During the Pol Pot period in Cambodia from 1975-1978, some two million people were killed, some because they wore glasses, some because they were Buddhist, some because they were teachers or doctors, or shop-keepers, some because they were said to be enemies of the regime, some for no reason at all. The goal was to create a new society by killing people.

Comrade Duch (who died earlier this year) who ran the S 21 facility in a former high school in the capital, Phnom Penh, was responsible for the torture and murder of untold numbers of Cambodians. Comrade Duch justified his actions on the basis that his superiors gave orders which he was bound to obey. Comrade Duch faithfully repeated the slogans “Our party makes absolutely no mistakes” and “Angkor knows who is good and who is bad”. Should we “respect” Comrade Duch’s actions or should we condemn them?

US Bombing

Immediately before the Pol Pot period, the US bombed the Ho Chi Minh trail, the long narrow corridor inside Cambodia from what was North Vietnam to South Vietnam, down which Viet Cong supplies were brought. The bombing killed some 500,000 Cambodian civilians. What are we to make of this? Was this killing distinguishable from the killing which later occurred during the Pol Pot period?

Landmines

Even today, there are believed to be some 4-6 million landmines in Cambodia. There are some 40,000 amputees who have lost limbs because of placement of landmines in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Landmines are indiscriminate in who they kill and maim long after hostilities are ended.

The experience of Cambodia in the 1970’s and 1980’s raises issues as to whether there are standards of human conduct which oblige us, regardless of time, place and circumstance.

What is Good For Us

We know that we need to eat and drink what is good for us; exercise sufficiently; get enough sleep; dress appropriately according to the time of day, and the weather; get on with our friends, and neighbours, and colleagues; know the truth about things, appreciate beauty – a sunset, a sculpture, a painting, a well-played game of football, a smile on the face of a child.

We know that we flourish in our relationship with others; we depend on others, and they depend on us. We know what is good for us – and what is good for each other. We expect spouses to care for each other; parents to care for their children; children to care for their parents in their old age; employers to pay their employees appropriately, and not expose their employees to unsafe working conditions; employees to pull their weight; witnesses to tell the truth in court; politicians to care for the common good; citizens to obey the law, pay their taxes, and, if necessary, defend their country when invaded unjustly.

We honour those who contribute to the common good – firefighters, police, nurses, doctors, teachers, scientists, entrepreneurs, statesmen, writers, composers, and sporting heroes. And we denounce the actions of those who damage the common good – corrupt politicians, demagogues, crooked salesmen, corporate shysters, confidence tricksters, peddlers of lies, tyrants, paedophiles, company directors who destroy the environment in search of profits, mass murderers, drug-dealers, slave-dealers, thieves, war-mongers, choleric judges who play favourites, hubristic purveyors of double standards who consider there is one easy law for themselves and another tougher law for everyone else.

Treating others as we would wish to be treated

We understand that we ought to treat others as we would wish to be treated. If we are honest with ourselves, we admit that we often do not adhere to the standards of behaviour we set ourselves, sometimes in big matters, sometimes in small matters.

Human Virtue

We realise there are human virtues – prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance and so on – which we fulfil to a greater or lesser extent. We also recognise that there are some who reject the standards of behaviour commonly accepted as binding on everybody, some for intellectual reasons, some thoughtlessly as a matter of practice.

Wrongdoing

In many cases, we have such entrenched habits of wrongdoing we do not recognise the evil we do (the perennially angry spouse, the drunk, the social media addict, the workaholic, the parent who fails to spend time with his or her children, the person so intent on a hobby he or she ignores the needs of others, the gossip, the person forever critical of the motives and deeds of others, the person who lacks the energy to do things, the person who never takes a risk, the person who is incapable of generosity with either money or time, the person who has all sorts of imaginary illnesses).

In many cases, we are so entrenched in the surrounding culture we do not recognise evil which is commonly accepted in that culture (the guard in the Nazi death camp, the Roman attending gladiatorial contests, the media addict forever watching violent and pornographic movies, the soldier who murders civilians, the person forever buying chocolates whenever they happen to purchase petrol, the person who sees others persistently doing wrong but never says anything, however kindly). In many cases, we are so inflamed by passion we do not know what we are doing is wrong (the Don Juan intent on sexual conquest, the company director intent on profits dependent on a supply chain deriving from slave labour, the corporate executive who always puts the profit bottom line before people, the person who puts career before family, the politician adept at putting corporate interests before the common good).

In many cases, we are forever selfish (the person who never helps the needy, who never thinks of others, who never forgives, who never overlooks a wrong, who is always right, who lacks basic manners, who can never give way in a dispute, who is always concerned to “look” good).

What I Do or Fail to Do

If I have even minimal insight, I recognise that there is not a day in which I do not do wrong in what I do, in what I fail to do. Wrong-doing is not what other people do, nor fail to do. It is what I do and what I fail to do.

The fact that wrong-doing is so common does not mean there is no right and wrong, no good and evil. Mathematical errors occur. Historical events are misunderstood. The nature of physical reality is so far from what our senses tell us, and what common sense would have us believe (the earth seems broadly flat, but is, in fact, spherical, travelling around the sun). Popular opinions (astrology, medical quackery, support for corrupt and dishonest politicians, mindless listening to air-headed shock jocks, inane adoption of ideologies derived from a very incomplete understanding of reality) are far from the truth. So much culture is tasteless, even false. That does not mean there do not exist truth and beauty. The prevalence of evil does not mean there is no good.

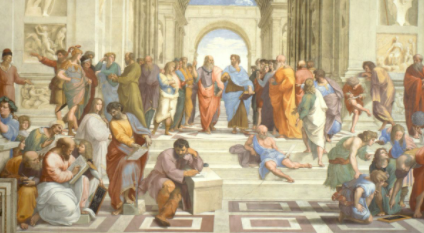

Ancient Greeks

This understanding, that there are perennial standards of good and evil, right and wrong, was a commonplace in ancient Greece. Aristotle distinguishes between the law of this or that place, and laws which are perennially valid. Similarly, the Stoics had an understanding of what has become known as natural law. The Romans, to a great extent, adopted the superior culture of the Greeks. Shortly before St Paul, the Roman statesman and advocate, Marcus Tullius Cicero, was an advocate for a perennial understanding of human good.

St Paul

St Paul was born in Tarsus, a city of about a quarter of a million people in Cilicia (modern Turkey), a member of the Jewish diaspora spread through much of the then known world. St Paul was martyred in Rome in the 60’s. Greek was probably St Paul’s first language, although his letters demonstrate a thorough knowledge of what became the Hebrew Bible. St Paul probably was comfortable with the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible read by the Jews of the diaspora. St Paul was exposed from his youth to Greco-Roman literature and philosophy. He was also trained in the pharisaic tradition in Jerusalem. So, it is not humanly surprising (albeit we see in what St Paul writes, the inspired word of God) that St Paul says:

“When the Gentiles who have not the law do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even they do not have the law. They show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness and their conflicting thoughts accuse or perhaps excuse them on that day when, according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus” (Romans 2:14-16).

Wisdom

The synthesis of Greek and Jewish thought is nowhere more evident than in the Book of Wisdom, written shortly before Christ. The virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance have their origins in the thought of the Greeks and are assumed by the Hebrews (Wisdom 8:7). St Paul, in picking up the Greek notion of what has been called natural law, illustrates the tradition of adopting the true and the good and the beautiful, wherever it is to be found.

Natural Law

What is the meaning of the strange term “natural law”? It is that as humans (like other beings) we have a whatness, an essence, a nature, that determines what is good for us. Aristotle called that human nature “rational animal” – a useful summary of what we are. Having a human nature, we have an immense number of possibilities open to us. But some things are good for us, for our happiness, and some things are not good for us. Hence when we do evil, the person we most harm is ourself.

St Thomas Aquinas

What St Thomas Aquinas brings to the tradition of reflection about human action is a synthesis of the best of thought that precedes him, together with a seminal quality which infects and helps flourish thought that succeeded him. So if one goes to the Summa Theologiae, which one must do if one is to be an educated person, Aquinas’ Treatises on Law, on Justice and on Injustice, have a timeless quality which demands our reading even today. Aquinas’ definition of law, as “a rule of reason, promulgated for the common good by whoever has charge of the community,” possesses a wisdom which can be applied at all times, in all places, all circumstances. Similarly, with Aquinas’ first principle of human action – good is to be done and pursued, evil to be avoided.

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891) applies Thomistic thought to the then new circumstances of the shift from an agrarian economy to an industrial economy, urging minimum wages sufficient to support a family, regulation of working conditions to protect the health and safety of workers, recognition of the right of workers to organise in unions to enable collective bargaining as to employment condition. The law of the market is to be regulated by the law of the state for the good of workers and their families. With Leo XIII begins the tradition of social justice encyclicals, a tradition which was influential in the fledgling Australian Labor Party in the 1890’s and at the beginning of the 20th century.

Pope St John XXIII

As part of the tradition of natural law thinking, Pope St John XXIII in Pacem in Terris (1961) considers human rights, thought by some to be an 18th century invention, but which can be traced, at least implicitly, to the Galilean himself. Pope St John XXIII in Mater et Magistra (1963) considers less economically developed, or third world, countries. Pope St John Paul II in Veritatis Splendor (1983) restated this tradition in the first encyclical ever devoted to Catholic moral theology.

John Finnis

The tradition of thinking about human action, appealing to standards of good and evil, right and wrong, which transcend time, place and circumstance has many different adherents. It is difficult to discuss what should be done here and now, in this or that situation, without appealing to objective standards which transcend time and place and circumstance. Significant here is John Finnis, the lawyer from South Australia who, in 1980, first published Natural Law and Natural Rights. John Finnis is one of the most significant living jurisprudential thinkers in the Anglo-American world.

The natural law tradition of human thought provides an answer to Comrade Duch, the Superintendent of S21 in Phnom Penh, an answer to the US architects of the bombing of 500,000 Cambodians who lived along the Ho Chi Minh trail, and an answer to those who laid landmines throughout Cambodia, landmines which kill and injure Cambodians, even today.

Michael McAuley