The tradition of celebrating the Red Mass, invoking the Holy Spirit, praying for those whose lives are touched by law, can be traced back to the High Middle Ages. The Red Mass is part of a tradition of thinking about law and justice. The tradition can be traced from when law first appeared in human society. The tradition has high points in the thought of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, in the Bible, and in the writing of St Thomas Aquinas (1225-74). At the heart of this tradition is the inseparable relation of law and justice.

Law and Justice

This relation of law and justice is exemplified in the judicial oath – to do justice according to law, to all manner of persons, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will. The decision of the High Court of Australia in Mabo (No 2)(1975) 192 CLR 1 illustrates this tradition.

Terra Nullius

In my first year at Sydney University, I was taught that in 1788 the English settlers brought with them English law insofar as it was applicable to the circumstances of the colony of New South Wales. Australia was virtually uninhabited (terra nullius), and so English law came with the settlers. Even at that time I considered this to be wrong.

Mabo

Without analysing the entirety of the reasons of the six members who formed the majority in Mabo, the High Court held (subject to certain qualifications) that the Meriam people from the Torres Strait were entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the lands of the Murray Islands.

Universal Human Rights

Brennan J (as he then was) commented:

The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country…Whatever the justification advanced in earlier days for refusing to recognize the rights and interests in land of the indigenous inhabitants of settled colonies, an unjust and discriminatory doctrine of that kind can no longer be accepted. The expectations of the international community accord in this respect with the contemporary values of the Australian people…The common law does not necessarily conform with international law, but international law is a legitimate and important influence on the development of the common law, especially when international law declares the existence of universal human rights. A common law doctrine founded on unjust discrimination in the enjoyment of civil and political rights demands reconsideration. It is contrary both to international standards and to the fundamental values of our common law to entrench a discriminatory rule which, because of the supposed position on the scale of social organization of the indigenous inhabitants of a settled colony, denies them a right to occupy their traditional lands.

Life On Murray Islands

The factual background to Mabo is outlined by Brennan J:

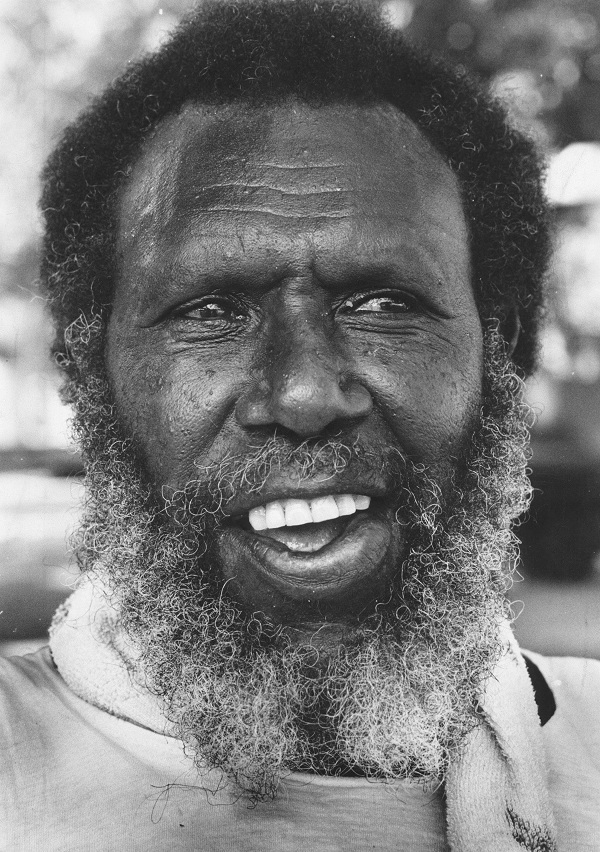

The Meriam people were in occupation of the Islands for generations before the first European contact. They are a Melanesian people (perhaps an integration of differing groups) who probably came to the Murray Islands from Papua New Guinea. Their numbers have fluctuated, probably no more than 1000, no less than 400.

Some of the features of life in the Murray Islands at the time of first European contact, at the end of the 18th century, are described by Moynihan J. in his findings in the present case:

“… The people lived in groups of huts strung along the foreshore and immediately behind the sandy beach. They still do although there has been a contraction of the villages and the huts are increasingly houses. The cultivated garden land was and is in the higher central portion of the island. There seems however in recent times a trend for cultivation to be in more close proximity with habitation. The groups of houses were and are organised in named villages. It is far from obvious to the uninitiated, but is patent to an islander, that one is moving from one village to another. The area occupied by an individual village is, even having regard to the confined area on a fairly small island which is in any event available for ‘village land’, quite small. Garden land is identified by reference to a named locality coupled with the name of relevant individuals if further differentiation is necessary. The Islands are not surveyed and boundaries are in terms of known land marks such as specific trees or mounds of rocks. Gardening was of the most profound importance to the inhabitants of Murray Island at and prior to European contact. Its importance seems to have transcended that of fishing … Gardening was important not only from the point of view of subsistence but to provide produce for consumption or exchange during the various rituals associated with different aspects of community life.

Aborigines

That the Court’s decision in Mabo was significant, not only for Torres Strait islanders, but for Australia’s original inhabitants generally is evident from the reasons of Deane and Gaudron JJ:

…the numbers of Aboriginal inhabitants far exceeded the expectations of the settlers. The range of current estimates for the whole continent is between three hundred thousand and a million or even more. Under the laws or customs of the relevant locality, particular tribes or clans were, either on their own or with others, custodians of the areas of land from which they derived their sustenance and from which they often took their tribal names. Their laws or customs were elaborate and obligatory. The boundaries of their traditional lands were likely to be long-standing and defined. The special relationship between a particular tribe or clan and its land was recognized by other tribes or groups within the relevant local native system and was reflected in differences in dialect over relatively short distances. In different ways and to varying degrees of intensity, they used their homelands for all the purposes of their lives: social, ritual, economic. They identified with them in a way which transcended common law notions of property or possession.

In the context of the above generalizations, the conclusion is inevitable that, at the time of the establishment of the Colony of New South Wales in 1788, there existed, under the traditional laws or customs of the Aboriginal peoples in the kaleidoscope of relevant local areas, widespread special entitlements to the use and occupation of defined lands of a kind which founded a presumptive common law native title under the law of a settled Colony after its establishment.

The Mabo decision led to the enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) which established the Native Title Tribunal to make native title determinations. As Sean Flood in Mabo: a Symbol of Struggle (2021) has made clear, the injustices suffered by Australia’s first peoples are far from having been completely addressed by Mabo. There is much more to be done.

Franklin on Mabo

To understand Mabo, one ought read James Franklin’s Corrupting the Youth: a History of Philosophy in Australia (2003). There, Franklin discusses the impact of Aquinas’ understanding of the relation of law and justice on the majority in the High Court, in particular, Justices Brennan, Deane, Toohey and Gaudron. There, Franklin argues that the natural law philosophy of ethics, stressing objective principles of justice, has survived and flourished in the nourishing habitat of the Australian courts. According to Franklin:

…the most dramatic outcome of Catholic philosophy in recent times has been the High Court’s Mabo judgment on Aboriginal land rights. The fundamental issue in the case is the conflict between the existing law based on the principle of terra nullius, and what the judges took to be the objective principles of justice.

Franklin refers to the approach of Sir Gerard Brennan, the writer of the first Mabo judgment and Mason CJ’s successor as Chief Justice:

His theory of the relation of morality and law is that of the Catholic natural law school. In earlier works he had praised such Catholic legal heroes as Thomas More, well known for his stand on the conflict of law and morality, and the colonial Irish lawyers, Therry and Plunkett, whose ‘impartial enforcement of the law’ secured the convictions of the perpetrators of the Myall Creek Massacre. He also commented favourably on Higgins’ adoption in the Harvester judgment of the phrase ‘reasonable and frugal comfort’ as the standard which a basic wage ought to support, from an outside moral source, an encyclical of Pope Leo XIII. Lawyers, he also said, have moral duties beyond simply applying the law they find in place – ‘If the law itself is an obstacle to justice, the duty of the Christian lawyer extends to seeking its reform.’

Moral Values Inform the Law

Most remarkably in a speech on ‘Commercial Law and Morality’, Sir Gerard Brennan said:

Moral values can and manifestly do inform the law…The stimulus which moral values provide in the development of legal principle is hard to overstate, though the importance of the moral matrix to the development of judge-made law is seldom acknowledged. Sometimes the impact of the moral matrix is obvious, as when notions of unconscionability determine a case. More often the influence of common moral values goes unremarked. But whence does the law derive its concepts of reasonable care, of a duty to speak, of the scope of constructive trusts – to name but a few examples – save from moral values translated into legal precepts?’

According to Franklin, the complex maze of rules that make up commercial law may seem an inhospitable domain for moral imperatives, but the opposite is true according to Brennan. It is for the commercial lawyer to determine the moral purpose behind each abstruse rule, and advise his client’s conscience of what is just in the circumstances, not merely what he can legally get away with.

Darkest Aspect of Australian History

Elsewhere, Franklin quotes Deane and Gaudron JJ:

…the circumstances of the present case make it unique… the…propositions in question provided the legal basis for the dispossession of the Aboriginal peoples of most of their traditional lands. The acts and events by which that dispossession in legal theory was carried into practical effect constitute the darkest aspect of the history of this nation. The nation as a whole must remain diminished unless and until there is an acknowledgment of, and retreat from, those past injustices.

Aquinas

St Thomas Aquinas lived in a substantially farming society ruled by princes and kings. Since Aquinas’ time there has been:

- enormous increase in population

- urbanisation

- globalisation

- scientific and technical advance

- Industrialisation

- mass transportation

- mass communication

- space travel

- sophisticated and diverse financial institutions

- sophisticated medical care

- separation of powers

- democratically elected legislatures

- formal specification of human rights,

- development of international institutions

- development of elaborate hierarchies of national courts, involving highly specialised lawyers, as well as international courts,

- development of highly specialised bureaucracies serving government,

- development of professional defence forces with very destructive means of fighting wars

Significance

How can Aquinas’ thinking about law and justice be of any relevance to our very different society? Even a cursory reading of the Summa Theologiae, in particular, the Treatises on Law, on Justice, and on Injustice, demonstrate a parallel between the Gothic cathedrals of the High Middle Ages and Aquinas’ writing on law and justice. As the legal historian, Harold Berman, comments, both were constructed and reconstructed with eyes both to the past and to the future. They speak of a perennial reality.

Roman Lawyers

The background to Aquinas is to be found in secular writers, for instance, in the writing of the Roman lawyers Gaius (c130-180), and Ulpian (170-223? 238?). The admonition of Ulpian – juris praecepta sunt haec: honeste vivere, alterum non laedere, suum cuique tribuere – the precepts of the law are to live honourably, not to harm any other person, to render to each his due – is just as applicable today as in the time of Ulpian.

Division of Roman Empire Between East and West

In 330 Constantine shifted the capital of the Roman Empire to what was called Constantinople, Istanbul in modern day Turkey. The Roman Empire had two lungs, the east and the west. When the western Roman empire collapsed under the barbarian hordes, the east continued for another thousand years. The Roman Empire in the east eventually collapsed in 1453 with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. 476 is usually designated as the year the Roman Empire finally fell in the West as a result of repeated barbarian invasions. The division between east and west remains significant for contemporary European politics, and for religious and intellectual life.

Justinian

Under the Roman Emperor in the east during the reign of Justinian (482-565), were produced the Digest (533), the Code (534), the Institutes, the Novels, all of which constitute Justinian’s Corpus Iuris Civilis. Other sources for Aquinas’ writing on law and justice include the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC), the Roman advocate Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), St Augustine (354-430 AD), and St Isidore of Seville (570-636).

Roman law fell into oblivion in western Europe, but was gradually recovered, about the time of St Thomas Aquinas, beginning in Bologna at the end of the eleventh century.

Church Law

The Decretum, or Concordantia Discordantium Canonum, of Gratian, a monk and the father of canon law, published in 1141, is a systematic statement of the law of the Western Church. Also important in the development of the law in the High Middle Ages are the Decretals of Gregory IX (1234). These are amongst the sources upon which St Thomas Aquinas drew for his writing on law and justice.

Origins of Modern European Law

For a masterful presentation of the origins of modern European law, one ought go to Harold Berman’s Law & Revolution: the Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (1983), and Law & Revolution: the Impact of the Protestant Reformations on the Western Legal Tradition (2003). Berman summarises the relationship between law and Christianity which is the historical background to Aquinas’ Treatise on Law:

With the conversion of the Roman emperors to Christianity in the fourth century, the Church came to operate within the power structure. Now it faced a quite different aspect of the question of the relationship between law and religion – namely, whether the emperor’s acceptance of the Christian faith had anything positive to contribute to his role as legislator. The answer given by history was that the Christian emperors of Byzantium considered it their Christian responsibility to revise the laws, as they put it, ‘in the direction of greater humanity.’ Under the influence of Christianity, the Roman law of the postclassical period reformed family law, giving the wife a position of greater equality before the law, requiring mutual consent of spouses for the validity of marriage, making divorce more difficult (which, at that time, was a step towards women’s liberation!) and abolishing the father’s power of life or death over his children; reformed the law of slavery, giving a slave the right of appeal to a magistrate if a master abused his powers and even, in some cases, the right to freedom if the master exercised cruelty, multiplying modes of manumission of slaves, and permitting slaves to acquire rights by kinship with freemen, and introduced a concept of equity into legal rights and duties generally, thereby tempering restrictiveness of general prescriptions. Also, the great collections of laws compiled by Justinian and his successors in the sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries were inspired, in part, by the belief that Christianity required that the law be systematised as a necessary step in its humanisation. These various reforms were, of course, attributable not only to Christianity, but Christianity gave an important impetus to them as well as providing the main aetiological justification. Like civil disobedience, law reform ‘in the direction of greater humanity’ remains a basic principle of Christian jurisprudence derived from the early experience of the Church.

Reforms

In contrast to the Byzantine emperors, who inherited the great legal traditions of pagan Rome, the rules of the Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples of Europe during roughly the same era (from the fifth to the tenth centuries), presided over a legal regime consisting chiefly of primitive tribal customs and rules of the blood feud. It is more than coincidence that the rulers of many of the major tribal peoples, from Anglo-Saxon England to Kievan Russia, after their conversion to Christianity promulgated written collections of tribal laws and introduced various reforms, particularly in connection with family law, slavery, and protection of the poor and oppressed, as well as in connection with Church property and the rights of clergy. The laws of Alfred (about A.D. 890) start with a recitation of the Ten Commandments and excerpts from the Mosaic Law; and in restating and revising the native Anglo-Saxon laws Alfred includes such general principles as: ‘doom [i.e. judge] very evenly; doom not one doom to the rich, another to the poor; nor doom one to your friend, another to your foe.’

Limiting Violence

The Church in those centuries, subordinate as it was to emperors, kings, and barons, sought to limit violence by establishing rules to control blood feuds; and, in the tenth and eleventh century, the Great Abbey of Cluny, with his branches all over Europe, even had some success in establishing the so-called Peace of God, which exempted from warfare, not only the clergy, but also the peasantry, and the so-called ‘Truce of God’, which prohibited warfare on the weekends. Here, too, are influences of religion and law that have bearing for our time.

Civilised Values Crushed by Hostile Environment

Nevertheless, despite the reforms and innovations of Christian kings and emperors, the prevailing law of the West remains – prior to the twelfth century – the law of the blood feud and trial by battle, and ordeals of fire and water, and ritual oaths. There were no professional judges, no professional lawyers, no law books, either royal or ecclesiastical. Custom reigned – tribal custom, local custom, feudal. In the households of kings and in the monasteries, there was civilisation to a degree; but, without a system of law, it was extremely difficult to transmit civilisation from the centres to the localities. To take one for example: the Church preached that marriage is a sacrament which cannot be performed without the consent of the spouses, but there was no effective system of law by which the Church could overcome the widespread practice of arranging marriages between infants. Not only were civilised values crushed by a hostile environment, but the Church itself was under the domination of the same environments: lucrative and influential clerical offices were bought and sold by feudal lords, who appointed brothers and cousins to be bishops and priests.

New Kinds of Law

In the latter part of the eleventh and first part of the twelfth century, there took place in the West a great revolution which resulted in the formation of the visible, corporate, hierarchical Church, a legal entity independent of emperors, kings and feudal lords, and subordinate to the absolute monarchical authority of the bishop of Rome. This was the Papal Revolution, of whose enormous significance mediaeval historians, both inside and outside the Catholic Church, are becoming increasingly aware. It led to the creation of a new kind of law for the Church, as well as new kinds of law for the various secular kingdoms.

Previously the relationship between the spiritual and secular realms had been one of overlapping authorities, with kings (Charlemagne and William the Conqueror, for example) calling Church councils and promulgating new theological doctrine and ecclesiastical law, with popes, archbishops, bishops and priests being invested in their offices by emperors, kings and lords. In 1075, however, Pope Gregory VII proclaimed the complete political and legal independence of the Church and, at the same time, proclaimed his own supreme political and legal authority over the entire clergy of Western Christendom. It took 45 years of warfare between the papal and the imperial parties – the Wars of Investiture – and in England it took the martyrdom of Thomas Becket before the papal claims were established (albeit with some substantial compromises).

Canon Law First Modern Legal System

The now visible, hierarchical, corporate Roman Catholic Church needed a systematic body of law, and in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries this was produced – first in a great treatise written about 1140 by the Italian monk Gratian, and 80 years later, after a succession of jurist-popes had promulgated hundreds of new laws, and after Pope Gregory IX’s Decretals of 1234. The Decretals remained the basic law of the Roman Church until 1917.

Of course, there had been ecclesiastical canons long before Gratian, but they consisted of miscellaneous scattered decisions, decrees, teachings, et cetera, mostly of a theological nature, pronounced by various church councils and individual bishops and occasionally gathered in chronologically arranged collections. There were also traditional procedures and ecclesiastical tribunals. However, there was no systematised body of ecclesiastical law, criminal law and family law, inheritance law, property law, or contract law, such as was created by the canonists of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The canon law of the later Middle Ages, which only today, eight centuries later, is being called into question by some leading Roman Catholics themselves, was the first modern legal system of the West, and it prevailed in every country in Europe. The canon law governed virtually all aspects of the lives of the Church’s own army of priests and monks, and also a great many aspects of the lives of the laity. The new hierarchy of Church courts had exclusive jurisdiction over lay men in matters of family law, inheritance, and various types of spiritual crimes, and, in addition, it had concurrent jurisdiction with secular courts over contracts (whenever the parties made a ‘pledge of faith’; property, whenever ecclesiastical property was involved – and the Church once owned one fourth to one third of the land of Europe), and many other matters.

Emergence of Secular Law

The canon law did not prevail alone, however. Alongside it there emerged various types of secular law, which just at this very time, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, began to be rationalised and systematised. In about 1100, the Roman law of Justinian, which had been virtually forgotten in the West, for five centuries, was rediscovered. This rediscovery played an important part in the development of the canon law, but it also was seized upon by secular rulers who resisted the new claims of the papacy. And so in emulation of the canon law, diverse bodies of secular law came to be created by emperors, kings, great feudal lords, and also eventually in the cities and boroughs that emerged in Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, as well as among merchants trading in great international affairs. The success of the canon law stimulated secular authorities to create their own professional courts and a professional legal literature, to transform tribal, local, and feudal custom, and to create their own rival legal systems to govern feudal property relations, crimes of violence, mercantile transactions, and many other matters.

What A Modern Legal System is Like

Thus, it was the Church that first taught Western man what a modern legal system is like. The Church first taught that conflicting customs, statutes, cases and doctrines may be reconciled by analysis and synthesis. This was the method of Abelard’s famous ‘sic et non’ (Yes and No), which lined up contradictory texts of holy Scripture – the method reflected in the title of Gratian’s Concordance of Discordant Canons. By this method the Church, in reviving the study of the obsolete Roman law, transformed it by transmuting its complex categories and classifications into abstract legal concepts. These techniques were derived from ‘the principle of reason’ as understood by theologians and philosophers in the twelfth century, as well as by the lawyers.

Conscience

The Church also taught the principle of conscience – in the corporate sense of the term, not the modern individualist sense: that the law is to be found not only in scholastic reason but also in the heart of the law giver or judge. The principle of conscience in adjudication was first stated in eleventh century France which declared that the judge must judge himself before he may judge the accused, but he must, in other words, identify himself with the accused, since thereby (it was said) he will know more about the crime than the criminal himself knows.

A new science of pleading and procedure was created in the Church courts, and later in secular courts as well (for example, the English Chancery), informing the conscience of the judge. Procedural formalism was attacked. (In 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council effectively abolished trials by ordeal throughout Europe by forbidding clergy to participate in them). The right to direct legal representation by professional lawyers and the procedure for interrogation by the judge according to carefully worked out rules were among the new institutions created to implement the principle of conscience.

Equity

Conscience was associated with the idea of the equality of the law, since in conscience all litigants are equal; and from this came equity – the protection of the poor and the helpless against the rich and powerful, the enforcement of relations of trust and confidence, and the granting of so-called personal remedies such as injunctions. Equity, as we noted earlier, had been part of the postclassical Roman law, but it was now for the first time made systematicand special procedures were devised for invoking and applying it.

Nature of Law

St Thomas Aquinas says in his Treatise on Law, law is an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by the authority having care of the community, and promulgated.

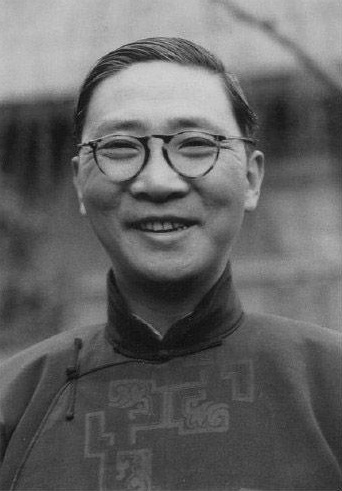

John Wu

John Ching-Hsiung, later known as John C H Wu (1899-1986), was Chief Justice of the Provisional Court of Shanghai, and later Minister of Justice in the Chinese Government before its fall to communism in 1949. Wu was the principal author of the Constitution of the Republic of China adopted in 1946. Wu corresponded over a long period with US Supreme Court Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, and later wrote a scholarly work on Holmes’ thought.

Fountain of Justice

Wu wrote a book, Fountain of Justice: a Study in Natural Law (1955). There, Wu considers the relationship between natural law and common law. Wu represents the path China may have taken until 1949 when Mao Tse-tung and the communists took power. Wu represents in his life and writings the universality of natural law.

Eternal Law

According to Aquinas, eternal law is the idea of things conceived by God, the plan of Divine Providence. Since God does not conceive ideas as we do in time, God’s idea of things is eternal. Eternal law is the governing idea in the mind of God, such that all law, insofar as it is law, is a participation in eternal law.

Aquinas’ understanding of law involves analogy – eternal law, natural law, human law. Each is law, but each is different. Hence analogy.

Workers Compensation Act 1987, s 151Z

As lawyers the danger is that we become experts in s151Z of the Workers Compensation Act 1987 (NSW), and that is our world. We cannot move beyond s151Z – at least until the section is repealed! or the High Court upturns the conventional understanding! There is a universe of understanding about law which narrow technical lawyers miss! As Wu points out, law is not merely a technique for making a living! nor mere technicality regardless of justice. There is more to life than being a partner in a first-tier commercial firm doing the best work! and making the best money! more than being a technician! There is more to law than the mundane, the pedestrian!

Grand Way

According to Wu, the way to teach law is in the grand way, reaching beyond the mundane, beyond the pedestrian, beyond mere technicality! Wu comments laconically:

…even when a lawyer is doing the journey-man’s work of his profession, the Furies are at work in him although he does not understand this. It is usually the unconscious philosophy of a man which is the most doctrinaire and stubborn.

Hence the importance of possessing a philosophy of law which is possessed of reality, a philosophy of law and justice which applies in all times, in all places, in all circumstances. Aquinas’ writing on law and justice transcends the society of his time. Aquinas writes for all time.

Distinction between Eternal, Natural and Human Law

Adopting the perspective of a journeyman lawyer, Wu explains the distinction between the eternallaw, natural law and human law:

The internal law, the natural law and human law, form a continuous series. The whole series may be compared to a tree, the eternal law for its roots, the natural law for its trunk, and the different systems of human law for its branches. Wherever the soil is not too thin and the climate favourable, the tree sends forth its splendid flowers of justice and equity and yields the fruit of peace and order, virtue and happiness. Indeed, peace is the fruit of justice. Formally, the eternal law and the natural law belong to higher orders than human laws; but materially, humanlaw is richer and furnishes a more interesting field of study, because it embodies, ‘within the limits of its capacity,’ part of the natural law together with certain positive or conventional rules and measures which vary with time and circumstance.

Natural Law

Natural law is, according to Aquinas, a sharing in the eternal law by intelligent creatures. Aquinas quotes St Paul’s Letter to the Romans:

When the Gentiles who have not the law do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law. They show that what the law requires is written on their heart, while their conscience also bears witness and their conflicting thoughts accuse or perhaps excuse them on that day when, according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Jesus Christ.’

The Ignatius Bible, reflecting the tradition of the Church, comments that a good moral conscience prevails upon us to do good and avoid evil in light of objective moral norms. It renders a practical judgment that determines whether or not our actions reflect God’s law. A well-formed conscience is the voice of God speaking within us, guiding us, fulfilling God’s will with concrete acts in our particular circumstances.

Written in the Mind and Heart

The natural law is written in the mind and heart of every person. Just as we can come to know God through natural means, we can also discern the fundamentals of objective morality, which is a sharing in God’s eternal law. This enlightenment gives us a natural sense of good and evil. Knowledge of the moral law forms the basis for a good conscience that guides us in our moral choices. Because of this innate knowledge, even a nonbeliever can lead a virtuous life and keep the Commandments even if never introduced explicitly to the Ten Commandments. Meanwhile, those who have faith in God and know the moral law, but transgress that law will be held more accountable.

While all creatures participate in Divine Providence, intelligent creatures participate in the eternal law more perfectly by use of reason. Thus, what is distinctive in natural law as regards humans is reason.

Synderesis

Synderesis is concerned with our knowledge of the first principles of natural law. The first principle of natural law is – good is to be done and pursued, evil is to be avoided. Other principles of natural law or practical reason include:

- evil is not to be done for the sake of the good;

- emotional desires and responses are subject to human good;

- habits of doing good are to be fostered;

- the common good is to be respected and promoted.

New Natural Law Theory

The New Natural Law theorists, most notably the Australian, John Finnis, have contributed greatly to our understanding of natural law, if only by encouraging a dialogue as to natural law. John Finnis’ seminal work is Natural Law and Natural Rights (1980). The American Journal of Jurisprudence (formerly the Natural Law Forum) is a convenient location for much debate about the New Natural Law Theory (NNLT). The Natural Law Reader edited by Jacqueline A Laing and Russell Wilcox provides a very good introduction to the diversity of natural law thinking. There are many approaches to natural law, many different expositions of natural law theory, and no single approach is beyond argument.

Law Without Justice

Wu, echoing Aquinas, argues that the force of a law, a judicial decision, or an administrative act, depends on the extent of its justice. Justice means nothing more than conformity with natural law. Law contrary to reason, law without justice, tyrannical law, is the mere semblance of law. This understanding underpins the reasoning of the majority in Mabo.

Lawlessness

According to Wu, the fact that such and such a thing has been done by certain states at certain periods of their history does not turn lawlessness into law. Wu, writing in 1955, had plenty of personal experience of lawless activity by states. The history of European (and later Japanese) imperialism in China is a history of injustice. Wu refers to St Augustine’s question: “Without justice, what are kingdoms but gangs of robbers?”

In my opinion, a gap in Aquinas’ account of law as involving commanding, forbidding, permitting, and punishing is that Aquinas overlooks the role of human law in coordinating activity within complex society, and providing services to citizens which enhance everyday life.

Other Aspects

Other aspects of Aquinas’ thought on law include:

- There is a natural tendency to act in accordance with reason, with virtue; to acknowledge the goods to which the person has a tendency – life, work, play, study, friendship, marriage, religion, truth, goodness, beauty; to acknowledge the virtues which make for human happiness – prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance.

- The first principles of practical reason (good is to be done and pursued, evil to be avoided, etc.) are the same for everybody, as are the secondary principles (which forbid disregard for the life of others, the family relations of others, the property of others, lying, detraction, and so on).

- When it comes to specific actions there may reasonably be many different approaches. There are legitimate different perspectives. Human freedom is to be respected. Vive la difference! Natural law is not a straitjacket!

- The principles of natural law are the same for all. But the more one considers particular situations, the greater the room for particular perspectives.

Human Law

- Human law can be a conclusion from natural law. “You must not commit murder” can be inferred from “You must do harm to nobody”. Alternatively, human law may be a determination, a shape given to a general idea, as when an architect designs a house in a particular way – or when the proposition that crime must be punished is applied in a particular way.

- Human law applies natural law principles to particular circumstances. As human circumstances are multivarious, so judgments can vary, perspectives can vary; so human laws can be very different, and yet consistent with natural law.

- Human law cannot forbid or punish all wrong-doing, for were it to do away with all evils it would also take away much that is good and so hinder what the common good requires. Human law permits many things, not as approving them, but as being unable to control them.

Virtue

- A polity cannot flourish unless its citizens are virtuous, or at least those in leading positions are virtuous.

- The effect of a just law, consistent with human reason, is to make its subjects good. Law ought encourage human virtue.

- While law ought encourage human virtue, nevertheless law is laid down for the great number of people, of which the majority have no high standard of morality. Therefore, it does not forbid all vices, from which upright men can keep away, but only those grave ones which the average man can avoid, and chiefly those which do harm to others and have to be stopped if human society is to be maintained, such as murder and theft and so on.

- Wrong persuasion, emotion, perverse custom or habit can lead persons to wrong conclusions. Aquinas gives the example of those who consider robbery permissible, although it is contrary to natural law. An example of this is Elizabeth I’s support in the 16th century of the pirates Sir Francis Drake and John Hawkins.

- Within human beings there is a natural bent or tendency to what is good, which is spoilt by vice, with the natural knowledge of what is right darkened by unrestrained emotion and habits of sin.

Legislature

- Law is better enacted by the legislature rather than left to the decision of judges in individual cases. Aquinas regards judges as likely to be swayed by the particular case before them, whereas the legislature can take a broader view. Laws enacted by the legislature can be framed after mature consideration having regard to the generality of things, as well as looking to the future, whereas the judge has only the facts of the particular matter before him or her.

- Human law should be fair, possible, consistent with the customs of the country, befitting time and place, clearly stated.

Just & Unjust Laws

- Human law binds in conscience provided it is just.

- A just law is directed to the common good, does not exceed the lawgiver’s power, and imposes burdens equitably.

- An unjust law is not directed to the common good as when a ruler taxes his subjects for his greed or vanity rather than the common good; or when he enacts a law beyond the power committed to him; or when laws are inequitable. Such are outrages rather than law.

- An unjust law will not bind in conscience except perhaps to avoid scandal or riot. On the latter account, a person may be obliged to yield the person’s right.

Mixed Government

- Aquinas accepts Aristotle’s distinction of governments between monarchy, aristocracy and polity with each “type” having a corresponding corruption where it falls away from reason, no longer directed to the common good. For instance, the corruption of monarchy is tyranny, the corruption of aristocracy is oligarchy, etc. Aquinas favours a mixed form of government which has monarchical, aristocratic and popular elements.

- All are subject to law.

Generality of Cases

- Laws are made for the generality of cases. It is not possible to envisage every situation. Aquinas gives the example of a law of a medieval city that the gates are to be closed at night. But say some citizens are being pursued by an enemy. If the gates are kept closed, the citizens will be killed with great loss to the city. Hence, despite the law, the gates may be opened momentarily to enable the citizens to escape. In considering such situations one looks to the lawmaker’s intention which is to look to the good of the city, permitting one to act beside the letter of the law. If there is time, the decision ought be made by the governing authority, but Aquinas acknowledges a decision may have to be made at once. In such a case Aquinas acknowledges necessity knows no law.

Equity

- Laws are to be read with equity. In this regard Aquinas quotes Justinian:

No reason in law nor goodwill in equity brooks that we should put harsh interpretations on healthy measures brought in for men’s welfare, and take them to a grimness that conflicts with the benefits they bring.’

Aquinas continues:

Since he cannot envisage every individual case, the legislator frames the law to fit the majority of cases, its purpose being to serve the common welfare. So that if a case crops up where its observance would be damaging to that of common interest, then it is not to be observed…He who acts counter to the letter of the law in case of need is not questioning the law itself, but judging the particular issue confronting him, where he sees the letter of the law is not to be applied. The man who follows the law maker’s intention is not interpreting the law simply speaking as it stands, but setting it in its real situation… Nobody is so wise as to be able to forecast every individual case, and accordingly, he cannot put into words all the factors that fit the end.

- Elsewhere Aquinas argues:

Now it happens at times that some precept is for the people’s benefit. In some cases it is not helpful for this particular person or in this particular case, either because it stops something better happening or it brings in some evil … To leave the decision to anybody’s discretion would be dangerous, except, perhaps, where there is evidently an emergency…Therefore he whose office it is to rule the people has the power to grant dispensation from the human laws that rest on his authority, so that in respect of persons and cases where the law is wanting, he may give leave for it not to be observed.

Passing Judgment

- Passing judgment is an act of justice. Judgment is not to be based on suspicion. A person should be given the benefit of the doubt. Judgment should normally be according to the written law though, where application of the written law would work injustice, equity should prevail. Judges should only give judgment in accordance with their authority.

Custom

- When human laws are changed there is a loss, as the change in law provokes uncertainty. Custom is a source of law. Aquinas argues:

All law proceeds from the reason and will of the law-giver; divine and natural law from the intelligent will of God, human law from the will of man regulated by reason. Man’s reason and will in matters of practice are manifested by what he says, and by what he does as well; each carries into execution what he has chosen because it seems to him good.

As manifesting interior concepts and motions of the human mind, it is clear that words serve to alter a law as well as express its meaning. So also by repeated deeds, which set up the custom, a law can be changed and explained, and also a principle can be established which acquires the force of law, and this because what we inwardly mean and want is most effectively declared by what outwardly and repeatedly we do. When anything is done again and again it is assumed that it comes from the deliberate judgment of reason.

Framework for Discourse

Aquinas’ Treatise on Law provides a realistic, indeed perennial, framework for discourse about law and justice, as much applicable in Europe in the High Middle Ages, as in China, as in Australia, as in Africa, as in the Middle East, as in Asia, as in the Americas today. Aquinas’ theory of law is for all times, all places, all circumstances.

Secular Expression

While Aquinas’ natural law theory developed in part in the context of a theological understanding of reality, that theory of natural law is capable, as Berman outlines, of a secular expression:

Indeed, a secular and rational theory of natural law is not only entirely possible but is the most widespread form which current natural law theory takes. The morality inherent in law itself, the principles of justice which are implicit in the very concept of adherence to general rules, may be perceived by moral philosophers without reference to religious values or religious insights. Also, anthropologists are able to show by empirical observation that no society tolerates indiscriminate lying, stealing, or violence within the in-group, and indeed, the last six of the Ten Commandments, which require respect for parents and prohibit killing, adultery, stealing, perjury and fraud, have some counterpart in every known culture. In fact, many natural law theorists consider a religious explanation of law to be superstitious and dangerous. Such theorists are able to demonstrate by reason and observation alone that basic legal values and principles correspond to human nature and to the requirements of a social order. Contracts should be kept; injury should be compensated; one who represents another should act in good faith; punishment should not be disproportionate to the crime. These and a host of other principles reflect what reason tells us is morally right and what in virtually all societies is proclaimed to be legally binding.

The theory of law and justice, exemplified by St Thomas Aquinas, embraced by the Chinese lawyer, John C H Wu, which influenced some members of the majority in Mabo, is an aspect of the same tradition as the Red Mass.

Michael McAuley

18 February 2022