Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), the 700th anniversary of whose death we celebrate this year, lived in Florence, a wealthy and tightly packed Italian city of 100,000 people riven by political factionalism. Like political factionalism in every age, the rivalry between the Guelphs (allied with the popes) and the Ghibellines (allied with the Holy Roman emperors) was driven by personalities and desire for power. Any lofty statement of ideals was belied by self-interest, and rancour.

In 1215 the break-up of a proposed marriage between two Florentine families led to a lasting blood feud. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (although set in Verona) gives some sense of factionalism in Florence. In 1220, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen, also King in southern Italy, commenced trying to assert power in northern Italy.

Italian Politics

Italian politics, at the time, involved conflict between the popes and the Holy Roman Emperor (modern day Germany). The popes controlled Rome and central Italy. The Holy Roman Emperor controlled the south of Italy, and sought to exercise greater control of the city-states of northern Italy, bringing him into conflict with the popes. The city-states of northern Italy were in constant conflict amongst themselves.

Illustrative of the irrationality of political factionalism during Dante’s lifetime, the Florentine Guelphs split in 1299 between Blacks and Whites. Dante was a White Guelph. Both sides appealed to Pope Boniface VIII, although the dispute had little to do with religion. Pope Boniface VIII supported Dante’s opponents, the Black Guelphs.

Dante

Dante was born in 1265 into a Guelph merchant family. In 1300 Dante became a prior (part of the governing council) of Florence. As a young man, Dante wrote love poetry, the best of which is in the Vita Nuova, an intricate collection of poems and commentary in honour of a young woman, Beatrice. In January 1302, as a result of political machinations in which Pope Boniface VIII was involved, Dante was condemned and exiled from Florence. In 1304 Dante broke from the White Guelphs.

Epic

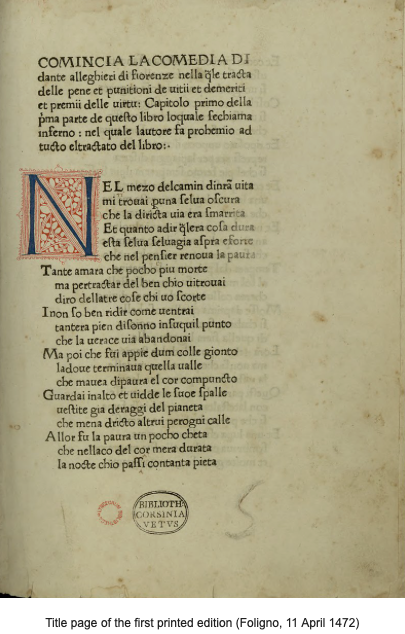

Commedia (only after Dante’s death was it renamed by a publisher Divina Commedia) is an epic, called a Commedia because it has a happy ending in Paradiso. While many read only Inferno, forgetting Purgatorio and Paradiso, this, according to Dorothy Sayers, is like restricting one’s vision of Paris to its sewers! To understand the sweep and balance of Divina Commedia, one must read the whole work.

Greatest Work of Italian Literature

The central figure of Divina Commedia is Dante himself. The epic journey, reminiscent of Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid, commences on Good Friday 1300, at a time when Dante finds himself in a “dark wood”. Divina Commedia is written in Italian at a time when most writing was in Latin. Divina Commedia is the greatest work of Italian literature.

Dante brings to Divina Commedia an immense knowledge of history and culture, of Greek and Roman mythology, of Christian sources, in particular Sacred Scripture, the Fathers of the Church (for instance, St Augustine’s Confessions), St Thomas Aquinas. The cosmology of Dante’s world is Ptolemaic with the earth at the centre. The characters in Divina Commedia are a mixture of historical and mythological, as well as personalities drawn from Florence and Italy in the high middle ages. To play a part in Divina Commedia one had to be a historical character dead by 1300, or a mythological character.

Reading Divina Commedia

Given modern ignorance of history, mythology, Florence, indeed Italy, in the high middle ages, ignorance of Sacred Scripture, the Fathers of the Church, and the great Christian writers such as St Thomas Aquinas, most editions of Divina Commedia come with notes. To me the best way to read Divina Commedia is to read an individual Canto quickly, skim the notes for what is most important, and then move on to the next Canto. An accompanying introduction to Dante and his world is of great assistance, particularly if it contains diagrams and tables explaining Dante’s cosmology, and the journey through Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. I have yet to find an edition of Divina Commedia with which I am entirely happy. To my mind, a common issue with many editions of Commedia is use of archaic English, and use of end-notes rather than footnotes.

Optimism

Divina Commedia is a work of great optimism, the heart of which is love, the transcendent love of God. Purgatorio expresses the hope of repentant sinners culminating in the love of the Paradiso. Sin involves a freely chosen turning away from God, a choice to pursue a desire for some created thing which can never satisfy, a misbegotten love directed to self. Sin is self-defeating, self-destructive. It hurts, indeed destroys, us. So, the sinners in Inferno have created their own hell by freely chosen self-destructive choices in which they persist without repentance. The sinners in Inferno blame others for their predicament. They lack insight into their own behaviour. They are self-obsessed.

The sinners in Purgatorio have repented, have rejected self-centred, self-destructive desire, in favour of the love of God, the only love which can fulfil. The repentant sinners in Purgatorio have the insight the sinners in Inferno lack. Only in Paradiso has self-giving love been made perfect. Inferno or Hell is the place where unrepentant sinners dwell. The division of Hell is the inverse of the classical virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance.

| In a Dark Wood Canto 1 shows the pilgrim midway in the course of life caught in a dark wood. Canto 1 is an outline of the whole Commedia, replete with symbolism, and with classical and Scriptural allusions. Virgil is the guide we all need in the spiritual life, in this case epitomising reason. The leopard (sexual promiscuity), the lion (pride) and the she-wolf (avarice) represent temptations which confront Dante. The forest represents sin, and the darkness ignorance. 1300 is the year Dante turned 35, shortly before he was to be exiled from Florence. In effect Dante confronts the four last things – death, judgment, heaven, hell, so much part of the Christian world view. The unrepentant sinner chooses hell, rather than repudiate a good which can never satisfy. Human desire can only be satisfied by the infinite good, God. Dante summarises at the commencement of Canto 1 his spiritual state: Halfway along the road we have to go I found myself obscured in a great forest, Bewildered, and I knew I had lost the way. It is hard to say just what the forest was like, How wild and rough it was, how overpowering; even to remember it makes me afraid. Dante summarises both the fate of souls in Inferno, and the much more hopeful state of souls in Purgatorio: Where you will hear the shrieks of men without hope, And will see the ancient spirits in such pain That every one of them calls out for a second death; And then you will see those who, though in the fire, are happy because they hope they will come Wherever it may be, to join the blessed. Dante seeks Virgil’s help on the arduous journey: I said to him: ‘Poet, now by that God, Who is unknown to you, I ask your assistance: Help me to escape both this evil, and worse; Lead me now, as you have promised to do, so that I come to see St Peter’s Gate… Canto 3 shows Dante the pilgrim entering through the gates of hell. The inscription above the gates – “Abandon hope all ye who enter here” – says it all. Those Who Refuse to Make a Stand In the vestibule before the gates of Inferno are those who refused to make choices while living, who refused to take a stand, who refused to commit themselves. These sinners get what they deserve; they run after banners for all eternity. Virtuous Pagans In Canto 4 Dante meets the virtuous pagans. The only punishment here is separation from God. Dante explains the position of virtuous pagans: They have committed no sin, and if they had merits, That is not enough, for they are not baptised Which all must be, to the enter the faith which is yours. And if they have lived before the Christian era, They did not adore God as he should be adored: And I am one of those in that position. For these deficiencies, and no other fault, We are lost: There is no other penalty Than to live here without hope, but with desire. Amongst the virtuous pagans Dante nominates Saladin, the Muslim sultan and opponent of the Crusaders; the Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle; Euclid the Greek geometrician; Cicero the Roman orator; Ptolemy the Alexandrian astronomer; Hippocrates the Greek physician; Avicenna the Arabic physician and author; Averroes the Muslim physician and philosopher. |

| Descending As one descends deeper into Inferno, one finds those who have committed sins of appetite – the promiscuous, gluttons, money-grubbers and wasters, the angry and the sullen. For Dante, the sins of sensuality are not the most grievous sins. One deeper finds those who have committed sins of the intellect, sins against truth. Then deeper again, towards the centre of the earth, one finds those who have committed sins of malice – the violent, the fraudulent, the treacherous. Amongst the violent one finds tyrants, murderers, plunderers, the blasphemous – and extortionate bankers! Amongst the fraudulent are the simoniacs including Pope Nicholas III, Boniface VIII, Clement V. After the fraudulent, Dante confronts the treacherous. And finally at the very centre of the earth, Lucifer. Purgatorio In Purgatorio are found the late repentant, as well as repentant sinners whose principal fault is one of the seven deadly sins – pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, lust. |

Paradiso

Paradiso is organised around the theological virtues of faith, hope and charity, and the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance. There we meet the great Christian saints – the Blessed Virgin Mary, St Peter, St James, St John, St Benedict, St Bernard, St Francis, St Dominic, and St Bonaventure.

In Canto 10 we meet St Thomas Aquinas. At the time Dante wrote the Commedia Thomas Aquinas had not been canonised, nor had his writings received the magisterial approval they have received since. Indeed, there had been some pushback against Aquinas based on his (critical) acceptance of much of the thought of the pagan Aristotle. Typically, Aquinas introduces Dante to a whole series of others whom the Church holds in esteem – St Albert the Great, Gratian, St Isidore of Seville, the Venerable Bede, Peter Lombard, Boethius.

Mary

In the final Canto XXXIII Dante finds the Blessed Virgin Mary to whom St Bernard says:

Virgin Mother, Daughter of your Son, humble and exalted beyond any other creature

The settled end of the eternal plan,

You are she who made human nature

So noble, that the nature of it himself

Did not scorn to have himself made by it.

In your womb was lit again that love

By whose warmth, is the eternal peace, this flower has germinated as it is.

For us here you are a midday blaze

Of love; and down there, among mortals,

You are the ever living spring of hope.

Lady, you are so great, and have such power, that whoever seeks grace without recourse to you

Is like someone wanting to fly without wings

You are so benign that you not only help whoever asks you, but very often,

Spontaneously give before the prayer is made.

God

In the very last words of Canto XXXIII, Dante says in relation to the vision of God:

At this point my imagination failed;

But already my desire and my will

Were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed

By the love which moves the sun and the other stars.

| Pope Francis Pope Francis, in his Apostolic Letter Candor Lucis Aeternae: on the Seventh Centenary of the Death of Dante Alighieri (2021) explains the significance of exile and journeying in the Divina Commedia: Dante, pondering his life of exile, radical uncertainty, fragility, and constant moving from place to place, sublimated and transformed his personal experience, making it a paradigm of the human condition, viewed as a journey – spiritual and physical, that continues until it reaches its goal. Here, two fundamental themes of Dante’s entire work come to the fore, namely, that every existential journey begins with an innate desire in the human heart and that this desire attains fulfilment in the happiness bestowed by the vision of the Love who is God. Referring to Dante’s placing even popes, bishops, priests and religious in Inferno, Pope Francis comments that Dante’s prophetic mission entailed denouncing and criticising those believers who betray Christ and turn the Church into a means of advancing their own interests while ignoring the spirit of the Beatitudes and the duty of charity towards the defenceless and poor, instead idolizing power and riches. Without forming a historical judgment about Boniface VIII and the other popes whom Dante places in Inferno, Pope Francis repudiates those who would use the papacy and the Church for the achievement of worldly objectives. For the 21st century reader, not a specialist in 13th century Italian politics, it is possible to appreciate the Divina Commedia for its expression of what it means to be human, not only in 13th century Florence, but in any age. Poet of Hope According to Pope Francis, Dante is the poet of hope, nowhere more evident than amongst the repentant sinners of Purgatorio. Poet of Human Desire Dante is also the poet of human desire. In this regard, Pope Francis refers to Dante’s Convivio: The ultimate desire of every being, and the first bestowed by nature, is the desire to return to its first cause. And since God is the first cause of our souls…the soul desires first and foremost to return to him. Like a pilgrim who travels an unknown road and believes every house he sees is the hostel, and upon finding that it is not, transfers this belief to the next house he sees, and the next, and the next, until at last he arrives at the hostel, so it is with our soul. As soon as it sets out on the new and untravelled road of this life, the soul incessantly seeks its supreme good; consequently, whenever it sees something apparently good, it considers that the supreme good. Poet of God’s Mercy and Human Freedom Pope Francis regards Dante as the poet of God’s mercy and human freedom. The journey that Dante presents is within the reach of everyone, for God’s mercy always offers the possibility of change, conversion, new self-awareness, and discovery of the path to happiness. That is why Dante takes us by surprise, placing unlikely persons in both Purgatorio and Paradiso. Salvation is for everyone. Our eternal destiny, according to Pope Francis’ interpretation, depends on our free decisions. Even our ordinary and apparently insignificant actions have a meaning that transcends time: they possess an eternal dimension. The greatest of God’s gifts is the freedom that enables us to reach our ultimate goal. Freedom, Dante reminds us, is not an end unto itself; it is a condition for rising constantly higher. Image of Man in Vision of God According to Pope Francis, the interplay of freedom and desire does not diminish our humanity. At the centre of the final vision, in his encounter with the Blessed Trinity, Dante describes a human face, the face of Christ, the eternal Word made flesh in the womb of Mary. Only in the visio Dei does human desire attain fulfilment and our arduous journey come to an end. The mystery of the incarnation is the heart and inspiration of Divina Commedia. Thereby God enters history, becoming flesh, and humanity, in its flesh, is enabled to enter the realm of the divine, symbolised by Dante in the Rose of the Blessed. Our humanity is taken up into God, in whom we find our true happiness and ultimate fulfilment, the goal of all our journeying. Love Pope Francis comments, love is the sole means of our salvation, the divine love that transfigures human love. Pope Francis in Candor Lucis Aeternae is a more profound commentator on Divina Commedia than many academic writers because Pope Francis captures the theological essence of Divina Commedia. |

| Not Merely to Be Read Divina Commedia gives imaginative expression to the truth of what it is to be human, transcending and repudiating the grubby politics of 13th century Italy, a work for all time. As Pope Francis says, Dante does not wish merely to be read, commented on, studied and analysed. He asks to be heard and imitated; he invites us to become his companions on the journey. He wants to show us the route to happiness, the right path to live a fully human life, emerging from the dark forest in which we lose our bearings and the sense of our true worth. Pope Francis reminds us, Dante wants to make us appreciate fully who we are, and the meaning of our daily struggles to achieve happiness, fulfilment and our ultimate end, our true homeland, where we will be in full communion with God, infinite and eternal Love. As Dante put it: “In His will is our peace.” Michael McAuley 2 July 2021 |

Chronology: Dante Alighieri

| Date | Event |

| 1215 | Beginning of factionalism in Florence, |

| 1248-51 | First Ghibelline rule in Florence. |

| 1250 | Death of Emperor Frederick II. |

| 1260-66 | Second period of Ghibelline rule in Florence. |

| 1265 | Dante born. |

| 1266 | Guelph party dominates Florence. |

| 1274 | Death of St Thomas Aquinas. |

| 1274 | Dante – first met Beatrice. |

| 1280 | General amnesty for Ghibellines in Florence. |

| 1285 | Marriage of Dante and Gemma Donati. |

| 1290 | Dante – death of Beatrice |

| 1293-95 | Dante Vita Nuova |

| 1294-1303 | Pope Boniface VIII, whom Dante places in the eighth circle of the Inferno as a simoniac. |

| 1295 | Dante involvement in Florentine politics. |

| 1300 | Dante 35 years of age. |

| 1300 | Guelphs split between Whites and Blacks. |

| 1300 | Had to be alive no later than to be included in Divine Comedy. |

| 1301 (September) | Dante in Rome to negotiate on behalf of Florence with Boniface VIII. |

| 1301 (November) | Black Guelphs take control of Florence – expulsion of White Guelphs. |

| 1302 (January) | Dante formally condemned and exiled. |

| 1305-1314 | Francophile Pope Clement V. |

| 1307 | Arrest and imprisonment of Knights Templar in France at behest of Philip the Fair. |

| 1308-1320 | Dante – Divina Commedia |

| 1309-77 | Papacy removes from Rome to Avignon (the Babylonian exile) – originated by French Pope Clement V. |

| 1310-13 | Descent of Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII into Italy. |

| 1311-12 | Ecumenical Council of Vienne suppressors Knights Templar. |

| 1314 | Jacques of Molar, Master of Templars burnt at stake. |

| 1318-21 | Dante lives in Ravenna under patronage of Da Polenta family. |

| 1321 | Dante died – interred in Ravenna. |

| 1921 | Benedict XV. Encyclical In Praeclara Summorum |

| 2021 | Pope Francis. Apostolic Letter Candor Lucis Aeternae: on the Seventh Centenary of the Death of Dante Alighieri |