Tolkien’s (pronounced “Tolkeen”) three volume fantasy epic, The Lord of the Rings, was published in 1954-55. Peter Jackson’s three-part film version was released in 2003-2004. While there are mixed views amongst the critics, my older grandchildren enjoyed watching Peter Jackson’s film version. Watching Peter Jackson’s film version has led my older grandchildren to read The Lord of the Rings. Jeff Bezos’ Amazon series, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, debuting on 2 September 2022, on Prime TV, is apparently drawn from the ‘backstory’ to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, based on works published only after Tolkien’s death. My grandchildren cannot wait! This will likely be the most expensive, most elaborate TV series ever made.

The Ring

The Lord of the Rings is the evil genius Sauron. His influence is everywhere. Sauron’s depersonalising quest for power causes Sauron to seek to recover the Ring originally in his possession. The Ring, while prolonging life, makes one disappear. Whilst Saroun’s influence is everywhere, there is no precise physical description of him. The lack of physical definition is consistent with Tolkien’s understanding of evil as the lack of due good. For Tolkien, nature, the body, and bodily realities, are good.

Ring of Gyges

There are shades here of Plato in the Republic and the Ring of Gyges. There is an association between Sauron, technology and dehumanising work, for instance in the mines of Mordor. The agents of Sauron cut down trees. Cutting down of trees is evil. By contrast the world of nature is good.

Power

Sauron seeks to recover the Ring in his quest for power. Recalled here is the Gospel account of the temptations of Christ:

“Again, the devil took him to a very high mountain, and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and the glory of them; and he said to him, ‘All these I will give you, if you will fall down, and worship me.'”

So, as I read Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings is about Sauron’s quest for power, associated with the destruction of nature, the idolisation of technology, and the destruction of the person. Gollum, the Ringwraiths, the Orcs, and Worm-tongue, are all diminished as persons. They lack due good. What happens to a person taken over by desire for the Ring (“my precious”) is demonstrated by the hobbit, Gollum, who has the Ring in his possession for 500 years. Gollum almost ceases to be recognisable as a hobbit. Gollum has lost his due good as a hobbit. The role of Frodo, the Ringbearer, is to bear the Ring to its destruction, but not to be seduced by the Ring with its depersonalising consequences. Frodo and Sam are, despite themselves, unlikely heroes. Frodo bears the Ring assisted by Sam Gangee, Merry and Pippin the faithful hobbits, Gandalf the wizard, Legolas the elf, Gimli the dwarf, Aragorn and Boromir men. The Fellowship of the Ring is broken by Boromir who, nevertheless, repents and recovers himself.

Summer Reading

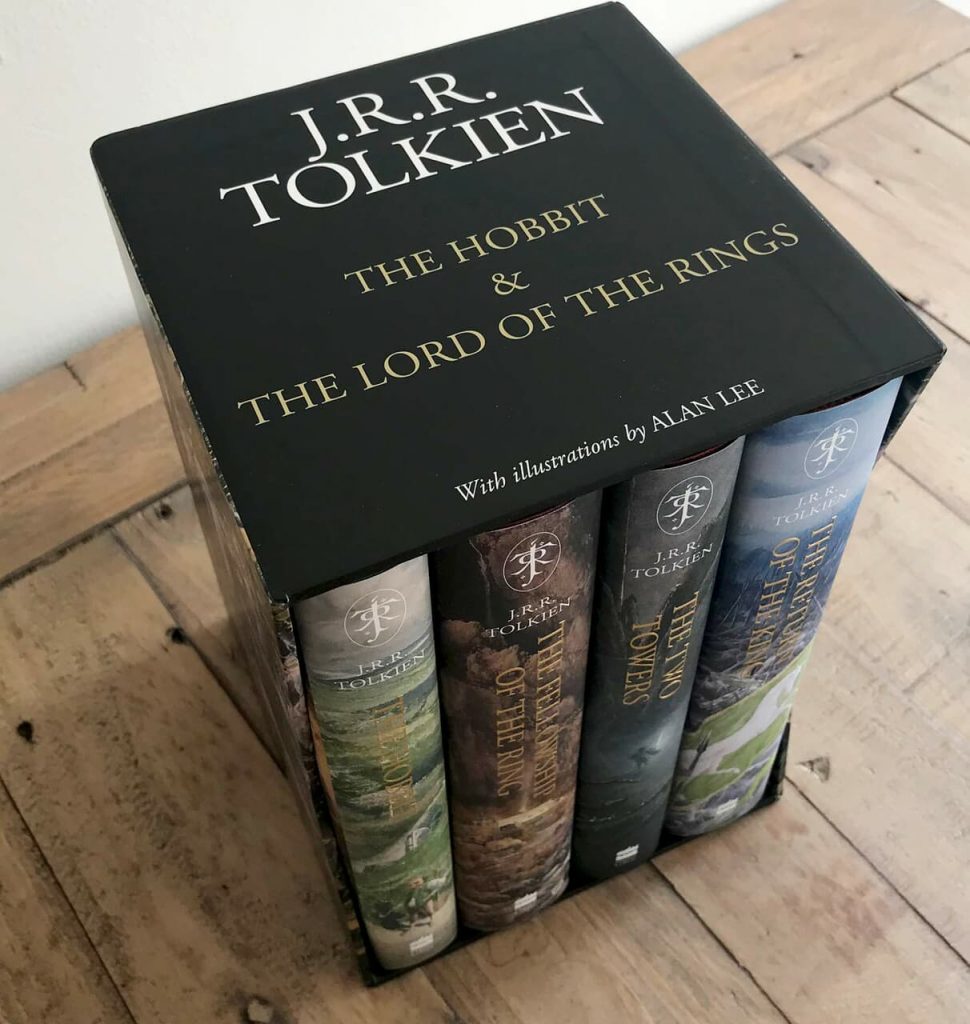

Over Summer I reread both Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. I had the experience of seeing, on a second reading, so much that I missed at the first reading, many years previous. I also reread Tolkien’s fairy stories including Farmer Giles Ham (1949), Smith of Wootton Major (1967), The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1961), Leaf by Niggle (1964), Roverandon (1968). I read Tolkien’s Father Christmas Letters, written and illustrated by Tolkien for Tolkien’s children each Christmas between 1924 and 1943, and only published in 1976, after Tolkien’s death. I read Mr Bliss written in 1936 for Tolkien’s children, eventually published after Tolkien’s death in 1973. Mr Bliss is a self-criticism of Tolkien’s absent-minded driving. Mr Bliss is beautifully illustrated by Tolkien, who was a fair artist. Finally, I planned to read Tolkien’s translation of, and introduction to the Old English classic Beowulf (1926) – but time ran out. Otherwise, I decided to largely, but not entirely, leave Tolkien’s posthumously published work for another time.

The Hobbit

The Hobbit was published in 1937. Tolkien had written The Hobbit for his four children – John, Michael, Christopher and Priscilla – not for publication. It was happenstance that The Hobbitcame to the publisher’s attention, and Tolkien was convinced to permit publication. The publication of The Hobbit was so successful the publisher wished to release a sequel. Hence, The Lord of the Rings – which is far from simply a children’s work, although read usefully by many children and teenagers.

Not Allegory

In Tolkien’s Introduction to The Lord of the Rings Tolkien denies he was writing “allegory”. Tolkien may not write “allegory”, but his writing is replete with allusion, much of which will be missed by those not familiar with life in the English West Midlands at the beginning of the 20th century; by those not familiar with Greek, Roman, Norse, Icelandic, Celtic, Finnish, Germanic language and mythology; nor familiar with Anglo-Saxon (Old English) language and literature; nor with life in the trenches in the First World War, nor with what seemed, at the time, clashes between good and evil in the Second World War. Tolkien was an immensely learned person, with great knowledge of many different languages, literature and history. So, all sorts of allusions fall from his pen. Because of the volume of his writing, one could spend a lifetime chasing down the origin of names, the allusions and the depths of what Tolkien has written.

Philologist

To fully appreciate Tolkien’s invention of names of persons, places, trees, plants, landscapes, weather patterns, one needs to be familiar with Greek, Latin, Norse, Icelandic, Anglo-Saxon, the various Germanic languages, Finnish, the Celtic languages, Old English, Middle English, Italian, French, and Spanish. To appreciate Tolkien, one ought keep in mind Tolkien was a professional philologist, studying language, familiar with many different languages, an inventor from the age of 13 or 14, not only of words, and sentences, but of whole languages.

Fantasy

Tolkien, in his lifetime, created a world of fantasy, what he called a ‘secondary world’, a world in which one can immerse oneself with a complete sense of reality, the world of Middle Earth, inventing languages, inventing a history of Middle Earth, which informed The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, such that these works could not be fully evaluated until after Tolkien’s death in the light of Tolkien’s voluminous posthumously published writings edited, by his son Christopher. The Silmarillion was published in 1977, following Tolkien’s death in 1973. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were drawn from The Silmarillion.

Darned Good Stories

It seems to me the best way to initially read Tolkien’s two masterpieces, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, is as darned good stories. To appreciate The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings it is not necessary to chase down the origin of every name and every allusion, to chase down every idea. It is sufficient to enjoy the story. Nevertheless, to fully understand The Hobbit, I recommend Joseph Pearce’s Bilbo’s Journey. Also, for The Lord of the Rings, Joseph Pearce’s Frodo’s Journey.

Tolkien a Hobbit

Tolkien regarded himself as a hobbit:

I am a hobbit (in all but size). I like gardens, trees, and unmechanised farmlands; I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking; I like and even dare to wear in these dull days, ornamental waistcoats. I am fond of mushrooms (out of the field); I have a very simple sense of humour (which even my appreciative critics find tiresome); I go to bed late and get up late (when possible). I do not travel much.

Bilbo and Frodo as Heroes

Amidst my summer reading, I listened to Tom Shippey’s Great Course Heroes and Legends: The Most Influential Characters of Literature, the opening episode of which is concerned with Bilbo Baggins (The Hobbit) and Frodo Baggins (The Lord of the Rings) as “heroes”. Shippey argues that hobbits, in particular, Bilbo of The Hobbit, and Frodo of The Lord of the Rings, are small, decidedly unwarlike creatures without strength or courage. Shippey asks-how can Bilbo and Frodo be heroes? The remainder of Shippey’s course is really a postscript to the lecture on Bilbo (The Hobbit) and Frodo (The Lord of the Rings), presenting a whole series of different and contrasting heroes-Homer’s Odysseus; Virgil’s Aeneas; Beowulf’s The god Thor; Robin Hood; Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote; Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe; Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet; Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes; Rudyard Kipling’s Mowgli the wolf child; George Orwell’s Winston Smith; Ian Fleming’s James Bond; and J K Rowling’s Harry Potter. The contrast enables Shippey to identify and highlight what is particular about the heroism of Bilbo, and his adoptive nephew Frodo.

Life

It helps to know something about Tolkien’s life, and so I read Humphrey Carpenter’s biography, JRR Tolkien, a work on which I draw extensively. Tolkien was born on 3 January 1892 in the then British colony of South Africa where his father, Arthur Tolkien, worked as a bank manager. Tolkien’s name was John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. His friends called him Tolkien. He was also on occasion called Ronald. Reuel was a family name, part of his father’s name. Tolkien wrote under the name JRR Tolkien. In 1894 Tolkien’s younger brother, Hilary, was born. As a toddler in South Africa, Tolkien was bitten by a tarantula, an incident some claim is significant for his description of the spider, Shelob, in volume 2 of The Lord of the Rings-a claim Tolkien denies.

West Midlands

In 1895 Tolkien’s mother, Mabel, and the boys returned from South Africa for a visit to England. As a result of Arthur Tolkien’s death in 1896, Mabel and the boys remained in England, living for a time in the West Midlands. The people of the West Midlands at the beginning of the 20th century are the inspiration for Tolkien’s depiction of hobbits.

Trees

Tolkien’s writings demonstrate a love of nature, especially trees. Tolkien deplored the destruction of the English countryside. While Tolkien did own a car for a period while his children were growing up, his preferred way of moving about was walking or riding a bicycle. Eventually Tolkien sold his car, and returned solely to walking and cycling. Tolkien deplored the destructive impact of industrialisation, and of the motor car on the English countryside, preferring older ways of doing things, often involving craftsmanship, to modern technology. It was typical of Tolkien that he never owned a television, something I wish could be said of me.

Mother

In 1900, Tolkien’s mother, Mabel, and the boys were received into the Catholic Church. The hostility of Mabel’s family was immediate and vigorous, depriving Mabel and the boys of much-needed support, both financial and other.

Tolkien’s education was initially at home where his accomplished mother, Mabel, introduced him to Latin, French and German, botany, music and art – and later at King Edwards School Birmingham where his aptitude for language was promoted, for instance, reading Chaucer in the original Middle English, as well as learning both Greek and Latin. From his earliest years Tolkien showed evidence of genius, particularly as regards linguistics and literature.

Orphan

In 1904 Mabel died of diabetes 1 (this was before the advent of insulin injections), leaving her two sons orphans. Tolkien was 12 years of age. Tolkien’s brother Hilary was 10. Before her death Mabel had arranged that Ronald and Hilary would be cared for by the Birmingham Oratory. Fr Francis Morgan, a priest (of Anglo-Spanish/Welsh origin) of the Oratory, became the boys’ guardian, effectively a father to Ronald and Hilary, providing financially for the boys, paying the fees at King Edwards School Birmingham. Ronald and Hilary lived in various boarding houses near the Birmingham Oratory.

Each day they served Mass for Fr Morgan, having breakfast with him after Mass, discussing the day’s affairs, playing with the monastery cat, which had taken up residence in the “drum” through which meals were served from the kitchen to the refectory. Fr Morgan used take Ronald and Hilary on holidays. Tolkien first came to know the Birmingham Oratory in about 1903, some years after the death in 1890 of its most famous member, Cardinal, now St, John Henry Newman. As Humphrey Carpenter has commented, after their mother Mabel’s death, the Oratory became the boys’ real home.

Edith Bratt

In 1908, Ronald, then aged 16, met Edith Bratt aged 19. Edith was also an orphan. Edith lived, for a time, in the same boarding house as the boys. In 1909 the brilliant young Tolkien, distracted by romance with Miss Bratt, unexpectedly failed his scholarship exam for Oxford. Fr Morgan moved Ronald and Hilary to other lodgings. Fr Morgan forbade any further communication with Miss Bratt-until Tolkien attained his majority at the age of 21. In 1911, Tolkien completed his education at King Edwards School. At King Edwards, Tolkien demonstrated a fascination with language, inventing languages, a practice which Tolkien continued with increasing sophistication all his life. By the end of his school years, Tolkien was developing a familiarity with Finnish and Norse mythology, as well as demonstrating an embryonic interest in Welsh. Tolkien loved Welsh names, first observing them on the side of trains near where he lived.

Languages

Tolkien’s writing of fantasy, both prose and poetry, was an accompaniment of his fascination with language, Tolkien giving particular attention to the creation of names of persons and places, as well as maps of the locales where the action of his fantasy writing took place. While at school Tolkien became familiar with the poetry of the English mystic Francis Thompson. Tolkien was a student at Oxford from 1911 to 1915, graduating with First Class Honours.

Marriage

Meanwhile, Tolkien turned 21 on 3 January 1913. Tolkien (who had obeyed Fr Morgan’s prohibition of communication) was, shortly after turning 21, reunited with Miss Bratt. Tolkien convinced Miss Bratt to break off an engagement to another young man. Edith and Tolkien were engaged in 1914. On 22 March 1916 Edith and Tolkien were married.

Army

In 1915 Tolkien joined the army as an officer. At the time of Edith and Tolkien’s marriage in 1916, there was every possibility of him being posted to the trench-war in France with not unlikely death or serious injury. Death in the trenches of France was the fate of most of Tolkien’s friends. Frodo’s companion, Sam Gamgee, in The Lord of the Rings, is drawn from soldiers Tolkien knew in the First World War, many from the English West Midlands.

Edith

Humphrey Carpenter comments on Tolkien’s relationship with Edith:

Those friends and others who knew Ronald and Edith Tolkien over the years never doubted that there was deep affection between them. It was visible both in small things, the almost absurd degree to which each worried about the other’s health, and the care with which they chose and wrapped each other’s birthday presents; and in large matters, the way in which Ronald willingly abandoned such a large part of his life in retirement to give Edith the last days at Bournemouth she felt she deserved, and the degree to which she showed pride in his fame as an author.

A principal source of happiness to them was their shared love for their family. This bound them together until the end of their lives, and it was perhaps the strongest force in their marriage. They delighted to discuss and mull over ever detail of the lives of their children, and later of their grandchildren…Tolkien was immensely kind and understanding as a father, never shy of kissing his sons in public, even when they were grown men, and never reserved in his display of warmth and love.

The Silmarillion

In 1917, while still in the Army, even while fighting in the trenches in the Somme, Tolkien began writing The Book of Lost Tales, which eventually became The Silmarillion. The Silmarillion was not published until 1977 after Tolkien’s death on 2 September 1973. The Silmarillion is essential for fully understanding Tolkien’s two major works published in his lifetime, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings. That Tolkien worked on The Silmarillion all his life – as well as other writing unpublished at the time of his death – illustrates the great care with which he approached composition, drafting and re-drafting, paying close attention to particular words, especially names of persons and places, close attention to phrases and sentences, reviewing his writing time and time again. Never did Tolkien write thoughtlessly.

God

Humphrey Carpenter comments on the place of God, the One, in The Silmarillion, and how the accounts contained therein are “true”:

Some have puzzled over the relation between Tolkien’s stories, and his Christianity and have found it difficult to understand how a devout Roman Catholic could write with such conviction about a world where God is not worshipped. But there is no mystery. The Silmarillion is the work of a profoundly religious man. It does not contradict Christianity but complements it. There is in the legend no worship of God, yet God is indeed there, more explicit in The Silmarillion than in the work that grew out of it, the Lord of the Rings. Tolkien’s universe is ruled over by God, ‘the One’. Beneath Him, in the hierarchy are ‘the Valar’, the guardians of the world who are not gods but angelic powers, themselves holy and subject to God; and at one terrible moment in the story, they surrender their power into His hands.

Tolkien casts his mythology in this form because he wanted it to be remote and strange, and yet, at the same time, not to be a lie. He wanted the mythological and legendary stories to express his own moral view of the universe; and as a Christian, he could not place this view in a cosmos without the God that he worshipped. At the same time, to set his stories ‘realistically’ in a known world, where religious beliefs were explicitly Christian, would deprive them of imaginative colour. So, while God is present in Tolkien’s universe, He remains unseen.

When he wrote The Silmarillion, Tolkien believed that in one sense he was writing the truth. He did not suppose that precisely such people as he described, ‘elves’, ‘dwarves’, and ‘malevolent orcs’, had worked the earth and done the deeds he had recorded. But he did feel, or hope, that his stories were, in some sense, an embodiment of profound truth. This is not to say that he was writing an allegory, far from it.

Niggle

Not without significance does Tolkien in his very self-critical autobiographical short story, Leaf by Niggle (published in 1944), refer to himself as Niggle. The artist, Niggle, never completes his depiction of a tree because he is so taken up with the depiction of a particular leaf.

With the end of the First World War, the “war to end all wars”, a slogan Tolkien never believed, Tolkien was discharged from the Army.

Academia

In 1918 Tolkien became an editor of the New Oxford Dictionary, concentrating on words commencing with the letter “W”. In 1920 Tolkien was appointed a Reader in English Literature at Leeds University. In 1924 Tolkien was appointed Professor of English Language at Leeds. In 1925 Tolkien published a collaborative academic work, Sir Garwain and the Green Knight. In 1925 Tolkien was appointed Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University. Tolkien’s focus was on the language, literature and history of Old English from the 5th to the 12th centuries. This period, largely the early Middle Ages, was a “heroic” period of English literature, much as the time of Homer, author of The Iliad, and The Odyssey, provided a heroic perspective for the Greeks. Tolkien and Edith lived in Oxford for forty-three years, rarely travelling beyond. While constantly travelling in his mind, physically Tolkien stayed put.

Lecturer

Despite varying accounts, Tolkien’s ability as a lecturer is described by Humphrey Carpenter:

But he invariably brought the subject alive and showed that it mattered to him. The most celebrated example of this, remembered by everyone who was taught by him, was the opening to his series of lectures on ‘Beowulf.’ He would come silently into the room, fix the audience with his gaze, and suddenly begin to proclaim in a resounding voice the opening lines of the poem in the original Anglo-Saxon, commencing with a great cry of: “Hwoet!” (the first word of this and several other old English poems), which some undergraduates took to be ‘Quiet!’ It was not so much a recitation as a dramatic performance, an impersonation of an Anglo-Saxon bard in a mead hall, and it impressed generations of students because it brought home to them that Beowulf, was not just a set text to be read for the purposes of an examination, but a powerful piece of dramatic poetry…

One reason for Tolkien’s effectiveness as a teacher was that besides being a philologist, he was a writer and poet, a man who not only studied words, but used them for poetic means. He could find poetry in the sound of the words themselves, as he had done since childhood; but he also had a poet’s understanding of how language is used.

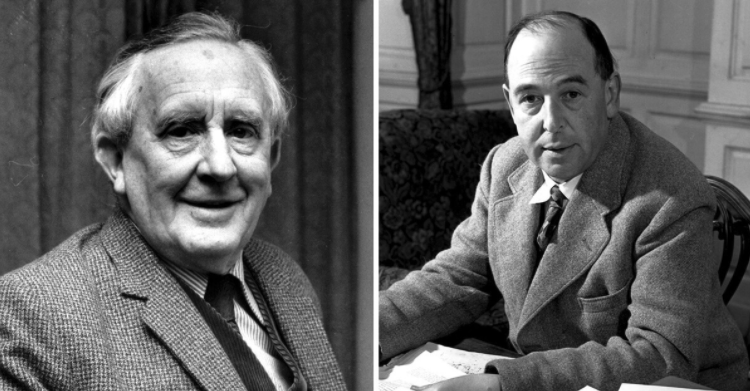

CS Lewis

In 1926 Tolkien met CS (Jack) Lewis with whom he developed a lifelong friendship. Although Tolkien was important in Lewis’ conversion to Christianity, he had little regard for the Anglican Church to which Lewis had returned. Tolkien and Lewis’ approaches to writing were very different. Tolkien rejected allegory in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings (but was capable of writing of it, as demonstrated in Leaf by Niggle). Tolkien was subtle and allusive. His writing reflected the person he was. CS Lewis wrote extensive allegory (for instance, his depiction of the Christ-like Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in the Narnia series). CS Lewis was very much the polemicist as demonstrated by his essays. Tolkien’s longstanding friendship with CS Lewis involved the Inklings, an informal group of Oxford intellectuals who met twice a week to read and discuss each others’ writings. To understand Tolkien and Lewis’ friendship, one might read the chapter on Friendship in Lewis’ The Four Loves.

Beowulf

In 1936 Tolkien’s translation of the Old English epic, Beowulf, together with a commentary, was published. This established Tolkien as the world expert on the greatest work of Old English literature. Tolkien’s interest in Beowulf posed the questions – Who is a hero? in what does heroism consist? These questions are central to both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

In 1945 Tolkien was appointed Merton Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford.

On Fairy Stories

That year 1945 Tolkien’s 1939 lecture On Fairy Stories at the University of St Andrews was published. It seems to me that this lecture is the key to understanding Tolkien’s writings:

Probably every writer making a secondary world, a fantasy, every sub-creator, wishes in some measure to be a real maker, or hopes that he is drawing on reality: hopes that the peculiar quality of the secondary world (if not all the details) are derived from Reality, or are flowing into it…the peculiar quality of the ‘joy’ in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as the sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth.

Farmer Giles of Ham

In 1949 Farmer Giles of Ham was published. Like so much of Tolkien’s writing, Farmer Gilesbegan as a story for Tolkien’s children. Like Tolkien’s more significant writing, Tolkien is concerned with: Who is a hero? What makes a hero?

In 1959 Tolkien retired from Oxford University, opening up more time to continue his writing of fantasy.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

In 1962 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil were published. Again, Tom Bombadil began as a response to family urging. Tom Bombadil displays Tolkien’s skill, not only as a writer, but as a poet. Tom Bombadil and his spouse, Goldberry, are prelapsarian figures, and hence need to be considered in the context of Tolkien’s world view.

Smith of Wootton Major

In 1967 Smith of Wootton Major was published. Smith of Wootton Major is a Fairie Story which cannot be fully understood except having read Tolkien’s 1939 lecture at the University of St Andrews On Fairie-Story.

In 1968, at the urging of Edith, Tolkien moved from his beloved Oxford to the sea-side town of Bournemouth where they lived until Edith’s death in 1971. After Edith’s death in 1971 Tolkien returned to Oxford.

Ordinary

Tolkien’s life is summed up by Humphrey Carpenter, from the time he married Edith Bratt on 23 March 1916, as very ordinary:

Tolkien came back to Oxford, was Rawlinson and Bosworth professor of Anglo-Saxon for twenty years, was then elected Merton Professor of English, Language and Literature, went to live in a conventional Oxford suburb where he spent the first part of his retirement, moved to a non-descript seaside resort, came back to Oxford after his wife died, and himself died a peaceful death at the age of eighty-one. It was the ordinary unremarkable life led by countless other scholars; a life of academic brilliance, certainly, but only in a very narrow professional field that is really of little interest to layman. And that would be that – apart from the fact that during these years when, ‘nothing happened’, he wrote two books which have become world best-sellers, books that have captured the imagination and influenced the thinking of several million readers. It is a strange paradox, the fact that The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are the work of an obscure Oxford professor whose specialisation was the West Midland dialect of Middle English, and who lived an ordinary suburban life bringing up his children and tending his garden.

Or is it? Is not the opposite precisely true? Should we not wonder instead of the fact that a mind of such brilliance and imagination should be happy to be contained in the petty routine of academic and domestic life; that a man whose soul longed for the sound of breaking waves against the Cornish coast, should be content to talk to old ladies in the lounge of a hotel at a middle-class watering place; that a poet in whom joy leapt up at the sight and smell of logs crackling in the grate of a country inn, should be willing to sit in front of his own hearth, warmed by an electric fire with simulated glowing coal? What do we make of that?

Concern for Others

It was part of Tolkien’s “ordinariness” that he had the common touch:

Tolkien always listened, always had a deep concern for the joys and sorrows of others. In consequence, though in many respects a shy man, he made friends easily. He liked to strike up a conversation with a Central European refugee on a train, a waiter in a favourite restaurant, or a hall porter in a hotel. In such company, he was always happy.

That common touch was evident in Tolkien’s concern to answer every letter forwarded to him, especially if it was from a child or an aged person – and Tolkien’s concern to answer every letter thoughtfully.

Tolkien was one of the great intellects of the 20th century – and also a keen gardener, ever concerned for Edith and the children, working on his manuscripts when he could, late at night, and in the early hours of the morning, when everyone else was in bed, with his study invaded by domestic paraphernalia, using a bed as a base on which to type, and retype successive manuscripts of The Lord of the Rings.

Daily Mass-Goer

Tolkien lived in a world which was, if not agnostic, overwhelmingly Protestant. Tolkien was quite open that he was, in Protestant parlance, a Roman Catholic. For long periods of his life, Tolkien attended Mass daily. Tolkien followed the Mass intently, reading the Missal in Latin. All his life Tolkien went regularly to Confession. Tolkien was knowledgeable about his faith, with a profound understanding of both philosophy and theology. Two very important influences on Tolkien were his mother, Mabel, and Fr Francis Morgan, both of whom promoted Tolkien’s muscular Catholicism. One can read Tolkien’s writing without considering his heartfelt Catholicism. Yet to do so is to miss much. A good guide to Tolkien’s philosophy (in an academic sense), subtly influential in his writing, is the American philosopher, Peter Kreeft.

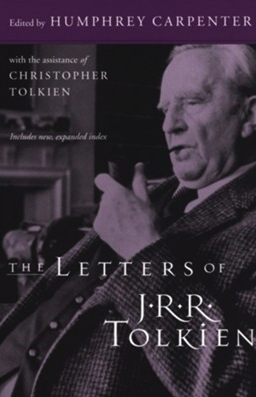

Letters

Humphrey Carpenter’s The Letters of J R R Tolkien is a treasure-trove which enables one to understand his mind so subtle, so refined, so clear.

The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings is, of course, a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in or have cut out, practically all references to anything like “religion”, to cult or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism. However, that is very clumsily put, and sounds more self-important than I feel. For as a matter of fact, I have consciously planned very little; and should chiefly be grateful for having been brought up (since I was eight) in a Faith, that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know; and that I owe to my mother, who clung to her conversion and died young, largely through the hardships of poverty resulting from it.

Frodo

Frodo undertook his quest out of love – to save the world he knew from disaster at his own expense, if he could; and also in complete humility, acknowledging that he was wholly inadequate to the task. His real contract was only to do what he could, to try and find a way, to go as far on the road as his strength and mind and body allowed. He did that. I do not see that the breaking of his mind and will under demonic pressure after torment, was any more moral failure than the breaking of his body would have been – say, by being strangled by Gollum, or crushed by a falling rock.

Eucharist

The only cure for sagging of fainting faith is Communion. Though always Itself, perfect and complete and inviolate, the Blessed Sacrament does not operate completely and once for all in any of us. Like the act of Faith, it must be continuous and grow by exercise. Frequency is of the highest effect. Seven times a week is more nourishing than seven times at intervals…

Guardian Angel

Remember your guardian angel…the bright point of power where that lifeline, that spiritual umbilical cord touches: there is our Angel, facing two ways to God behind us in a direction we cannot see, and to us.

Prayers

If you don’t do so already, make a habit of the ‘praises’’. I use them much (in Latin): the Gloria Patri, the Gloria in Excelsis, the Laudate Dominum; the Laudate Pueri Dominum (of which I am especially fond); and the Magnificat; also the Litany of Loretto (with the prayer, Sub tuum praesidium). If you have these by heart, you never need for words of joy. It is also a good and admirable thing to know the Canon of the Mass…

Church

I, myself, am convinced by the Petrine claims, nor looking around the world does there seem much doubt which (if Christianity is true), is the True Church, the Temple of the Spirit, dying but living, corrupt but holy, self-reforming and rearising. But for me that Church, of which the Pope is the acknowledged head on earth has as chief claim it has (and still does) ever defended the Blessed Sacrament, and given it most honour, and put it (as Christ plainly intended), in the prime place. ‘Feed my sheep’ was His last charge to St Peter; and since His words are always first to be understood literally, I suppose them to refer primarily to the Bread of Life…

Heroism

Tolkien’s sense of life as a struggle against oneself, and as involving struggle between good and evil, is very consistent with a Catholic perspective. Bilbo and Frodo overcome themselves, setting out from the Shire, facing all sorts of dangers, heroically going against the grain, not least against themselves. In some, but not unmitigated ways, Bilbo and Frodo are Christ-like figures as are Gandalf and Aragorn. To say that Bilbo and Frodo, Gandalf and Aragorn are Christ-like figures is not to say that the resemblance is like that of Aslan in CS Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The likeness is far from exact, far from complete. Bilbo and Frodo are more like us, who have to daily overcome ourselves, constantly at risk of falling irretrievably. Despite the overwhelming evil which pervades The Lord of the Rings, there is a goodness which appears, often unexpectedly, and which springs even out of evil. The lembas or waybread provided by the elves, which sustains the wayfarers, despite its apparent lack of substance, elf bread so violently rejected by Gollum, is an allusion to the Eucharist. Bilbo and Frodo are Everyman, enmeshed in their world of comfort and possessions, who have to be led on the journey carrying the Ring to its destruction, but not mastered by the Ring.

Person He Was

Tolkien simply wrote as the person he was – the father of children wanting to read epic fantasy, a philologist with a specialised interest in Old English, an inventor of words, languages, and histories, a faithful Catholic, one of the great writers of the 20th century.

Lifetime of Reading

All this demonstrates that my self-assigned task of reading Tolkien over Summer was misguided. Although I did read most of Tolkien’s work published in his lifetime, there is much more to read, namely the posthumous work edited by Tolkien’s son, Christopher, as well as much more of the commentary. What Tolkien demands is reading and re-reading. Tolkien also demands reading with a commentary if one is to approach Tolkien’s multi-layered meaning. The work published in Tolkien’s lifetime is less in volume and depth than the work edited by Christopher Tolkien published posthumously. And Tolkien has so many layers of meaning that, if one read two or three times, Tolkien’s major works, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings, one would barely have appreciated them. Tolkien offers a lifetime of reading, not a quick read over Summer.

Michael McAuley

25 March 2022