common law does not necessarily conform with international law, but international law is a legitimate and important influence on the development of the common law, especially when international law declares the existence of universal human rights. A common law doctrine founded on unjust discrimination in the enjoyment of civil and political rights demands reconsideration. It is contrary both to international standards and to the fundamental values of our common law to entrench a discriminatory rule which, because of the supposed position on the scale of social organization of the indigenous inhabitants of a settled colony, denies them a right to occupy their traditional lands.

Human Dignity

In the same volume of the Commonwealth Law Reports, Brennan J, in a dissenting decision, in Marion’s Case said:

Each person has a unique dignity which the law respects and which it will protect. Human dignityis a value common to our municipal law and to international instruments relating to human rights…Our law admits of no discrimination against the weak and disadvantaged in their human dignity.

Although Brennan J’s dictum is part of a dissenting judgment, it expresses a principle from which, surely there can be no dissent, a principle which is fundamental to Australian law, indeed, to any law which is worthy of the name.

Speaking for Himself

While there have been, and no doubt will be, many comments on the life of Sir Gerard Brennan, and on the Brennan High Court, perhaps, Sir Gerard can be allowed to speak for himself. Sir Gerard’s comments at his swearing in as Chief Justice on 21 April 1995 sum up this extraordinary judge, this extraordinary person:

I am grateful for the excessive generosity in the remarks you have made this morning. It comforts me to think that I must have learned to conceal most shortcomings in the fifty years since I first entered my father’s Court to arraign a prisoner at the commencement of the criminal trial. Picking up the indictment and misreading the name of the prosecutor for the name of the accused, I charged one of the dearest and most up-right men with the crime of rape. Such is the camaraderie of the Bar, that counsel for the accused leapt to his feet and pleaded not guilty on behalf of his learned friend….

Today’s ceremonies are not empty rituals. This Court’s practice is to administer the Oath of Allegiance and Office in public. That is not a matter of formal procedure. It is a public witnessing of the making of two solemn promises for the performance of which the oath taker will be responsible not only to this Court and this country but also to his Creator. Statute requires that the Oath or a like affirmation be taken before a Chief Justice or Justice enters upon the duties of his or her office.

The first promise is a commitment of loyalty to Her Majesty the Queen her heirs and successors according to law. It is a commitment to the head of State under the Constitution. It is from the Constitution that the Oath of Allegiance, which has its origins in feudal England, takes it significance in the present day. As the Constitution can now be abrogated or amended only by the Australian people in whom, therefore, the ultimate sovereignty of the nation resides, the Oath of Allegiance and the undertaking to serve the head of State as Chief Justice are a promise of fidelity and service to the Australian people. The duties which the oath imposes sit lightly on a citizen of the nation which the Constitution summoned into being and which it sustains. Allegiance to a young, free and confident nation governed by the rule of law is not a burden but a privilege.

The second promise is to “do right to all manner of people according to law without fear or favour, affection or ill-will“. The form can be traced back to a statute of Edward III, but its substance is of enduring relevance. In substantially that form, the oath or affirmation is taken by every judge. It is rich in meaning. It precludes partisanship for a cause, however worthy to the eyes of a protagonist that cause may be. It forbids any judge to regard himself or herself as a representative of a section of society. It forbids partiality and, most importantly, it commands independence from any influence that might improperly tilt the scales of justice. When the case is heard, the judge must decide it in the lonely room of his or her own conscience but in accordance with the law. That is the way in which right is done without fear or favour, affection or ill-will. Judges sometimes appear to be remote, belonging to what have been described as “the chill and distant heights”. In the doing of justice that must be so. Justice is not done in public rallies. Nor can it be done by opinion polls or in the comment or correspondence columns of the journals.

The oath requires justice to be done according to law. The content of the duty thus accepted depends upon the jurisdiction to be exercised. In the trial courts of this country, the rules of law prevail. And so they must, for it would do no justice to give judgment according to an abstract notion of what is right in the knowledge that the judgment would be overruled on appeal. In appellate courts, the law may authorize a tension between abstract justice and a rule of law to be resolved by an alteration of the rule. In either case, the jurisdiction of the court is fixed by law and judgment must be rendered in accordance with the judicial method. The security which each of us has is the law. Sir Thomas More of the Man for All Seasons is surely right to put to Roper –

“This country’s planted thick with laws from coast to coast… and if you cut them down…d’you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then?”

Insistence on the rule of law has a corollary which is implicit in the terms of the judicial oath. If right is to be done according to law, right will be done only if the law be just. Such tension as there is between justice and the rules of law surfaces most acutely in litigation before the High Court, partly because of history, partly because of procedure. With the abolition of the last appeals from Australian Courts to the Privy Council, this Court was charged with the ultimate responsibility of declaring the law for this country. This did not mean that we were free to cast aside the priceless heritage of the common law of England, but it did mean that this Court had to examine critically those rules of the common lawincluding the rules of statutory interpretation in the light of our own history, culture and social conditions. Long-standing rules of tort and contract, of land law, equity and administrative law have been revisited in recent years. The same factors and the ever-changing problems of government have evoked renewed examination of the spare text of our Constitution.

Then, with the increasing volume of appeals to this Court, it became necessary to introduce the procedural filter of a grant of special leave to appeal. The result is that a considerable proportion of the cases to be decided by this Court involve rules of law that have already proved to be questionable, or at least productive of uncertainty in the Courts below. In cases in both its original and appellate jurisdictions, the Court has had to grapple with issues on which two or more views can reasonably be held. Decisions have not always been reached by more than a narrow majority, but that is not to be wondered at. Where the review of existing rules is in question, the judicial oath to do right according to law sometimes places emphasis on abstract justice, sometimes on the existing rule. And when constitutional doctrine is to be re-examined, the frustration of powerful interests frequently follows. It is inevitable in these circumstances that the decisions of this Court would be seen by many to have a legislative flavour.

But this Court is not a Parliament of policy; it is a court of law. Judicial method is not concerned with the ephemeral opinions of the community. The law is most needed when it stands against popular attitudes sometimes engendered by those with power and when it protects the unpopular against the clamour of the multitude. But judicial method is concerned with the equal dignity of every person, his or her capacity to participate in the life of the community, to contribute to society and to share in its benefits; it is concerned with the powers entrusted to Governments and the manner in which those powers are exercised. Judicial method starts with an understanding of the existing rules; it seeks to perceive the principle that underlies them and, at an even deeper level, the values that underlie the principle. At the appellate level, analogy and experience, as well as logic, have a part to play. Judgments must be principled, reasoned and objective, as Sir Anthony Mason said yesterday. And, most significantly, each step in the reasoning must be exposed for public examination and criticism.

Herein lies a difficulty. The work of this Court is rightly a subject of considerable public interest. Though the arguments heard here are often at a high level of abstraction, the emerging principles have a concrete effect on the liberties, relationships and property of individual persons, both natural and artificial. Therefore the work of this Court should be subject to informed public scrutiny. But how is it possible for the public to be informed? It is unrealistic to expect the arid fields of law to be tilled in the popular press, much less in the brief and adversarial encounters of the television screen. Of course, there are some few highly competent legal journalists but an adequate analysis of legal principle and its significance may be precluded by limited space or may give way to a story of more gripping, if ephemeral, interest. The problem of fostering informed public appreciation of the laws by which we are governed and protected is, I venture to suggest, a problem far from satisfactory solution. It will not be resolved by superficial comment or by an expression of pleasure or disappointment in advancing policy or interest.

Nevertheless, the public interest in the judgments of this and other Courts is a clear and gratifying indication that, in this country, we are governed by the rule of law. The Courts have earned and maintained public confidence in their unfailing response to every reasonable application, to their impartiality and the fearless administration of the law. Today’s focus is on the work of the High Court, but it must be remembered that the face of justice is more often the face of the magistrate and the judge at trial.

St Thomas More

Sir Gerard Brennan had prominently displayed in his Chambers a reproduction of the Holbein portrait of St Thomas More.

Judicial Method

Belinda Baker and Stephen Gageler (the latter, prior to his appointment as a Justice of the High Court), contributed to the Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia an entry on Sir Gerard Brennan, commenting that for Sir Gerard Brennan, judicial method began with a thorough understanding of the existing case law. According to Baker and Gageler, Brennan’s judgments uniformly displayed great industry and attention to history. From the existing case law, Brennan sought to discern underlying values and principles. Those values and principles were weighed against the enduring values and principles of the Australian legal system as a whole. They were then applied to refine and, where necessary, reformulate the specific legal rules. According to Baker and Gageler, Sir Gerard Brennan saw that the courts could, in this way, legitimately develop the law to keep pace with contemporary social and economic conditions. However, for Sir Gerard Brennan the courts had no role in rejecting and replacing legal rules in the pursuit of social or economic ends. Nor could they bring about a change in the law simply to achieve tidiness or conceptual purity. Overruling, according to Baker and Gageler, was properly confined to those rare cases where specific legal rules proved to have been unworkable, or where to continue to apply them, would perpetuate injustice.

Locking Up Children

In June 2021, long after he had retired as a judge, Sir Gerard Brennan commented on a public debate over a family of asylum seekers, supporting the family with a letter in the Sydney Morning Herald:

Are other Australians ashamed, as I am? How can Australia, proud of our freedoms, respectful of all our people, and insistent on human dignity, inflict cruelty on Australian children, as a means of achieving a goal of government policy?

Inclusiveness and Respect for Human Rights

After Sir Gerard Brennan’s retirement from the High Court, Sir Gerard commented, in an address to principals of Catholic Schools, inclusiveness is the state of mind of a Christian who wants to live out the New Commandment – to love one another, as I have loved you. The Christian does not discriminate amongst people of different races or of different social classes or different cultures. All of us are children of God, with the divine spark and eternal destiny. Our common humanity imports a mutual concern for and interest in all people. According to Sir Gerard Brennan, inclusiveness and respect for the human rights of all people are not optional for a Christian. They are at the heart of Christian belief and practice.

Not all of us can be judges, not all of us can be Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, but we can all, in our practice of law, emulate the virtues of Sir Gerard Brennan, and serve others in the course of our practice, doing justice according to law, in our particular role as lawyers. The life of Sir Gerard Brennan was one of an unpretentious, but accomplished lawyer, a great person.

Michael McAuley

9 June 2022