I’m sure many of you have visited the Frick Gallery in New York, where Hans Holbein’s two portraits hang on the same wall – Thomas Cromwell and Thomas More, whose execution Cromwell engineered for King Henry VIII 1535. All of the hierarchy but St John Fisher, showed the sterling lack of courage of Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean, well expressed in the terrified remark of William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury at the time: ‘the indignation of the King is death.’

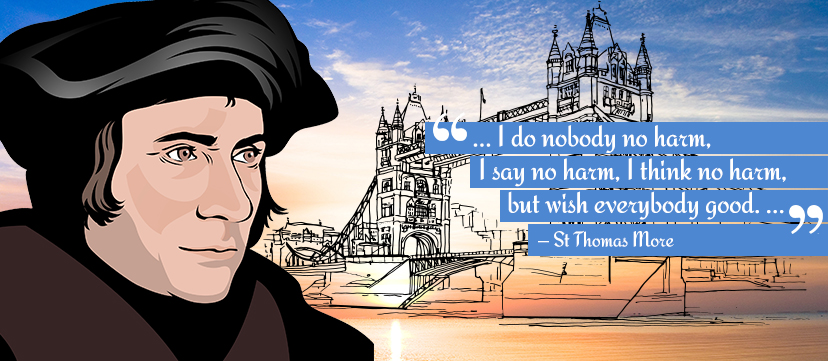

Even though as a layman, he wasn’t bound to submit as the bishops were, Sir Thomas More resigned as Lord Chancellor of England the very next day. But because More was so highly thought of, the King wanted his agreement more than anyone else’s. Still, Thomas More, as the chief law officer of England, knew the law inside out, so he resolved to say nothing. A remark he made at the time expresses his attitude:

I pray for his Highness and all the realm. I do nobody no harm, I say no harm, I think no ham, but wish everybody good. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I have long not to live.

Although he sent his greetings to Henry and his new Queen, Anne Boleyn, More angered Henry by not attending her coronation ceremony. Soon after, More was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and offered his freedom if only he would agree to what was called ‘the King’s great matter’ – that his marriage to Anne Boleyn was valid. I remember visiting his cell in the Tower some years ago – he was gradually brought almost to starvation, deprived of light and reading mater. Our guide, a burly ex-soldier in Beefeater costume, who was obviously completely puzzled by More, like a minor figure in a Shakespearean comedy said, in his Cockney accident, ‘Oi’da soigned.’

During his trial, More waited till he was convicted by perjured testimony to break his silence and give his reason for not accepting Henry’s second marriage – because it went against the law of God, entrusted to St Peter and his successors. He forgave his accusers, comparing them to St Paul, who’d stood by the clothes of those who stoned St Stephen, yet both were later united as friends forever in heaven. So he prayed that ‘we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together, to our everlasting salvation.’

Five days later, on 6 July 1535, More begged the bystanders at his execution to pray to God for him, promising he would pray for them also. Before being beheaded – as well as asking the executioner to put his beard aside as it hadn’t committed treason – he declared that he died the King’s good servant but God’s first.

St John Paul II said of him: “Precisely because of the witness he bore to the primacy of truth over power, even at the price of his life, St Thomas More is venerated as an imperishable example of moral integrity. And even outside the Church, particularly among those with responsibility for the destinies of peoples, he is acknowledged as a source of inspiration for a political system which has as its supreme goal the service of the human person.”

And during his visit to the United Kingdom in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI noted that ‘the dilemma which faced More in those difficult times, the…relationship between what is owed to Caesar and what is owed to God, led him to reflect on the proper place of religious belief within the political process.’ He found a great example of this ‘in one of the British parliament’s particularly notable achievements – the abolition of the slave trade. The campaign that led to this landmark legislation was built upon firm ethical principles, rooted in the natural law, and it has made a contribution to civilization of which this nation may be justly proud. This is why I would suggest that the world of reason and the world of faith – the world of secular rationality and the world of religious belief – need one another and should not be afraid to enter into a profound and ongoing dialogue, for the good of our civilization.’

G K Chesteron wrote in 1929, ‘Thomas More is more important at this moment than at any moment since his death, even perhaps the great moment of his dying; but he is not quite so important as he will be in about a hundred years’ time.’ We note that More didn’t die, as Bolt suggests in A Man for All Seasons, for the sovereignty of personal conscience, but for the sovereignty of Christian truth as taught by the Catholic Church, which he saw as accessible to all persons and obligating all consciences. In that, he very much remains a saint for our times.

As St John XXIII wrote in his 1963 encylical Pacem in Terris, S1: ‘Peace on earth…can never be established, never guaranteed, except by the diligent observance of the divinely established order.’ Archbishop Chaput of Philadelphia, speaking on 6 July last year, the anniversary of Thomas More’s execution, said that of these words of John XIII that:

We need to consider his words carefully. No political power can change the nature of marriage or rework the meaning of family. No lobbying campaign, no President, no lawmakers and no judges can redraw the blueprint laid down by God for the well-being of the children he loves. If men and woman want peace, there’s only one way to have it – by seeking and living the truth…We cannot care for the family by trying to redefine its meaning. We cannot provide for the family by undercutting the privileged place in our culture of a woman and a man made one flesh in marriage…It’s a good day, this July, to remember Thomas More and his witness. In the years ahead, may God give us a portion of his integrity, courage and perseverance. We’ll need it.

This homily was given by Fr Brendan Purcell on the occasion of the Feast of St Thomas More 2016.