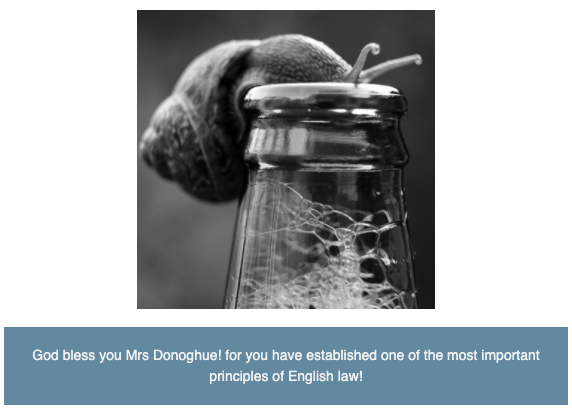

It started on 26 August 1928 with a trip to the Wellmeadow Cafe in Paisley, near Glasgow where Mrs Donoghue’s friend shouted Mrs Donoghue a Scotsman’s float- ice-cream and a bottle of ginger beer. The bottle was opaque. Mrs Donoghue drank some of the ginger beer.

Snail in Ginger Beer Bottle

When Mrs Donoghue was refilling her glass, a partly decomposed snail floated out of the bottle! Mrs Donoghue was shocked and suffered a severe attack of gastroenteritis requiring medical attention. Proceedings were brought against Stevenson, the manufacturer, but not against the Wellmeadow Cafe, as the bottle was opaque, and the Wellmeadow Cafe had no possibility of examining the bottle’s contents. The writ commencing proceedings alleged Stevenson’s plant was a place where snails and the slimy trails of snails were frequently found!

House of Lords

On a preliminary point as to whether the action by Mrs Donoghue was maintainable, the case ended up for argument on 10 and 11 December 1931 in the House of Lords. In order to get to the House of Lords without putting up security for costs Mrs Donoghue had to demonstrate her impecuniosity. Mrs Donoghue swore in an affidavit: “I am very poor. I am not worth five pounds in all the world.” Evidence confirming Mrs Donoghue’s poverty came from the minister and two elders of her church. It would seem Mrs Donoghue’s lawyers specked her case.

The House of Lords handed down a decision on 26 May 1932, 3/2 in Mrs Donoghue’s favour. The House of Lords found the action by Mrs Donoghue was maintainable. So, Mrs Donoghue was the successful party. Eventually, matter was settled prior to hearing for £200. Some malicious gossips later suggested there was no snail in the ginger beer bottle! This was untrue.

Lord Atkin

God bless you Lord Atkin! for you recognised and enunciated the principle of law in Donoghue v Stevenson, drawing on the old Gospel story of the Good Samaritan!

In his lead decision in Donoghue v Stevenson, Lord Atkin said:

At present I content myself with pointing out that in English law there must be, and is, some general conception of relations, giving rise to a duty of care, of which the particular cases found in the books are but instances. The liability for negligence, whether you style it such or treat it as in other systems as a species of “culpa”, is no doubt based upon a general sentiment of wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. But acts or omissions which any moral code would censure cannot, in a practical world, be treated so as to give a right to every person injured by them to demand relief. In this way rules of law arise which limit the range of complainants, and the extent of their remedy. The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer’s question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be – persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.

Rationale for Coherence of Law

Donoghue v Stevenson is, arguably, the most important court decision in the common law world. In any given year there are millions of cases in some way dependent on the law as stated by Lord Atkin. Proximity is no longer the concept it was in Australia. However, Lord Atkin’s statement of the law has been remarkably successful in supplying a touchstone for coherence in the law of negligence, rationalising the concept of duty of care, whilst providing from incremental development of the law.

Pope Francis

God bless you Pope Francis! for in the encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: on Fraternity and Social Friendship, you have taken the old Gospel story of the Good Samaritan and given it flesh in the 21st century!

In Fratelli Tutti we have the heart of Pope Francis’ thought, the third of Pope Francis’ encyclicals. This is no easy read. Many themes of the tradition are brought together in the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2004). Fratelli Tutti is to be read as a development of this tradition of Catholic Social Teaching. Fratelli Tutti cannot be read apart from the tradition.

Good Samaritan

The account of the Good Samaritan in St Luke’s Gospel is a commonplace of western thought, urging love of God above all, and love of one’s neighbour as oneself. The lawyer’s question – Who is my neighbour? – elicits Christ’s parable of the Good Samaritan. The one was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of robbers was the one who showed him mercy. The journey from Jerusalem to Jericho is 17 miles, descending 3,200 feet, the rough terrain making the road a lurking place for thieves and robbers. The priest and the Levite could reasonably have feared for their own safety. Each would have wished, in accordance with the proscription of Leviticus, to avoid touching the corpse of someone, not a family member, so as to avoid ritual impurity.

A few years ago, while visiting the Holy Land, I looked from the mountains surrounding Jerusalem down the still lonely road which descends to Jericho. I could well understand a certain caution about approaching a body lying on the side of the lonely road. So, one might understand the reluctance of the priest and Levite to get involved. The Samaritan gave the innkeeper two denarii, about two days wages, which would have paid for several days’ accommodation. Referring to the Good Samaritan, Christ (and Pope Francis) says, Go and do likewise. The impact of the parable of the Good Samaritan on western culture is exemplified by the many artistic representations, including by Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

The Samaritan

The Samaritans lived in the Holy Land at the time of Jesus of Nazareth. They were descendants of Jews who had intermarried with the invaders at the time of the Assyrian invasion of the northern kingdom in the eighth century. They practised a syncretist religion, partly derived from Judaism, and partly derived from paganism. The Samaritans had their Temple, not in Jerusalem, but at Mt Gerizim. The Jews had contempt for the Samaritans, and avoided contact with them.

Universal Parable

Christ’s story of the Good Samaritan bears a weight of meaning which is incapable of brief expression, except in parable form. It is easy for anyone to understand. It is both near and far. It is now a common place of our culture. Yet, it expresses a practical truth which transcends place and circumstance. Although just a story, it is a story for everyone, for all times, all places, all circumstances.

Scriptural Context

Pope Francis situates the parable of the Good Samaritan in the context of what Jews call the Hebrew Bible. In Tobit we are commanded, Do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you. Referring to Tobit, in the first century before Christ, Rabbi Hillel stated: This is the entire Torah, everything else is commentary.

Migration

Chapter 4 of Fratelli Tutti is concerned with migration, perhaps the most controversial chapter of the encyclical, challenging citizens of first world countries uneasy, or even hostile, at migration by persons from the third world. According to Pope Francis, complex changes arise when our neighbour happens to be an immigrant. Ideally, unnecessary migration ought to be avoided; this entails creating in countries of origin the conditions needed for a dignified life and integral development. Yet until substantial progress is made in achieving this goal, we are obliged to respect the right of all individuals to find a place that meets their basic needs and those of their families, and where they can find personal fulfilment. Our response to the arrival of migrating persons can be summarized by four words: welcome, protect, promote and integrate.

Individualism

If one wishes to express in a word what Pope Francis is against, it is individualism-or, in a phrase, Everyone for himself. We are social beings who grow and flourish in our relations with each other. We need each other.

Kindness

Pope Francis urges kindness, speaking words of comfort, strength, consolation and encouragement to each other – not words that demean, sadden, anger or show scorn. Pope Francis urges we take time to stop and be kind to others, saying, Excuse me, Pardon me, Thank You.

Forgiveness

Pope Francis urges forgiveness. Adopting his consistently scriptural approach, Pope Francis urges us to forgive seventy times seven, to admonish our opponents with gentleness, to speak evil of no one, to avoid quarrelling, to be gentle, to show every courtesy to everyone, not to fuel anger, to avoid enmities and hatred.

Lofty Vocation of Politics

Pope Francis refers to the lofty vocation of politics motivated by charity and directed to the common good. Thus, if someone helps an elderly person cross a river, that is a fine act of charity. The politician, on the other hand, builds a bridge, and that too is an act of charity. While one person can help another person by providing something to eat, the politician creates a job for that other person, and thus practices a lofty form of charity that ennobles his or her political activity.

Francis urges a preferential love for those in greatest need – reiterating Catholic Social Teaching on solidarity directed to the common good, and subsidiarity directed to the person, the family, and community groups. In this context, everything must be done to protect and respect both human dignity, and human rights, for instance, as regards elimination of hunger, human trafficking and slave labour.

Open to Everyone

We must be open to everyone. We must unite, not divide. Politicians must practice love, indeed tenderness, towards the smallest, the weakest, the poorest, in their daily interpersonal relationships. Politics is not about ambition, a quest for power, but about love. Thus, Francis rejects posturing, marketing and media spin. These sow nothing but division, conflict and cynicism. It is in this context that Pope Francis provides a very insightful analysis, and rejection, both of contemporary populism and liberalism, of relevance, not only to politicians, but to all.

Political Manipulation

Pope Francis rejects political manipulation. According to Pope Francis, the best way to dominate and gain control over people is to spread despair and discouragement, even under the guise of defending certain values. Today, in many countries, hyperbole, extremism and polarization have become political tools. Employing a strategy of ridicule, suspicion and relentless criticism, in a variety of ways, one denies the right of others to exist or to have an opinion. Their share of the truth and their values are rejected and, as a result, the life of society is impoverished and subjected to the hubris of the powerful. Political life no longer has to do with healthy debates about long-term plans to improve people’s lives and to advance the common good, but only with slick marketing techniques primarily aimed at discrediting others. In this craven exchange of charges and counter-charges, debate degenerates into a permanent state of disagreement and confrontation.

Media

Pope Francis states that dialogue is often confused with something quite different: the feverish exchange of opinions on social networks, frequently based on media information that is not always reliable. These exchanges are merely parallel monologues. Monologues engage no one, and their content is frequently self-serving and contradictory. The media’s noisy potpourri of facts and opinions is often an obstacle to dialogue, since it lets everyone cling stubbornly to his or her own ideas, interests and choices, with the excuse that everyone else is wrong. It becomes easier to discredit and insult opponents from the outset than to open a respectful dialogue aimed at achieving agreement on a deeper level. Worse, this kind of language, has become so widespread as to be part of daily conversation. Discussion is often manipulated by powerful special interests that seek to tilt public opinion in their favour. People are concerned not for the common good, but for the benefits of power or, at best, for ways to impose their own ideas.

Treating Others as Family

Working to overcome our divisions without losing our identity as individuals presumes that a basic sense of belonging is present in everyone. Indeed, society benefits when each person and social group feels truly at home. In a family, parents, grandparents and children all feel at home; no one is excluded. If someone has a problem, even a serious one, even if he brought it upon himself, the rest of the family comes to his assistance; they support him. His problems are theirs. In families, everyone contributes to the common purpose; everyone works for the common good, not denying each person’s individuality but encouraging and supporting it. They may quarrel, but there is something that does not change: the family bond. Family disputes are always resolved afterwards. The joys and sorrows of each of its members are felt by all. That is what it means to be a family! If only we could view our political opponents or neighbours in the same way that we view our children or our spouse, mother or father! How good would this be! Do we love our society or is it still something remote, something anonymous that does not involve us, something to which we are not committed?

We Are All Called to be Good Samaritans

Each of us, in our way, should be concerned for the common good which includes concern for the poorest and most vulnerable, concern to unite, not divide. We are all called to be Good Samaritans. We should not cross to the other side of the road. In this context Pope Francis is part of the personalistic tradition which acknowledges the worth of every human person, always and everywhere.

There is much more in Fratelli Tutti – social media, diplomacy, historical injustices, negotiation, demonstrations, the social obligations associated with property ownership, pluralism, the importance of the United Nations, and of international law, war, capital punishment, religious fundamentalism.

Fratelli Tutti is a statement of Catholic Social Teaching of great subtlety and depth which cannot be adequately summed up here. It demands reading and rereading, and reference to other writings in the intellectual tradition of which it is part, as well as discussion by different persons who will bring to it different perspectives.

Always Relevant, Always True

The parable of the Good Samaritan continues to be relevant to the law, as Lord Atkin draws from it a timeless rule as to our responsibility for the impact of our actions on others. The parable of the Good Samaritan continues to be relevant to life in the 21st century, as Pope Francis draws from it principles about how we should live. The parable of the Good Samaritan is always relevant, always true-and Mrs Donoghue deserves a statue in every courthouse, as having established the neighbour principle!

Michael McAuley