For those of us who are working from home, despite the inconvenience and disruption, we should now have a little more time, not having to travel, and not having our usual commitments.

This is an opportunity to turn off the phone, turn off the radio, turn off the television, and turn off the computer.

The babble of constant conversation will cause us to forget the important things in life.

If we are lucky, we may be able to sit in the garden under a tree in the embracing autumnal sun, or go for a walk on a lonely path through the bush.

Great Books

Reading should always be part of our lives, but especially now.

Reading history and the classics provides us with a perspective on current events.

The American philosopher, Mortimer J Adler, in devising his Great Books programme, urged the importance of reading the classics – a relatively small number of books, from many different times and places, which are read and reread in every generation, which do not lose their significance for succeeding generations, which are often referred to and argued about by later writers of the great books so there is a continuing great conversation. These are books intended, not for specialists, but for anyone. Generally, they do not come with the paraphernalia of academia – footnotes and bibliographies. Few of them have been written by professional academics in the sense of the tenured, working in universities. The great books do not express a single opinion, but many different opinions. One great book author, in referring to others, will challenge or qualify or disagree with the opinions of others. So, the great conversation as to matters which transcend time and place and circumstance continues down the ages.

Black Death

Last year, I read about the Black Death. The Black Death, black because of its impact, began in 1346, and spent itself by 1653. In 1346 Europe had about 150 million people. Seven years later the population of Europe had halved as a result of the Black Death. The plague spread along trade routes, from east to west, eventually impacting most of Europe. Those places in Europe less impacted by international trade and travel were less impacted by the Black Death.

The Black Death had economic, social and political consequences – some became unexpectedly rich, there was a shortage of labour with increased income for many poorer people who survived, women were important participants in the workforce, populations were more concentrated in urban areas, there was greater specialisation, merchants acquired wealth which put them on par with nobles, those who exercised power before the Black Death exercised power less securely after the Black Death.

While the Black Death was spent by 1353, it recurred periodically here and there in Europe until the last major outbreak in London in 1664-67.

Wherever plague appeared, some behaved with heroism (for instance, the Franciscans and Dominicans who tended the sick and dying before dying themselves), but others abandoned reasonable social norms.

Plague of Justinian

Prior to the Black Death, in 541 the Plague of Justinian (so called after the Byzantine Emperor Justinian who caught it but survived) appeared in Byzantium. Particularly hard hit was Constantinople where 40 % of the population died. In Constantinople 10,000 people a day died. Their bodies were piled up in the streets because there was nowhere else to put them. The Plague of Justinian brought to an end Justinian’s attempts to recover the western half of what had been the Roman Empire.

In 1894 there was plague in Canton China, preceded by outbreaks sometime earlier in Yunnan province and in India. These outbreaks enabled scientists to systematically study pandemics.

Spanish Flu

The misnamed Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 infected some 500 million people worldwide, killing between 17 million and 100 million, widely different estimates.

There was an outbreak of plague in Surat India in 1994, and shortly after in Madagascar.

In the late 1990’s there was an outbreak of HIV/AIDS which, fortunately, has become more and more treatable.

SARS

In 2002-2003 the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) arose in Guangdong province of southern China, spreading to a number of countries. Fortunately, SARS has been largely contained.

In 2014-15 there was an Ebola outbreak in Africa with a mortality rate of 40%.

Reassuring is the reality that there is today a lot more scientific knowledge about epidemics and pandemics than there was at the time of the Plague of Justinian, or the Black Death. But many will die from coronavirus, many will be thrown out of work, successful businesses will fail, tenants will not be able to pay their rent, savings of a lifetime will be lost or diminished, many will be unable to face a new reality, many will engage in utterly selfish behaviour. Not a family in Australia will be untouched.

George Orwell

I have just finished a literary life of George Orwell. Some will have read Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty Four. George Orwell, aka Eric Blair, was the son of a British public servant who managed the growing of opium in India, opium sold to the Chinese, whose lives and families were destroyed by its consumption.

Great Britain fought the Opium Wars to preserve this trade, wars which provide some explanation for contemporary Chinese foreign policy.

Orwell is a critic of the abuse of power, no matter who is the abuser – bullying school teachers (Mrs Wilkes of St Cyprian’s), British imperialists (Burmese Days), capitalists (Down and Out in London and Paris, The Road to Wigan Pier), Stalinist revolutionaries (Homage to Catalonia), the misuse of language to justify the abuse of power (Politics and the English Language). Orwell is an illustration as to the inadequacy of the terms “left” and “right” (deriving from the French Revolution relating to the physical location of particular factions) for explaining differing political views. Orwell’s perspective on the abuse of power transcends the usual political categories. What Orwell is about is the abuse of power which is confined to neither “left” nor “right”.

Dante

On holidays I keep beside my bed Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy. Dante is the greatest of Italian writers, placing before the reader the vices that are hell, the hope that is purgatory, the glory that is heaven. The Inferno is the most read part of the trilogy, with sinners receiving a punishment uniquely suited to their predominant vice. If Dante had been writing today where would be some of our contemporaries? some of our leaders? us?

Socrates

Socrates is the thinker who wrote nothing, but asked questions, disturbing the self-satisfied conformist complacency of the Athenians, challenging the “gods” of Athens, condemned to death following a trial by jury, inspiring the dialogues of Plato.

Socrates established an intellectual method, which involves never being afraid to ask a question, putting the argument of one’s intellectual opponent as fairly, as forcefully, and as persuasively as possible, and then answering that argument.

Socrates’ contribution to ethics is his awareness that, in performing this or that act, we become that act. So while our actions impact on others, on things beyond us, our actions make us the person we are. Thus, when we do wrong, when we do evil, the person we most damage, the person we most injure is ourself. We become what we do.

Plato’s account of the last days of Socrates is never to be forgotten – the trial (Apology), prison (Crito), death (Phaedo). Socrates, in addressing the jury which condemned him, says:

You too, gentlemen of the jury, must look forward to death with confidence, and fix your minds on this one belief, which is certain: that nothing can harm a good man either in life or after death…For my part I bear no grudge at all against those who condemned me and accused me…However, I ask them to grant me one favour. When my sons grow up, gentlemen, if you think they are putting money or anything else before goodness, take your revenge by plaguing them as I plagued you; and if they fancy themselves for no reason, you must scold them just as I scolded you, for neglecting the important things and thinking they are good for something when they are good for nothing.

Tuckiar

In the dusty volumes of the Commonwealth Law Reports is Tuckiar’s Case, arguably the most important case in the collection, dealing with the duty of an advocate to his client, in this case an Aborigine who spoke no English, with no adequate interpreter, stitched up by the police on a charge of murder, with an overbearing judge, and vengeful public opinion. An advocate must be fearless, willing to stand up for his or her client, even at the risk of unpopularity and judicial anger. Each and every person, no matter who, is entitled to justice, and courageous advocacy.

Big Questions

Reading history and the classics – reading the history of the Black Death, George Orwell, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Socrates, Tuckiar – will introduce us to other times and places, will open to us people and perspectives we meet but mutely in daily life, will prompt us to think about the big questions.

Easter

We are now approaching Easter. We could focus on the suffering and death of Jesus Christ, knowing that suffering is part of every life, that, much as we run away from suffering, it will always catch up with us, will always confront us. The gospel accounts are an answer to the question of suffering, asked but not satisfactorily answered in Job, and in the Deuteronomistic tradition (which sees suffering as retribution for a person’s wrong doing).

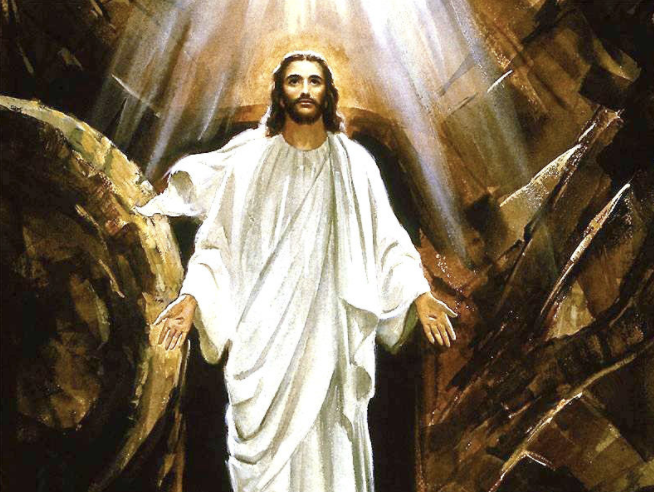

Resurrection

But part of the account of the life of Christ is the resurrection, something which some “scholars” interpret as non-historical accretion, as fiction, as myth.

But that is not the account of St Paul whose writings about Christ are first in time, nor the account of the gospel writers who wrote after St Paul, but drawing on an older oral tradition, and on a document or documents which have been lost. Only faith will accept the resurrection, and the significance of the resurrection.

Josephus

What the early Christians believed, what is distinctive about Christian thought at the beginning, is that Jesus rose from the dead. This is what the first century Jewish historian Josephus says of the Christians. Indeed, Josephus says more:

Now, there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, but he was a doer of wonderful works-a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was the Christ, and when Pilate at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had told these and ten thousand wonderful things about him; and the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct to this day.

If one accepts the account of St Paul, and of the Gospels, if one accepts the action of a loving God intervening in human history, particularly in the history of the Jews, one accepts the historicity of the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

St Peter

St Peter, in a dense passage, too long to fully quote here, requiring a lifetime to unpack, explains the significance of the resurrection:

For it is better to suffer for doing right, if that should be God’s will, than for doing wrong. For Christ also died for our sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but alive in the spirit…Baptism…now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a clear conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers subject to him. (Peter 3:18-22)

Catechism

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, an authoritative document, destined, after the Bible, to become one of the most read books of all time, unpacks the meaning and significance of the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

As St Paul said, if Christ had not been raised, his preaching is in vain, and our faith is in vain. The resurrection constitutes confirmation of all Christ’s works and teachings. Christ’s resurrection confirms his divine authority. Christ’s resurrection is the fulfilment of the promises of scripture, and of the promises of Jesus during his earthly life. The truth of Christ’s divinity is confirmed by his resurrection; the resurrection shows that Christ is the I AM, the Son of God and God himself. By his death Christ liberates us from sin, and by his resurrection opens for us the way to a new life. Christ’s resurrection-and the risen Christ himself-is the principle and source of our future resurrection.

Jesus Christ – who lived in what is modern Palestine, modern Israel-was crucified under Pontius Pilate, died and was buried-and rose again on the third day. This is our faith, this is our hope.

Michael McAuley